Philosophers seem particularly apt at coming up with bad ideas. Maybe this is just because they are so good at coming up with ideas in general. If we assume that most currently accepted ideas are generally not totally crazy, then deviating from this norm is likely to lead astray no matter how much (this is the topic of Joseph Henrich’s Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution). The best recentish book on this topic that I’ve read is Croat philosopher Neven Sesardić’s When Reason Goes on Holiday: Philosophers in Politics (2016):

Philosophers usually emphasize the importance of logic, clarity and reason. Therefore when they address political issues they will usually inject a dose of rationality in these discussions, right?

Wrong. This book gives a lot of examples showing the unexpected level of political irrationality among leading contemporary philosophers. The body of the book presents a detailed analysis of extreme leftist views of a number of famous philosophers and their occasional descent into apology for—and occasionally even active participation in—totalitarian politics. Most of these episodes are either virtually unknown (even inside the philosophical community) or have received very little attention.

The author tries to explain how it was possible that so many luminaries of twentieth-century philosophy, who invoked reason and exhibited rigor and careful thinking in their professional work, succumbed to irrationality and ended up supporting some of the most murderous political regimes and ideologies. The huge leftist bias in contemporary philosophy and its persistence over the years is certainly a factor but it is far from being the whole story.

Interestingly, the indisputably high intelligence of these philosophers did not actually protect them from descending into political insanity. It is argued that, on the contrary, both their brilliance and the high esteem they enjoyed in the profession only made them more self-confident and less cautious, thereby eventually making them blind to their betrayal of reason and the monstrosity of the causes they defended.

When I was a philosophy student back in 2010-2012, I also noted that people who were into continental philosophy seemed to be more left-wing and into general mumbo-jumbo than those who liked logic and science, the analytic school, also known as Anglo-Saxon philosophy. Sure enough almost all the famous French pseudodeep thinkers are far-left, whether structuralism, postmodernism or the latest rebranding of Marxism. Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont famously wrote a book about this Fashionable Nonsense back in 1996 after they had hoaxed them into printing some deliberately gibberish paper. And even their book is still left-wing. But is there anything to this idea that a focus on logic associates with non-socialism?

Well, 2 years ago, there was a big survey of philosophers that asked about politics and specialty:

-

Peters, U., Honeycutt, N., De Block, A., & Jussim, L. (2020). Ideological diversity, hostility, and discrimination in philosophy. Philosophical Psychology, 33(4), 511-548.

Members of the field of philosophy have, just as other people, political convictions or, as psychologists call them, ideologies. How are different ideologies distributed and perceived in the field? Using the familiar distinction between the political left and right, we surveyed an international sample of 794 subjects in philosophy. We found that survey participants clearly leaned left (75%), while right-leaning individuals (14%) and moderates (11%) were underrepresented. Moreover, and strikingly, across the political spectrum from very left-leaning individuals and moderates to very right-leaning individuals, participants reported experiencing ideological hostility in the field, occasionally even from those on their own side of the political spectrum. Finally, while about half of the subjects believed that discrimination against left- or right-leaning individuals in the field is not justified, a significant minority displayed an explicit willingness to discriminate against colleagues with the opposite ideology. Our findings are both surprising and important because a commitment to tolerance and equality is widespread in philosophy, and there is reason to think that ideological similarity, hostility, and discrimination undermine reliable belief formation in many areas of the discipline.

Their results:

