James Lee, authors of many GWAS studies wrote a piece in 2022 entitled Don’t even go there saying that NIH is increasingly censorious regarding data access. Since it is short, I will quote it in its entirety:

A policy of deliberate ignorance has corrupted top scientific institutions in the West. It’s been an open secret for years that prestigious journals will often reject submissions that offend prevailing political orthodoxies—especially if they involve controversial aspects of human biology and behavior—no matter how scientifically sound the work might be. The leading journal Nature Human Behaviour recently made this practice official in an editorial effectively announcing that it will not publish studies that show the wrong kind of differences between human groups.

American geneticists now face an even more drastic form of censorship: exclusion from access to the data necessary to conduct analyses, let alone publish results. Case in point: the National Institutes of Health now withholds access to an important database if it thinks a scientist’s research may wander into forbidden territory. The source at issue, the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP), is an exceptional tool, combining genome scans of several million individuals with extensive data about health, education, occupation, and income. It is indispensable for research on how genes and environments combine to affect human traits. No other widely accessible American database comes close in terms of scientific utility.

My colleagues at other universities and I have run into problems involving applications to study the relationships among intelligence, education, and health outcomes. Sometimes, NIH denies access to some of the attributes that I have just mentioned, on the grounds that studying their genetic basis is “stigmatizing.” Sometimes, it demands updates about ongoing research, with the implied threat that it could withdraw usage if it doesn’t receive satisfactory answers. In some cases, NIH has retroactively withdrawn access for research it had previously approved.

Note that none of the studies I am referring to include inquiries into race or sex differences. Apparently, NIH is clamping down on a broad range of attempts to explore the relationship between genetics and intelligence.

What is NIH’s justification? Studies of intelligence do not pose any greater threat to the dignity of their participants than research based on non-genetic factors. With the customary safeguards in place, research activities such as genetically predicting an individual’s academic performance need be no more “stigmatizing” than predicting academic performance based on an individual’s family structure during childhood.

The cost of this censorship is profound. On a practical level, many of the original data-generating studies were set up with the explicit goal of understanding risk factors for various diseases. Since intelligence and education are also risk factors for many of these diseases, denying researchers usage of these data stymies progress on the problems the studies were funded to address. Scientific research should not have to justify itself on those grounds, anyway. Perhaps the most elemental principle of science is that the search for truth is worthwhile, regardless of its practical benefits.

NIH’s responsibility is to protect the safety and privacy of research participants, not to enforce a party line. Indeed, no apparent legal basis exists for these restrictions. NIH enforces hundreds of regulations, but you will search in vain for any grounds on which to ban “stigmatizing” research—whatever that even means.

The restrictions appear to be invented to impede research on certain topics that anonymous bureaucrats with ideological motivations have decided are out of bounds. It’s impossible to know whether senior NIH officials have instigated the restrictions or merely accepted them tacitly. Perhaps they are unaware of the problem; officials far down the bureaucratic ladder are responsible for approving specific applications.

NIH has historically enjoyed high levels of public confidence in its professionalism and integrity. That trust is now deteriorating. The decline began with evidence that its personnel may have been complicit in blocking investigations of the possibility that Covid-19 escaped from a Chinese laboratory. The restrictions on scholars’ access to the dbGaP don’t have nearly the same public visibility as the Covid story, but they strike equally at the heart of NIH’s integrity.

The federal government was under no obligation to assemble the magnificent database that is the dbGaP. Now that it has done so at taxpayer expense, however, it does have an obligation to provide access to that database evenhandedly—not to allow it for some and deny it to others, based on the content of their research.

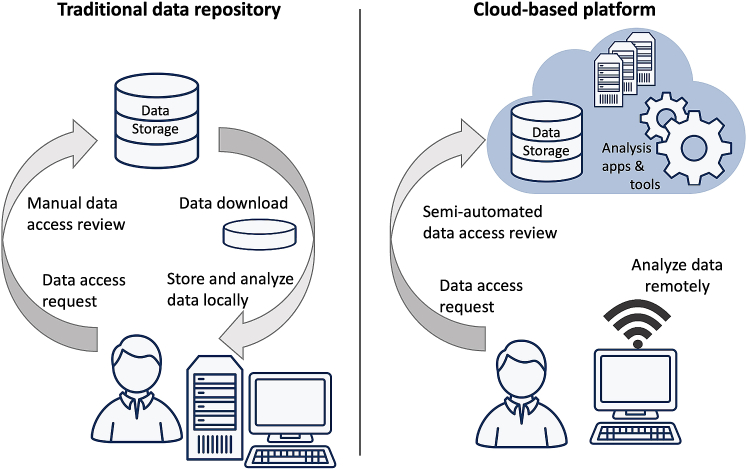

Aside from getting approved to the dbgap network (this can take months because of the bureaucracy), researchers also have to apply for access to specific datasets once they are approved as researchers. Each dataset has its own rules for application. This typically requires coming up with a research plan and showing an ethics board approval. Furthermore, the datasets are increasingly being siloed up in online research environments, called variously Research Analysis Platform (UKBB), Researcher Workbench (All of us), collectively called cloud-based platforms. It contrasts like this with the traditional approach:

There are some advantages and disadvantages with this centralized cloud approach:

- All research work is monitored so abuse can be easily identified and access revoked (e.g., don’t use the data to identify participants for illegal purposes). However, it is also very easy to censor research topics researchers and bureaucrats dislike.

- Foreign agents cannot steal the data because the data cannot be downloaded (e.g. Chinese spies).

- The costs of maintaining storage and computing power is borne by the NIH, researchers don’t need to invest in expensive local equipment.

As James Lee writes, there is a lot of censorship currently. Take for instance the recent brouhaha when researchers plotted the ancestry data in All of us to the dismay of some other researchers. However, that could be about to change. Since there is little risk of data misuse when researchers can’t store it locally, the data access requirements should be lowered in return. So although this approach has been in part set-up so that greater censorship could be enforced, the centralized nature of it also allows for a single clean sweep to remove all the censorship and make everything nicer and more efficient.

Here’s a simple 3-part proposal:

- Remove the need to apply for specific datasets and remove IRB requirements. If one is approved for dbgap access, then one is approved for all datasets. This means a lot of bureaucracy can be removed, and scientists can’t act as gatekeepers to data they collected using federal funding. Science will be faster, better, and cheaper to do.

- Charge researchers for their use of the platforms to offset the costs.

- Make access to dbgap streamlined and automatic. Anyone should be able to gain access, whether these are university professors, private sector researchers, students, or hobbyists. A scientist is a scientist is a scientist.