Most people know that married couples tend to be more similar than expected by chance for many attributes whether age, race, politics, intelligence, personality, music taste and so on. This is usually referred to as assortative mating, since there is an assortment for the trait in question. It is possible to have the opposite — disassortative mating — but this is pretty rare. I mean, rare aside from the obvious case of sex, which shows near perfect opposite matching for married couples (i.e., they are heterosexuals).

There is discussion about disassortative mating for certain immune system markers. There is a region of the human genome called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). In humans, this region is on chromosome 6 and is called the human leukocyte antigen. The point of this region is to be really different across humans because it affects certain default parameters of the immune system. Larger animals need to defend themselves against the fast-evolving microorganisms and they do this by shuffling the genes real hard in this region. The point of this is that when a novel pathogen comes along, the animals are already very different in terms of these default parameters, so that hopefully some of them will by coincidence be resistant to the new pathogen without having to evolve resistance first. Anyway, so the point of this region then is to be as different as possible, and thus mating with someone who is dissimilar for these genes would be a good idea in order to maximize the survival chances of offspring. Humans are supposedly weakly able to tell MHC variation by smell, and smell is important for the formation of romantic relationships.

Seems far fetched? There is a large study from 2019 looking at this:

- Dandine-Roulland, C., Laurent, R., Dall’Ara, I., Toupance, B., & Chaix, R. (2019). Genomic evidence for MHC disassortative mating in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 286(1899), 20182664.

Although pervasive in many animal species, the evidence for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) disassortative mating in humans remains inconsistent across studies. Here, to revisit this issue, we analyse dense genotype data for 883 European and Middle Eastern couples. To distinguish MHC-specific effects from socio-cultural confounders, the pattern of relatedness between spouses in the MHC region is compared to the rest of the genome. Couples from Israel exhibit no significant pattern of relatedness across the MHC region, whereas across the genome, they are more similar than random pairs of individuals, which may reflect social homogamy and/or cousin marriages. On the other hand, couples from The Netherlands and more generally from Northern Europe are significantly more MHC-dissimilar than random pairs of individuals, and this pattern of dissimilarity is extreme when compared with the rest of the genome. Our findings support the hypothesis that the MHC influences mate choice in humans in a context-dependent way: MHC-driven preferences may exist in all populations but, in some populations, social constraints over mate choice may reduce the ability of individuals to rely on such biological cues when choosing their mates.

The idea here is to compare the genetic similarity of couples in whole genome in comparison to just the MHC region. As can se seen, every dataset except for the UK shows a positive level of overall genome similarity. I would guess the UK is a sampling error here, as results from the UK Biobank shows genetic assortative mating in the UK. If the authors had included confidence intervals here for their R value, it would have been helpful with interpretation. Looking at the MHC region, every sample except for Israel shows disassortative mating per theory. Why not Israel? I can’t tell if this is sampling error, or perhaps Jews are not selected so much against inbreeding as the other Europeans. This is possible as Jews are the most inbred group of the ones studied here.

