A friend of mine sent me this article for evaluation. Basically he thought the findings were too wild to be believed:

- Brame, R., Bushway, S. D., Paternoster, R., & Turner, M. G. (2014). Demographic patterns of cumulative arrest prevalence by ages 18 and 23. Crime & Delinquency, 60(3), 471-486.

In this study, we examine race, sex, and self-reported arrest histories (excluding arrests for minor traffic violations) from the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY; N = 7,335) for the period 1997 through 2008 covering cumulative arrest histories through ages 18 and 23. The analysis produces three key findings: (1) males have higher cumulative prevalence of arrest than females; and (2) there are important race differences in the probability of arrest for males but not for females. Assuming the missing cases are missing at random, about 30% of black males have experienced at least one arrest by age 18 (vs. about 22% for white males); by age 23 about 49% of black males have been arrested (vs. about 38% for white males). Earlier research using the NLSY showed that the risk of arrest by age 23 was 30%, with nonresponse bounds [25.3%, 41.4%]. This study indicates that the risk of arrest is not evenly distributed across the population. Future research should focus on the identification and management of collateral risks that often accompany arrest experiences.

So, already by age 23, 49% of Black men and 38% of White men had been arrested. Woah! Sounds very high? Well, they also note that their data is based solely on survey data, that is, self-report. Maybe criminals lie on surveys, claiming they haven’t been arrested even when they have? What about people who didn’t fill out the surveys, they are probably higher in arrest probabilities. Still, the authors try to adjust for these issues, and still find numbers in this area. In any case, adjusting for these factors would make the numbers higher not lower.

Maybe the data are just old? Crime rates are falling, so presumably lifetime arrests are too. Is there anything newer? Yep, Add Health is the follow-up survey to NLSY 97, and the usual same suspects did a paper for it too:

- Barnes, J. C., Jorgensen, C., Beaver, K. M., Boutwell, B. B., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Arrest prevalence in a national sample of adults: The role of sex and race/ethnicity. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(3), 457-465.

We analyzed the prevalence of arrest (ages ranged from 24 to 34) across sex and race/ethnicity by drawing on nationally representative data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Findings revealed 30 % of U.S. adults (aged 24–34) reported being arrested at least once in their lifetime. Prevalence of lifetime arrest for males (43 %) was more than two times that of females (17 %). Arrest risk was not homogenous across racial/ethnic groups with 19 % of Asian/Pacific Islander respondents reporting an arrest, 29 % of White respondents reporting an arrest, 38 % Black respondents reporting an arrest, and 40 % of American Indian/Native Americans reporting an arrest. The current results support recent evidence gleaned from alternative sources but suggest arrest risk is not homogenous across sex or racial/ethnic categories.

This data has the same issue of self-report though. What about official records then? The authors themselves discuss this:

The two studies discussed above by Brame and colleagues analyzed self-report data. Piquero, Schubert, and Brame (2014) used both self-reported arrests and official arrest records to examine correspondence between these two measures longitudinally within a sample of serious youthful offenders from the Pathways to Desistance study. The study found a moderate level of congruence between self-report measures and official records and that the agreement was stable over time. Additionally, there were few sex or racial differences in correspondence between measures. The study found that males consistently had a higher arrest prevalence than females with males being nearly twice as likely to have been arrested at each wave. Additionally, blacks were consistently more likely to have been arrested at each wave than other racial/ethnic groups. The findings from Piquero et al. suggest that self-report arrest data are a fairly good representation of official reports of arrest.

Sounds good, but not when we take a closer look:

- Piquero, A. R., Schubert, C. A., & Brame, R. (2014). Comparing official and self-report records of offending across gender and race/ethnicity in a longitudinal study of serious youthful offenders. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 51(4), 526-556.

Objectives: Researchers have used both self-reports and official records to measure the prevalence and frequency of crime and delinquency. Few studies have compared longitudinally the validity of these two measures across gender and race/ethnicity in order to assess concordance.

Methods: Using data from the Pathways to Desistance, a longitudinal study of 1,354 serious youthful offenders, we compare official records of arrest and self-reports of arrest over seven years.

Results: Findings show moderate agreement between self-reports and official arrests, which is fairly stable over time and quite similar across both gender and race/ethnicity. We do not find any race differences in the prevalence of official arrests, but do observe a gender difference in official arrests that is not accounted for by self-reported arrests.

