What this really means is that the classical elements are familiar

representatives of the different physical states that matter can

adopt. Earth represents not just soil or rock, but all solids. Water is

the archetype of all liquids; air, of all gases and vapours. Fire is a

strange one, for it is indeed a unique and striking phenomenon.

Fire is actually a dancing plasma of molecules and molecular

fragments, excited into a glowing state by heat. It is not a substance

as such, but a variable combination of substances in a particular

and unusual state caused by a chemical reaction. In experiential

terms, fire is a perfect symbol of that other, intangible aspect of

reality: light.

The ancients saw things this way too: that elements were types, not

to be too closely identified with particular substances. When Plato

speaks of water the element, he does not mean the same thing as

the water that flows in rivers. River water is a manifestation of

elementary water, but so is molten lead. Elementary water is ‘that

which flows’. Likewise, elementary earth is not just the stuff in the

ground, but flesh, wood, metal.

I was first recently made aware of this interpretation before. It really makes the theory much more plausible and makes it more believable that bright people believed this to be true.

–

Lavoisier’s belief reveals that he still held a somewhat traditional

view of elements. They were generally regarded as being rather like

colours or spices, having intrinsic properties that remain evident in

a mixture. But this is not so. A single element can exhibit very

different characteristics depending on what it is combined with.

Chlorine is a corrosive, poisonous gas; combined with sodium in

table salt, it is completely harmless. Carbon, oxygen, and

nitrogen are the stuff of life, but carbon monoxide and cyanide

(a combination of carbon and nitrogen) are deadly. This was a hard

notion for chemists to accept. Lavoisier himself came under attack

for claiming that water was composed of oxygen and hydrogen: for

water puts out fires (it is ‘the most powerful antiphlogistic we

possess’, according to one critic), whereas hydrogen is hideously

flammable.

An early example of the fallacy of division/composition.

–

Thus there is nothing optimal or ideal about living on an oxygen-

rich planet; it is simply the way things turned out. Oxygen is, after

all, an extremely abundant element: the third most abundant in

the universe, and the most abundant (47 per cent of the total) in

the Earth’s crust. On the other hand, the living world (the

biosphere) has contrived to maintain the proportion of oxygen in

the atmosphere at more or less the perfect level for aerobic

(oxygen-breathing) organisms like us. If there was less than 17

per cent oxygen in the air, we would be asphyxiated. If there was

more than 25 per cent, all organic matter would be highly

flammable: it would combust at the slightest provocation, and

wildfires would be uncontrollable. A concentration of 35 per cent

oxygen would have been enough to destroy most life on Earth in

global fires in the past. (NASA switched to using normal air

rather than pure oxygen in their spacecrafts for this reason, after

the tragic and fatal conflagration during the first Apollo tests in

1967.) So the current proportion of 21 per cent achieves a good

compromise.

This constancy of the oxygen concentration in air lends support to

the hypothesis that the biological and geological systems of the

Earth conspire to adjust the atmosphere and environment so that

they are well suited to sustain life – the so-called Gaia hypothesis.

Oxygen levels have fluctuated since the air became oxygen rich, but

not by much. In addition, today’s proportion of atmospheric oxygen

is large enough to support the formation of the ozone layer in the

stratosphere, which protects life from the worst of the sun’s harmful

ultraviolet rays. Ozone is a UV-absorbing form of pure oxygen in

which the atoms are joined not in pairs, as in oxygen gas, but in

triplets.

This smells like the ‘backwards’ thinking that fuels the arguments from design. The reason that the oxygen level is ‘just right’ for organisms, is that.. they have evolved to fit the current (or recent ancestral) levels of oxygen in the air.

Also, the claims sound rather fishy, and i cudn’t either confirm or disconfirm when i tried with Wikipedia and Google.

–

And the crowning irony is that gold is the most useless of metals,

prized like a fashion model for its ability to look beautiful and do

nothing. Unlike metals such as iron, copper, magnesium,

manganese, and nickel, gold has no natural biological role. It is too

soft for making tools; it is inconveniently heavy. And yet people

have searched for it tirelessly, they have burrowed and blasted

through the earth and sifted through mountains of gravel to claim

an estimated 100,000 tonnes in the past five hundred years alone.

‘Gold’, says Jacob Bronowski, ‘is the universal prize in all countries,

in all cultures, in all ages.’

That doesn’t seem right to me. The symbolism section on Wikipedia seems to be pretty much only about indo-european cultures, and no data about, say, pre-contact African cultures. However, after my quick googling around, i didn’t find any more data about this.