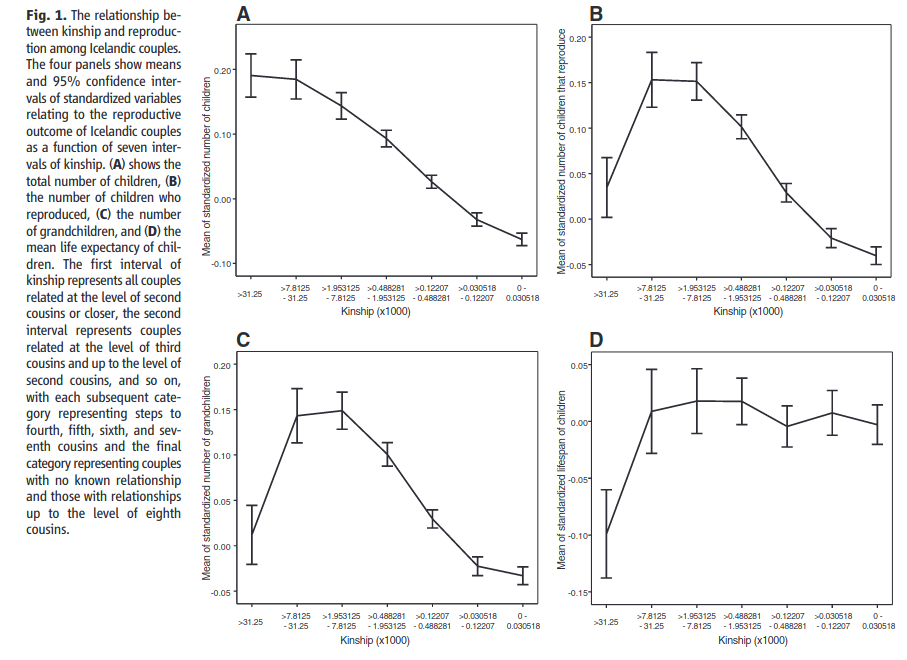

As mentioned above, genetic relatedness is in general related to more compatibility. In fact, the famous Icelandic kissing cousins study found these results:

Previous studies have reported that related human couples tend to produce more children than unrelated couples but have been unable to determine whether this difference is biological or stems from socioeconomic variables. Our results, drawn from all known couples of the Icelandic population born between 1800 and 1965, show a significant positive association between kinship and fertility, with the greatest reproductive success observed for couples related at the level of third and fourth cousins. Owing to the relative socioeconomic homogeneity of Icelanders, and the observation of highly significant differences in the fertility of couples separated by very fine intervals of kinship, we conclude that this association is likely to have a biological basis.

Mind you that 3-4th cousins are quite unrelated, but still, the principle applies.

But we can take this further. If humans like mating with people who are genetically similar, why not go for a better deal? A sibling or parent? While this has been done sometimes in history, it was generally not a preferred mate choice. Of course, we normally just call this incest and that is sufficient to evoke moral overtones. Studies do show that matings that are too close genetically tend to result in worse phenotypes due to recessives being expressed (seen in the plot above B-D). So humans, and some other animals, must have some kind of mechanism for avoiding incest. This has been studied quite a bit in animals, and also in humans to a lesser extent. In humans it is generally known as the Westermarck effect, after Swedish Finn Edvard Westermarck, who hypothesized that spending childhood together hampers later sexual interest (though not completely). This idea was later studied in Israeli Kibbutzim because the communists had decided that parents rearing their own children was reproducing social inequalities (which is true), and so the children should be collectively reared instead. Wikipedia provides the following summary of the evidence:

In the case of the Israeli kibbutzim (collective farms), children were reared somewhat communally in peer groups, based on age, not biological relations. A study of the marriage patterns of these children later in life revealed that out of the nearly 3,000 marriages that occurred across the kibbutz system, only 14 were between children from the same peer group. Of those 14, none had been reared together during the first six years of life. This result suggests that the Westermarck effect operates during the period from birth to the age of six.[2]

In Shim-pua marriages, a girl would be adopted into a family as the future wife of a son, often an infant at that time. These marriages often failed, as would be expected according to the Westermarck hypothesis.[3]

Studies show that cousin-marriage in Lebanon has a lower success rate if the cousins were raised in sibling-like conditions, first-cousin unions being more successful in Pakistan if there was a substantial age difference, as well as reduced marital appeal for cousins who grew up sleeping in the same room in Morocco. Evidence also indicates that siblings separated for extended periods of time since childhood were more likely to report having engaged in sexual activity with one another.[4]

Looking over academic work, I find that many researchers consider the evidence kinda plausible but not really convincing. Two studies find the effect is stronger in women, which is theory expected (because they bear higher costs of bad matings), and women mainly control dating choices, so there is less reason to maintain this mechanism in men. I think, though, on balance of evidence, humans avoid incest in some way across most cultures, so something like the Westermarck effect will be true, even if that version is maybe not entirely right.

Assuming for the sake of argument that Westermarck effect is true, and people avoid romanticizing their family members due to childhood experiences, what about strongly related people who didn’t spend childhoods together? There are such people: adoptees and half-siblings reared different locations. An interesting example of the latter would be children conceived by the same sperm donor father, or egg donor mother, who usually have no contact with the donor or each other until adulthood. Do these people experience sexual interests that are confusing and feel wrong? Perhaps there is a study of this, but I haven’t seen it. I have however seen some anecdotes:

