Probably many of you have seen this meme about aposematic hair color:

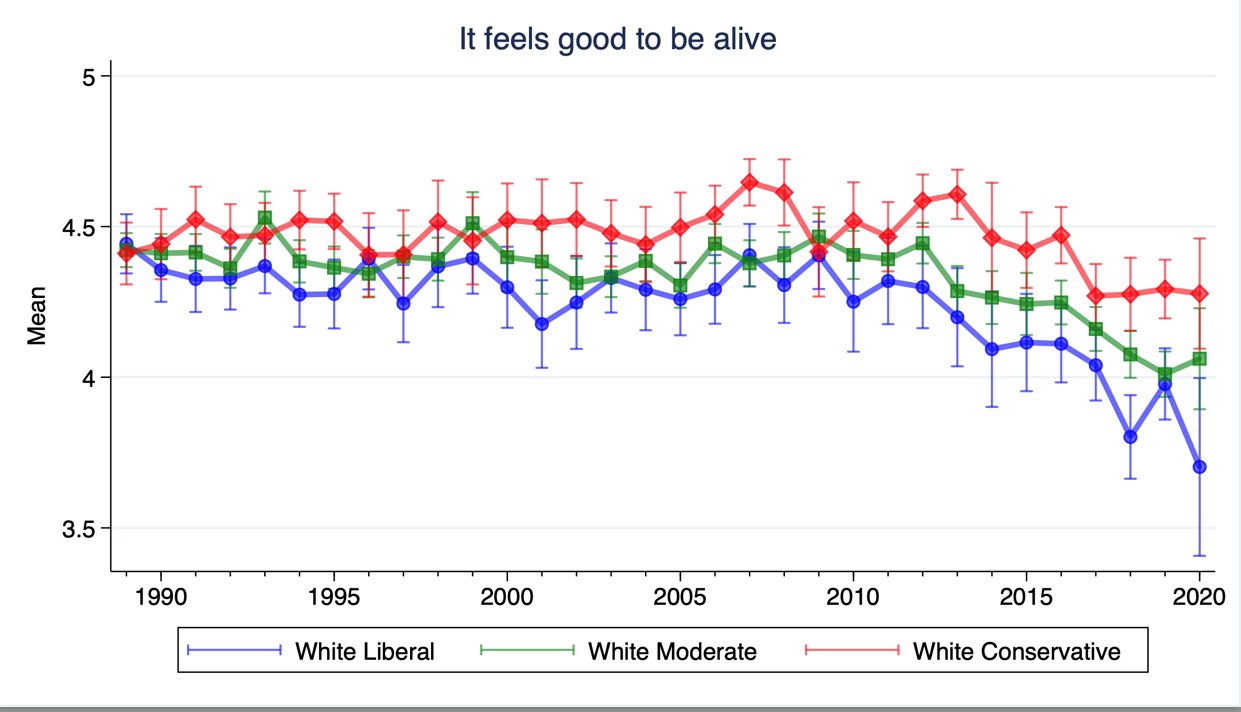

For those not into memes: the idea is that poisonous animals advertise their dangerousness by bright colors to scare away predators. Humans appear to do the same, as those who are poisonous — mentally ill — color their hair in bright dangerous looking colors. Since this meme was made in about 2014, we’ve seen a strong increase in the number of people with unnatural hair colors, in the same time we have seen a rise in mental illness in left-wingers. Coincidence? Probably not right. Zach Goldberg provided me with this example plot, but there’s a lot more evidence.

However, is it really true though? Is unnatural hair color associated with mental illness, or are we being mislead by a few prominent people with this hair style who appear very mentally ill? We decided to find out using the venerable OKCupid dataset. Here’s the study:

- E. Dutton, Kirkegaard, E. O. W. (2022). Blue Hair and the Blues: Dying Your Hair Unnatural Colours is Associated with Depression. Psychreg Journal of Psychology.

A number of lines of evidence, such as studies of religious converts and members of conspicuous subcultures, have found a relationship between holding and expressing a strong counter-cultural identity and mental instability. Here we test whether dying your hair an unnatural colour – something which conspicuously expresses non-conformity – is related to mental instability, using a large dataset of online daters (OKCupid dataset, about n=14k used in this study). We find the expected pattern, which was moderate in size (p = -033 to -0.23, depending on controls). This pattern persisted even when controls for age, race, sex, sexual orientation, body type, intelligence, polyamory, vegetarianism, and political beliefs were included.

(Yeah, I don’t know where Dutton found this journal either. It doesn’t even have a DOI, but whatever.)