Conclusions: Further work on issues on the validity and reliability of different forms of offending data across demographic groups is needed., quite a bit below the 38% in NLSYddd

This is not a sample of normal people where we can evaluate self-report vs. other report, but an ‘elite’ criminal sample. It doesn’t find that people under-report arrests though, which one might suspect! This study agrees, with another sample of mentally ill people, and this study of criminals too. So maybe self-report is not that bad. After all, self-reported criminal activity correlates about the same with intelligence as does official records, suggesting not too much bias. I did a study myself on this in OKCupid data, and here’s another longitudinal study that agrees, even used IQ as well.

What about proper government statistics type studies with official arrest records? I found a few of these too:

- Mannuzza, S., Klein, R. G., & Moulton III, J. L. (2008). Lifetime criminality among boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a prospective follow-up study into adulthood using official arrest records. Psychiatry research, 160(3), 237-246.

This study investigates the relationship between childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and later criminality. White boys (n = 207, ages 6–12) with ADHD, free of conduct disorder, were assessed at ages 18 and 25 by clinicians who were blind to childhood status. A non-ADHD group served as comparisons. Lifetime arrest records were obtained when subjects were 38 years old for subjects who resided in New York State throughout the follow-up interval (93 probands, 93 comparisons). Significantly more ADHD probands than comparisons had been arrested (47% vs. 24%), convicted (42% vs. 14%), and incarcerated (15% vs. 1%). Rates of felonies and aggressive offenses also were significantly higher among probands. Importantly, the development of an antisocial or substance use disorder in adolescence completely explained the increased risk for subsequent criminality. Results suggest that even in the absence of comorbid conduct disorder in childhood, ADHD increases the risk for developing antisocial and substance use disorders in adolescence, which, in turn, increases the risk for criminal behavior in adolescence and adulthood.

Again, this is a select sample, but their control group at least provides some non-select comparison. Still, we get 24% for the White controls at age 38. We saw 29% in Add Health aged aged 24–34, and 38% in NLSY97 at age ages 18 and 23 but in older years. So about 30% is the overall finding.

What about register studies of the general population? I recently wrote about how bad psychotics are and the importance of anti-psychotics. One of these studies has arrest prevalence:

- Sariaslan, A., Leucht, S., Zetterqvist, J., Lichtenstein, P., & Fazel, S. (2021). Associations between individual antipsychotics and the risk of arrests and convictions of violent and other crime: a nationwide within-individual study of 74 925 persons. Psychological medicine, 1-9.

Background Individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorders who are prescribed antipsychotics have lower rates of violence and crime but the differential effects of specific antipsychotics are not known. We investigated associations between 10 specific antipsychotic medications and subsequent risks for a range of criminal outcomes.

Methods We identified 74 925 individuals who were ever prescribed antipsychotics between 2006 and 2013 using nationwide Swedish registries. We tested for five specific first-generation antipsychotics (levomepromazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, flupentixol, and zuclopenthixol) and five second-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole). The outcomes included violent, drug-related, and any criminal arrests and convictions. We conducted within-individual analyses using fixed-effects Poisson regression models that compared rates of outcomes between periods when each individual was either on or off medication to account for time-stable unmeasured confounders. All models were adjusted for age and concurrent mood stabilizer medications.

Results The relative risks of all crime outcomes were substantially reduced [range of adjusted rate ratios (aRRs): 0.50–0.67] during periods when the patients were prescribed antipsychotics v. periods when they were not. We found that clozapine (aRRs: 0.28–0.44), olanzapine (aRRs: 0.46–0.72), and risperidone (aRRs: 0.53–0.64) were associated with lower arrest and conviction risks than other antipsychotics, including quetiapine (aRRs: 0.68–0.84) and haloperidol (aRRs: 0.67–0.77). Long-acting injectables as a combined medication class were associated with lower risks of the outcomes but only risperidone was associated with lower risks of all six outcomes (aRRs: 0.33–0.69).

Conclusions There is heterogeneity in the associations between specific antipsychotics and subsequent arrests and convictions for any drug-related and violent crimes.

It only looked at arrests for violent crimes, not total arrests. I don’t know what the proportion is, but maybe 50%?