Q. Nasty Surprise: When my wife and I met in college, the attraction was immediate, and we quickly became inseparable. We had a number of things in common, we came from the same large metropolitan area, and we both wanted to return there after school, so everything was very natural between us. We married soon after graduation, moved back closer to our families, and had three children by the time we were 30. We were both born to lesbians, she to a couple, and me to a single woman. She had sought out her biological father as soon as she turned 18, as the sperm bank her parents used allowed contact once the children were 18 if both parties consented. I never was interested in learning about that for myself, but she felt we were cheating our future children by not learning everything we could about my past, too. Well, our anniversary is coming up and I decided to go ahead and, as a present to my wife, see if my biological father was interested in contact as well. He was, and even though our parents had used different sperm banks, it appears so did our father, as he is the same person. On the one hand, I love my wife more than I can say, and logically, done is done, we already have children. I have had a vasectomy, so we won’t be having any more, so perhaps there is no harm in continuing as we are. But, I can’t help but think “This is my sister” every time I look at her now. I haven’t said anything to her yet, and I don’t know if I should or not. Where do I go from here? I am tempted to burn everything I got from the sperm bank and just try to forget it all, but I’m not sure if I can. Please help me figure out where to go from here.

There is even an official policy to limit children per sperm donor in order to reduce this potential problem (‘accidental incest‘):

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine have created guidelines that have been established for a very long time that advise a limit of no more than six (6) egg donation cycles for each woman who is an egg donor. Along with the fact that egg donors are typically smart, bright, intelligent and thoughtful – they are counseled by a psychologist and/or therapist on both the medical and psychological aspects ( in other words the good, the bad, and the ugly) of egg donation. During an egg donors meeting with a mental health professional the discussion of repeat donation is talked about, how it could affect their health, how many times they should donate and the risk factors involved.

Returning to adoptees, there is one famous contemporary case: Patrick Stübing and Susan Karolewski:

Stübing (a locksmith) is the third of eight children born into a low income family. He was fostered at age 3 due to being attacked with a knife by his alcoholic father. He was adopted by his foster parents at age 7, with whom he lived in Potsdam. His sister was born in 1984, on the day their parents’ divorce was finalized. Stübing did not meet his mother and biological family until 2000 when he was 23.[2] According to Stübing, the relationship between him and his sister became incestuous in 2001, six months after their mother died of a heart attack.[2]

Karolewski is mentally disabled, semi-literate, and was 16 at the time of giving birth to their first child in October 2001.[2] The relationship was discovered when their first child was born. A nurse suspected Stübing was the father of his sister’s child and contacted police. Upon his second conviction of incest, Stübing was sentenced to ten months in prison. He was later sentenced to two and a half years in prison for his third incest conviction. During the latter sentence, Karolewski had a relationship with an unknown man who claimed to be her boyfriend and had a child with him, which she gave up rights to after Stübing was released from prison.

As can be seen from this description, this is not really a good case to discuss. One might even speculate that the reason this pair went for it, and got caught is that they are pretty dumb. Most people who experience this kind of attraction — genetic sexual attraction — are going to be aware of the stigma against it, and the genetic consequences of ignoring it. Thus, they are not going to act on it, or if they do, keep it secret, and not actually have children together. Wikipedia also covers this topic, but with a maybe surprising angle:

Genetic sexual attraction is a concept in which a strong sexual attraction may develop between close blood relatives who first meet as adults. There is no evidence for genetic sexual attraction being an actual phenomenon,[1] and the hypothesis is regarded as pseudoscience.[2]

Woah, pseudoscience! “No evidence!”. So we check their sources, and we find that it is basically nothing serious. The main source is an article in Salon magazine from Woke Woman journalist. Laughably stupid. Anyway, Wikipedia does helpfully mention that these cases are actually reported by researchers who study adoptees. Let’s look at some example:

- Greenberg, M., & Littlewood, R. (1995). Post‐adoption incest and phenotypic matching: Experience, personal meanings and biosocial implications. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 68(1), 29-44.