–

The metals are the most familiar and recognizable of the chemical

elements to non-scientists – for everyone senses the uniqueness of

stolid iron, soft and ruddy copper, mercury’s liquid mirror. And

among these ponderous substances no element has more resonance

and rich associations than gold. It is an enduring symbol of

eminence and purity. The best athletes win gold metals (in a trio of

metals that echoes that of the oldest coinage); the best rock bands

win golden discs. A band of gold seals the wedding vows, and fifty

years later the metal valorizes the most exalted anniversary of

married bliss. Associations of gold sell everything from credit cards

to coffee. Platinum is rarer and more expensive, and some attempts

have been made to give it even grander status than gold. But it will

not work, because there are no legends or myths to support it. There

can be no other element than gold whose chemical characteristics

have been so responsible for lodging it firmly in our cultural

traditions.

Yes, they do. I have seen many such examples. The first three that came to mind are: 1) In Crash Bandicoot games, the player is rewarded with a platinum relic which is better than the gold relic (random video of this), 2) In Starcraft 2, the Platinum league is higher (better) than the Gold league, 3) in music sales classification, platinum is better than gold. I’m sure that there are tons of more examples.

–

So how many elements are there? I do not know, and neither does

anyone else. Oh, they can tell you how many natural elements there

are – how many we can expect to find at large in the universe. That

series stops around uranium, element number 92.* But as to how

many elements are possible – well, name a number. We have no idea

what the limit might be.

* Elements slightly heavier than uranium, produced by radioactive decay (see

later), are found in tiny amounts in natural uranium ores. Plutonium (element 94)

has also been found in nature, a product of the element-forming processes that

happen in dying stars. So it is a tricky matter to put a precise number on the

natural elements.

I thought that only atoms up to Uranium were natural, but apparently not. Wikipedia lists 98 elements that are currently known to occur naturally, either on Earth or in some distant star. I had also conflated natural elements with elements that have at least one stable isotope. However, on reflection i see that i was just wrong, since Radon (Rn) occurs naturally but doesn’t have a stable isotope. There are a few other natural elements that also lack a stable isotope (as far as we know, anyway).

–

Polar ice contains tiny bubbles of trapped ancient air, within which

scientists can measure the amounts of minor (‘trace’) gases such as

carbon dioxide and methane. These are greenhouse gases, which

warm the planet by absorbing heat radiated from the Earth’s

surface. The ice cores show that levels of greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere, controlled in the past by natural processes such as

plant growth on land and in the sea, have risen and fallen in near-

perfect synchrony with temperature changes. This provides strong

evidence that the greenhouse effect regulates the Earth’s climate,

and helps us to anticipate the magnitude of the changes we might

expect by adding further greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

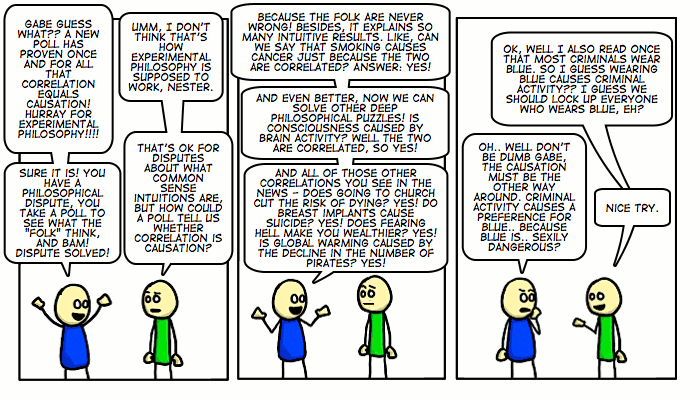

No it doesn’t. The causal relation cud be some entirely other way. He might be right, but simply reasoning like that is a causal reasoning fallacy. Also, for good fun, here are two funnies:

–

An isotope of the rare element technetium, denoted 99mTc, is widely

used to form images of the heart, brain, lungs, spleen, and other

organs. Here the ‘m’ indicates that the isotope, formed by decay of a

radioactive molybdenum isotope created by bombardment with

neutrons, is ‘metastable’, meaning only transiently stable. It decays

to ‘normal’ “Tc by emitting two gamma rays, with a half-life of six

hours. This is a nuclear process that does not change either the

atomic number or the atomic mass of the nucleus – it just sheds

some excess energy.

As a compound of 99mTc spreads through the body, the gamma

radiation produces an image of where the radioisotope has travelled.

Because the two gamma rays are emitted simultaneously and in

different directions, their paths can be traced back to locate the

emitting atom precisely at the point of crossing. This enables three-

dimensional images of organs to be constructed (Fig. 16). Scientists

are devising new technetium compounds that remain localized in

specific organs. Eventually, the technetium is simply excreted in urine

This is cool. Never heard of metastable isotopes before.

–