In Swedes who were born between 1961 and 1990 (n men = 2 240 557; n women = 2 128 205), we identified 37 565 (1.7%) men and 37 360 (1.8%) women who were prescribed with any antipsychotic between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2013. The baseline characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1 and the distribution of prescriptions of individual antipsychotics during the follow-up across patients with and without psychotic disorders are presented in Table 2. During the study period, 8815 men (23.5%) were arrested for 25 559 violent crimes, and 3271 women (8.8%) were arrested for 6719 violent crimes, in this cohort. The unadjusted rates for violent crime arrests and convictions were considerably lower during periods when the individuals were prescribed antipsychotics (9.7–34.1 events per 1000 person-years; Fig. 1A; Online Supplementary Table S2) as compared to periods when they were not (26.0–76.6 events per 1000 person-years; Fig. 1A; Online Supplementary Table S2). We found similar results for any and drug-related arrests, and when using convictions instead of arrests for all outcomes (Fig. 1A; Online Supplementary Table S2).

So we get 23.5% in this study period, these are mainly Swedish men. If we assume half of people were arrested for non-violent crimes, this would put the number at 47%! Too high! So I guess violent crime arrests are a large fraction of arrests. If we assume 2/3, then the number is about 35.25%. Not too far off the others. Maybe the Swedes keep better records.

What about a more extreme comparison group, say homeless people?

- Roy, L., Crocker, A. G., Nicholls, T. L., Latimer, E. A., & Ayllon, A. R. (2014). Criminal behavior and victimization among homeless individuals with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Psychiatric services, 65(6), 739-750.

Objectives The objectives of the systematic review were to estimate the prevalence and correlates of criminal behavior, contacts with the criminal justice system, and victimization among homeless adults with severe mental illness.

Methods MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Web of Science were searched for published empirical investigations of prevalence and correlates of criminal behavior, contacts with the justice system, and episodes of victimization in the target population.

Results The search yielded 21 studies. Fifteen examined prevalence of contacts with the criminal justice system; lifetime arrest rates ranged between 62.9% and 90.0%, lifetime conviction rates ranged between 28.1% and 80.0%, and lifetime incarceration rates ranged between 48.0% and 67.0%. Four studies examined self-reported criminal behavior, with 12-month rates ranging from 17.0% to 32.0%. Six studies examined the prevalence of victimization, with lifetime rates ranging between 73.7% and 87.0%. Significant correlates of criminal behavior and contacts with the justice system included criminal history, high perceived need for medical services, high intensity of mental health service use, young age, male gender, substance use, protracted homelessness, type of homelessness (street or shelter), and history of conduct disorder. Significant correlates of victimization included female gender, history of child abuse, and depression.

Conclusions Rates of criminal behavior, contacts with the criminal justice system, and victimization among homeless adults with severe mental illness are higher than among housed adults with severe mental illness.

So they are indeed much higher than our general samples. I didn’t find any more great Nordic register studies, maybe you can find some.

Finally, does this pass a sniff test? Do you know someone who has been arrested? I decided to try the usual approach to getting fast free data:

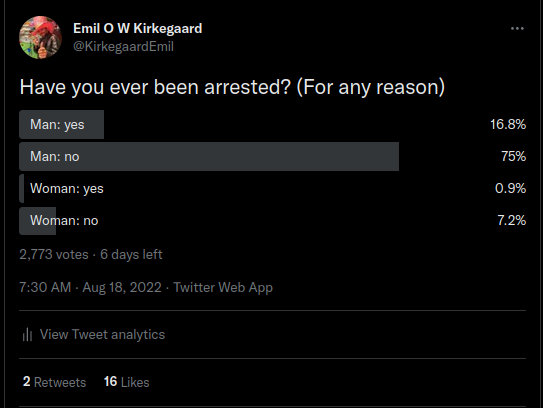

While I haven’t done the planned reader survey yet (post ideas in comments), it will no doubt show that survey takers are above average intelligence and social class, so arrest rates should be lower than average. They are also going to be relatively young, though not so young as to not be able to get arrested. Still, somewhat on the young side. I think Twitter self-selects for introverts, which I think will give a large negative effect. On the other hand, readers are going to be elevated in crimethink, so probably also crimebehavior, thus some positive selection. Overall, it seems we should expect somewhat lower values than the lifetime risks seen in the studies. A lot of people answered, n=2773, of which 2546 were men (92%). Of these, 18.3% of men had been arrested, and 11.1% of women. These numbers are quite a bit lower than the survey results, about 50% lower.

The answer then to my friend seems to be: you live in a low crime bubble! It seems that a lot of people have gotten arrested during their lifetime, and often for relatively trivial things, like drunk driving (to go to police station for blood testing), shoplifting, smoking weed, or public drunkenness/disorder.