Following Britain’s Access to Birth Records Act of 1975, which enabled anyone over 18 who had been adopted to trace their parents, an increasing number of reunions have occurred under precisely these circumstances. In anticipation that personal difficulties might follow tracing, a counselling clause was included under Section 26 (now 51) of the Act. A number of counselling agencies then developed, initially intending to focus on the problems faced by the adoptive parents, but increasingly responding to the adoptees, the biological parents and other relatives (Sawbridge, 1988). As the number of successful traces has increased, the focus of counselling includes problems that arise following reunions. Among these complications is a phenomenon sometimes referred to by counsellors as ‘genetic sexual attraction’ (GSA): powerful erotic feelings developing between reunited relatives (Strickland, 1993). Estimates of the frequency of GSA vary2; its recognition and resolution have proved difficult in conventional counselling because both clients and therapists recognize that acting on these feelings is illegal. Counsellors are torn between maintaining the conventional psychotherapeutic distance, and a wish to actively prevent sexual attachments which they recognize as unusually powerful.

In order to clarify some of the issues, one of us (M.G.) set up a project at a London post-adoption agency both to discuss GSA with the counsellors and to interview clients who had personal experience of it (Strickland, 1993). These people were self- selected in that they had requested counselling and were also willing to be interviewed for research purposes, or who had responded to a notice placed in a post-adoption newsletter briefly describing the issues and inviting responses. In addition, many individuals phoned or wrote (sometimes anonymously) describing experiences of GSA; unlike those formally interviewed, many of these were the adoptive parents.

The instances summarized here3 are derived from a semi-structured interview with informants. The data collected included: social and demographic background and personal relationships including marriage; a birth history with details of the biological parent and siblings; similar data about the adoptive family, the circumstances of the adoption and how much information had been provided and when; a developmental history which included any earlier medical or psychological problems, together with informants’ description of their personality; details of the reunion, how it was organized, by whom, and feelings at the time. Informants were asked about any erotic interests -when they emerged, their quality and consequences. Details of any sexual relationship were recorded: informants were asked to comment on the outcome, how they made sense of it, whether any particular complications had arisen, and whether they had wished, or found it possible, to continue the relationship in a non-sexual way.

Findings on interview: Experience and personal meanings

Nine questionnaires were completed fully, eight of them by informants who had been adopted as children and then united as adults with their biological family. It proved difficult to obtain interviews with a biological parent (the ninth case only), and the findings are thus essentially the experiences of those adopted. Five questionnaires were completed face to face, and four by people declining an interview but agreeing to complete the detailed questionnaire. All nine -seven women, two men – reported erotic sentiments. Three had proceeded to sexual intercourse – one case of daughter/father and two cases of sister/sister. The other five reported intense erotic, but not genital, intimacy (three sister/brother, two son/mother, one mother/son). The social background of informants varied from higher professional to unskilled. All nine were white. Three had degrees; all were articulate. Adopted before six months of age, all except one were brought up knowing they had been adopted; the exception was a family in which ‘everybody knew but nobody talked about it’. The adoptive milieu seems to have varied from happy to one where the young girl was repeatedly told she had ‘bad blood coming out’. There were two instances of suggestions having been made by the adoptive families about previous incestuous relationships in the child’s biological family. Individual mental health before the reunion varied: there were two resolved instances of eating disorders (one with a continuing alcohol problem), one of intermittent agoraphobia, and one informant recalled what might have been a behavioural disorder in early childhood. None had had sexual relationships inside their adoptive family, or as a child with other adults. The average age on contacting the biological family was 37. All had previously had heterosexual relationships, one also a lesbian relationship, five were in a marriage or stable partnership at the time of tracing. Informants often represented themselves as lacking in confidence yet as what might be glossed as ‘vital and nervy’: they had anticipated that their biological families would be livelier than their adoptive families who were often considered staid or even cold.Case 2. (Married professional woman with three children who traces her biological family when she is 40, and meets her sister.) Jane knew I was my mother’s daughter just by looking at me. I took my shoes off to show my feet, my hands and knuckles, photographs of me from the back. It began with fascination with similarities and differences. We needed to be together and still do. Last year Jane and her husband were apart whilst selling a house and we spent increasing times together. I liked feeling her against me, her hands, leaning. It was part of belonging — what I wanted from my mum because I never belonged anywhere. (She visits the post-adoption centre and discusses the situation; they warn her of the possible consequences which she denies: ‘All we want is a cuddle!’) It just felt like falling in love. It was someone I’d belong to, it’s my sister, it’s nice, I’m lucky. We couldn’t get enough time together. A goodbye kiss on the cheek, then the lips. No resistance. It seemed right, though it seems awful now. (The two families go on holiday together.) That’s where it went below the waist, I never thought it would happen. I just wanted to be close. (The genital relationship has continued sporadically. She says that if it were not for her own children the two sisters would live together, but does not see herself nor Jane as lesbian. She feels both the attraction and sex are mutual.)