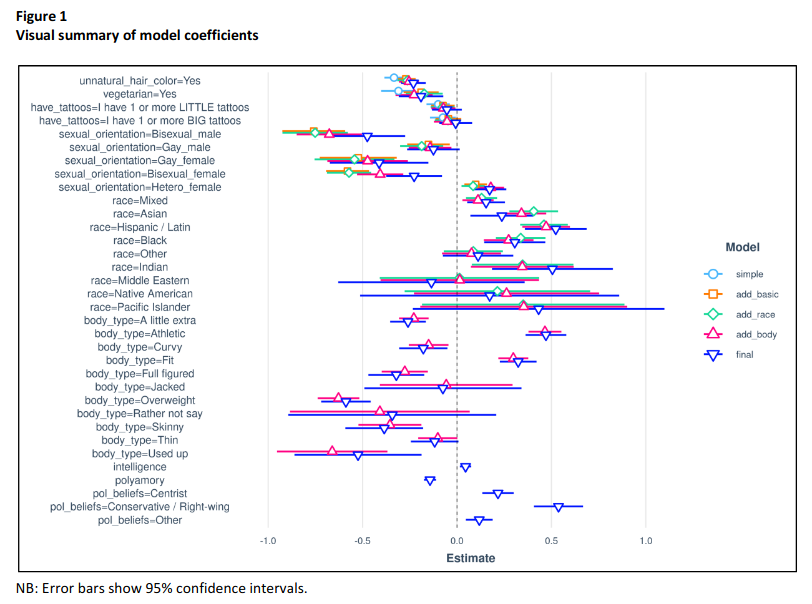

The model figure summarizes the model results:

In words:

Results show many points of interest. First, in the simplest models that include only our key variables of self-presentation, we see that unnatural hair colour predicts mental illness with a moderately large effect size, β = -0.33, and there is also a notable effect size for vegetarianism, β = -0.31. This relationship may exist due to vegetarianism being an expression of a need for a strong identity or perhaps because a high level of anxiety extends to anxiety about harm to animals. Having tattoos is comparatively a much weaker signal, with effect sizes estimated around -0.10. Across the models, we add progressively more potential confounder, such as age, sex and sexual orientation, political ideology and so on. However, we see that despite the inclusion of so any controls, unnatural hair colour remains a fairly potent predictor of mental illness, with an effect size in the final model of β = -0.23. Vegetarianism also retains most of its validity, ending in the final model with β = -0.19. For the covariates, we see familiar findings, with negative effects for non-heterosexuals compared with the reference group of heterosexual females. Somewhat strangely, we find that heterosexual men are higher in mental illness in this sample, perhaps reflecting self-selection of men who resort to dating sites as opposed to finding dates in physical settings such as bars. For race, we see that most non-whites have better mental health, at least insofar as self-report is concerned (see Rushton, 1995). This is in line with much evidence on European-descended people’s relatively poor mental health in Western countries.

For body type, we see that deviation from the baseline category of “average” is associated with expected effects: better mental health for people who are relatively fit (e.g., athletic, β = 0.47), and worse for those who are unhealthy (e.g., full-figured, β = -032). Intelligence shows a weak positive effect (β = 0.05), in line with research on the general factor of psychopathology (Caspi et al., 2014), though weaker than expected. The non-traditional dating pattern of polyamory shows a moderate negative effect of -0.14, contrary to a very small study (Bali, 2020). Finally, political ideology shows negative effects of non-conservative view, especially left-wing liberal (β = -0.54, opposite that of the conservative reference), also in line with recent work (Bernardi, 2020: Kirkegaard, 2020). Essentially all the covariates had some detectable effect given our large sample size (most p values were p < .001).

A strength and a weakness of the study is that, obviously, OKCupid being a dating site, our measure of mental illness is not great. Nevertheless, it works. We scored a general factor of mental illness based on the top 5 questions here:

Despite our measures being relatively modest, the results work out well. There’s no need to p-hacking anything when you study things that are true and strong. If you still think weak measures is a big issue, consider the fact that unreliable measures will in general decrease observed associations, not make them larger. So the fact that we can see correlations/betas of .19 to .33 means that the true association is quite likely much stronger, maybe .50. Additionally, we see relations to known to other constructs we already know mental illness is correlated with, e.g. political leftism (d = .50!) and vegetarianism.

For those wondering what else one could do with this fantastic dataset, the list of questions is here. And the data you can download here. Read the original paper first. Post any good ideas you come up with in the comments.