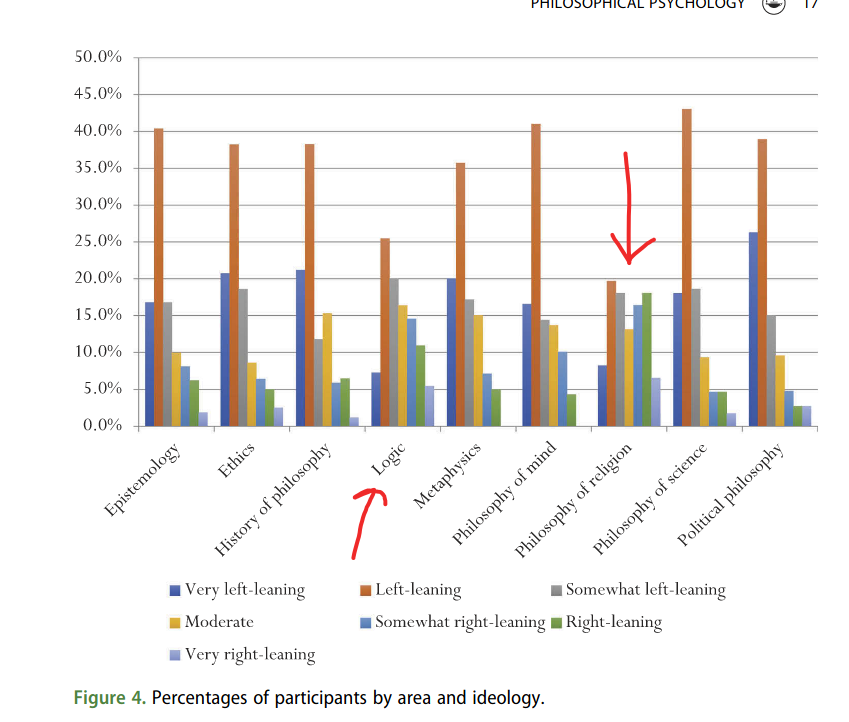

So people who studied philosophy of religion and philosophy of logic are less socialist, but still overall quite far left of center. The former is easy to explain as being a minority hold-out area of the smarter people who should have studied theology, but chose to take up the battle in philosophy (Plantinga types). They also asked about analytic vs. continental philosophy for a more broad grouping:

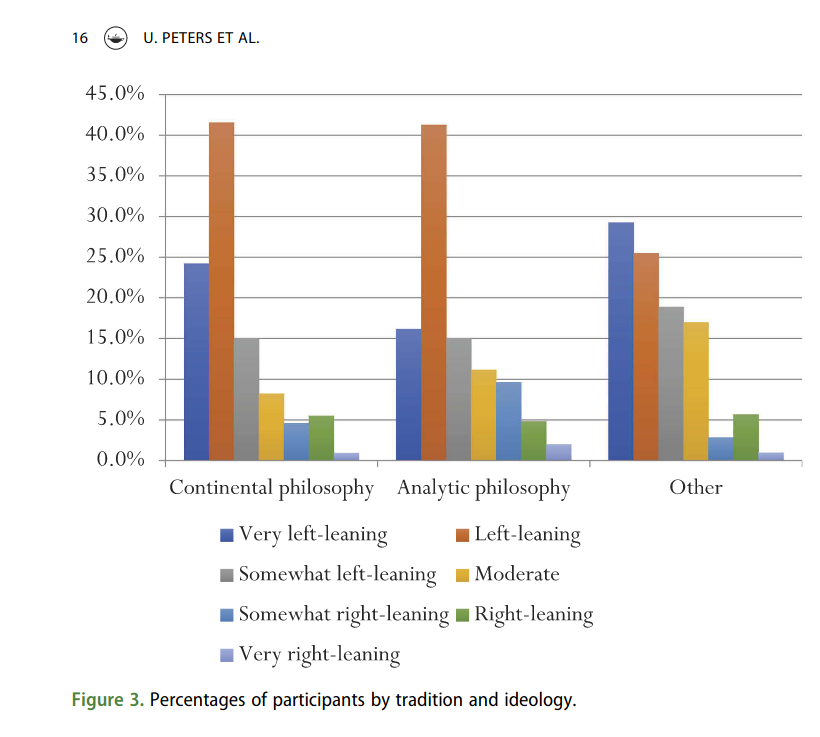

Analytic philosophers were somewhat less socialist, but not impressively so. “Other” philosophy, I guess that means mostly non-Western, was even more left-wing than regular continental.

Since the data were public, I looked at whether this logic finding was robust to controls and beyond chance level:

(Standard errors in parens.)