Footnote 2: Some post-adoption counsellors reported to us that it was fairly uncommon, others that it was virtually universal when clients were asked sensitively. We would estimate from their reports that over 50 per cent of current clients seen in London have experienced strong sexual feelings in reunions. The term ‘genetic sexual attraction’ was coined by Barbara Gonyo (1987) who has described it in various post-adoption newsletters, and is preferred by counsellors to the emotive term ‘incest’.

You can read the rest of the cases yourself, but this kind of thing is obviously not so outlandish, but rather based on well established findings from assortative mating and marital similarity. The fact that no one has currently done a large-scale survey in a national adoption/twin register to properly estimate prevalence does not mean it is false or even pseudoscience.

- Segal, N. L. (2013). Twin studies of multiple myeloma: a research foundation and recent findings. Twin Research and Human Genetics: the Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 16(2), 645-6.

Opposite-Sex Twins and Sexual Attraction

Twins reveal a great deal about human behavior just by being themselves. The question of sexual attraction between opposite-sex twins reared apart has been addressed in prior issues of Twin Research and Human Genetics (Segal, 2008, 2011). A new case recently came to my attention when I attended the III Congreso des Mentes Brillantes in Madrid, Spain, in November 2012. The male member of an opposite- sex twin pair informed his spouse that he been adopted and reared apart from his twin sister. His wife conducted an extensive search to find the sister and was successful after one and a half years. However, she eventually learned that her husband was having a sexual relationship with his newly found twin. Behind the shock value of this discovery is information about who we are attracted to, and why. According to the informant, the twins recognized similarities between themselves and were possibly making up for lost time. ‘Perhaps his sister was a female version of himself ’. There have been other such cases, mostly between re-united male–female twins who were unaware of their biological relatedness. However, as I discuss in my recent book on the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart (Segal, 2012), we observed flirtatious behaviors between several reunited male–female co-twins who knew that they were twins. The concept of genetic sexual attraction, well known among the adoption community but less appreciated outside it, refers to the strong sexual feelings that may be experienced between reunited relatives (e.g., mothers who relinquished their sons for adoption; Gonyo, 1987).

The cited works are:

- Segal, N. L. (2008). Opposite-sex twins: When they marry. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 11, 236–239.

- Segal, N. L. (2011). Reunited twins: Spouse relations. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 14, 290–294.

- Segal, N. L. (2012). Born together-reared apart: The landmark Minnesota twin study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

This paper reports some additional anecdotes:

- Gladstone, J., & Westhues, A. (1998). Adoption reunions: A new side to intergenerational family relationships. Family Relations, 177-184.

Other adoptees, especially those in “distant” relationships, referred to obligation as the primary motivator for their maintaining contact with a birth relative. Feelings of guilt and confusion also appeared to drive relationships. One adoptee, who had a “tense” relationship with her birth sister, remarked that “I do it through guilt now, I guess. I just wonder what I got myself into because I’m not getting anything from it.” Another adoptee had a “distant” relationship with her birth brother after realizing that they were sexually attracted to each other. However, unlike those situations in which a birth relative made an actual sexual advance, this adoptee recognized that she too was sexually attracted to her birth brother and then distanced herself from him partly because of the guilt that she felt. Other adoptees, who had “ambivalent” relationships with their birth relatives, tried to affirm their loyalty towards their adoptive parents, possibly so that they wouldn’t feel guilty maintaining a relationship with a birth parent. As one adoptee commented, “I met a birth father, and I had to make sure that my dad was all right with the fact that this man would never replace him as my dad.”

I found a lot more sources that discuss these anecdotes, so we know they are quite common. To find them, look for citing papers of the ones above, e.g. here and here.

Other sources cited which I couldn’t find a copy of:

- Gonyo, B. (1987). Genetic sexual attraction. American Adoption Congress Decree, 4, 1–5.

- Childs, R. M. (1998). Genetic sexual attraction: Healing and danger in the reunions of adoptees and their birth families. Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology.

- Traver, E. K. (2000). Dethroning Invisibility: Talk stories of adult Korean adoptees. University of Denver.