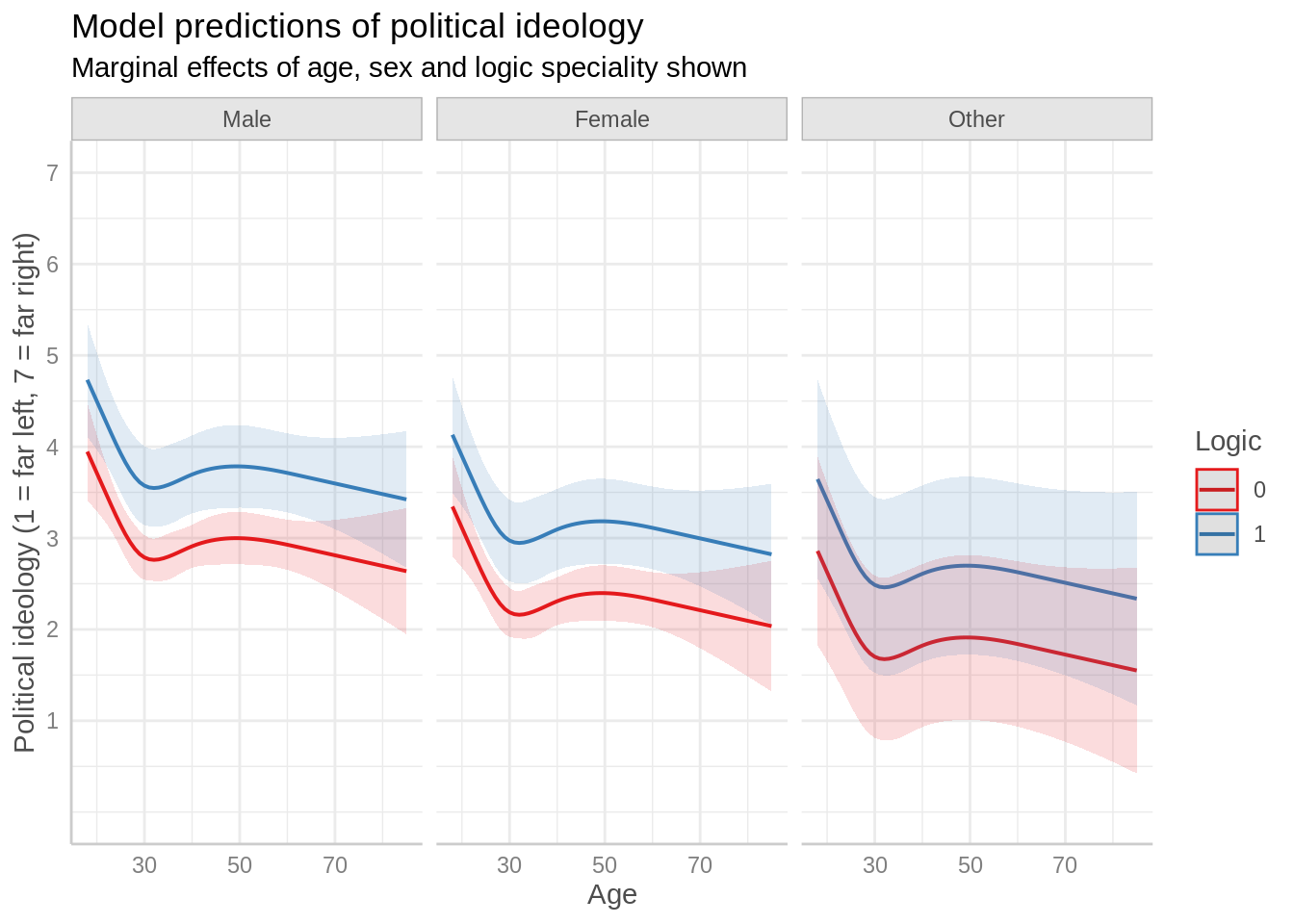

They asked each person about their specialty, and people could select more than one option. As such, I coded everything as a binary dummy (yes/no). Logic and religion specialty both show strong associations with being more conservative/less socialist (p < .001). This is true also when controlling for race/ethnicity, age and sex. Note the effect size for female, which fits with the feminization of academia. More women means more left-wing overall. The phenomenology field is more left-wing too, I guess because of its schizoid style. Schizophrenics are notably left-wing. There is also a smaller left-wing association for political philosophy. There weren’t any notable associations for race/ethnicity, but probably just because of small samples, considering the standard errors shown.

The model predictions by age, sex, and logic specialty looks like this:

Overall, the verdict is: true, logic focused thinkers seem to be less left-wing. I guess it fits well within the (hot) emotion vs. (cold) reason difference, which tends to map unto left vs. right-wing politics. Few people can get emotionally excited about markets, but markets work.