I’ve been battling my way through round three of my COVID adventures this week, and it’s not been fun. 3 days of lying in bed with full body fever, cold sweat and constant coughing. Now the fever and cold sweat are over with but the coughing is driving me nuts. So what can one do about it? One common old housewives advice (DA: gammelt husråd) is to drink warm tea with honey. Honey is the way bees store energy, so presumably it needs a way to stay relatively free from microbes eating it, i.e., to be anti-microbial and anti-bacterial. I also guess that honey used to be kinda expensive to acquire, so one wouldn’t use it as medical treatment unless one really thought it would work. Whatever the origin and what prior we should assign to such advice, has it been tested? I expected the answer was no, but actually it has been tested a few times, and it seems legit. There are some popular science articles on the topic and even a Cochrane review (I think it’s bad!), but I’m going to disregard their summaries and go over the actual studies.

- Paul, I. M., Beiler, J., McMonagle, A., Shaffer, M. L., Duda, L., & Berlin, C. M. (2007). Effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and no treatment on nocturnal cough and sleep quality for coughing children and their parents. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 161(12), 1140-1146.

Objectives: To compare the effects of a single nocturnal dose of buckwheat honey or honey-flavored dextromethorphan (DM) with no treatment on nocturnal cough and sleep difficulty associated with childhood upper respiratory tract infections.

Design: A survey was administered to parents on 2 consecutive days, first on the day of presentation when no medication had been given the prior evening and then the next day when honey, honey-flavored DM, or no treatment had been given prior to bedtime according to a partially double-blinded randomization scheme.

Setting: A single, outpatient, general pediatric practice.

Participants: One hundred five children aged 2 to 18 years with upper respiratory tract infections, nocturnal symptoms, and illness duration of 7 days or less.

Intervention: A single dose of buckwheat honey, honey-flavored DM, or no treatment administered 30 minutes prior to bedtime.

Main outcome measures: Cough frequency, cough severity, bothersome nature of cough, and child and parent sleep quality.

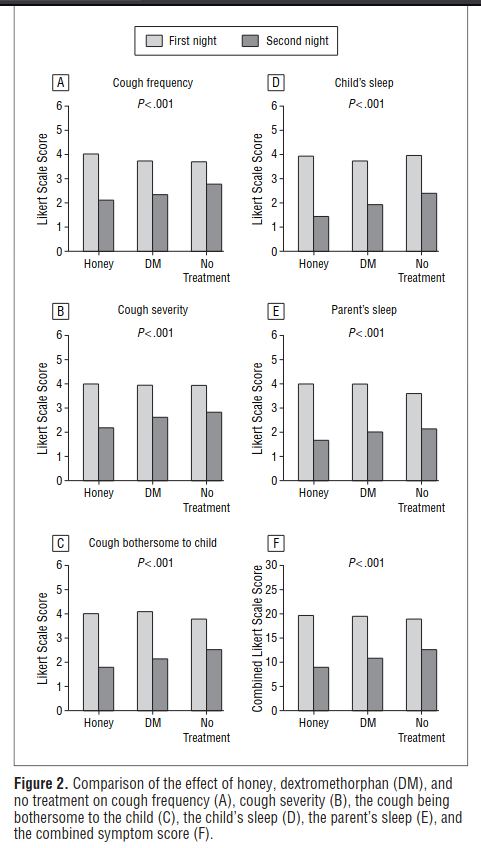

Results: Significant differences in symptom improvement were detected between treatment groups, with honey consistently scoring the best and no treatment scoring the worst. In paired comparisons, honey was significantly superior to no treatment for cough frequency and the combined score, but DM was not better than no treatment for any outcome. Comparison of honey with DM revealed no significant differences.

Conclusions: In a comparison of honey, DM, and no treatment, parents rated honey most favorably for symptomatic relief of their child’s nocturnal cough and sleep difficulty due to upper respiratory tract infection. Honey may be a preferable treatment for the cough and sleep difficulty associated with childhood upper respiratory tract infection.

Trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00127686.

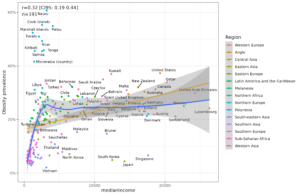

Results:

Looks reasonable. 3-way split as there are 2 treatment groups, the other being dextromethorphan (a standard drug, indeed a hallucinogen in large doses!). The p values are tiny, randomization looks OK. But the baseline data seems sketchy though:

Notice there are a lot of numbers that round to exactly .00, 5 in total, 4 in honey group. Seems unlikely but not a big red flag. Might fail a GRIM or SPRITE test or one of the related tests.

-

Shadkam, M. N., Mozaffari-Khosravi, H., & Mozayan, M. R. (2010). A comparison of the effect of honey, dextromethorphan, and diphenhydramine on nightly cough and sleep quality in children and their parents. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(7), 787-793.

Objectives: Coughing is a prevalent symptom of upper respiratory infections (URIs) that cause disturbance in the sleep of children and their parents. There is as yet no reliable treatment to control URIs and their related cough; however, drugs such as dextromethorphan (DM) and diphenhydramine (DPH) are now mainly used in the world. The aim of this study is to compare the effect of honey, DM, and DPH on the nightly cough and sleep quality of children and their parents.

Design: This was a clinical trial study in which 139 children aged 24-60 months suffering from coughing due to URIs were selected and assigned randomly to 4 groups. The first group received honey (HG), the second one DM (DMG), the third DPH (DPHG), but the fourth group or control group (CG) was assigned to a supportive treatment.

Outcome measures: After approximately a 24-hour intervention, the 4 groups were reexamined and their cough frequency, cough severity, and sleep quality in children and their parents were recorded by using the questionnaire with Likert-type questions.

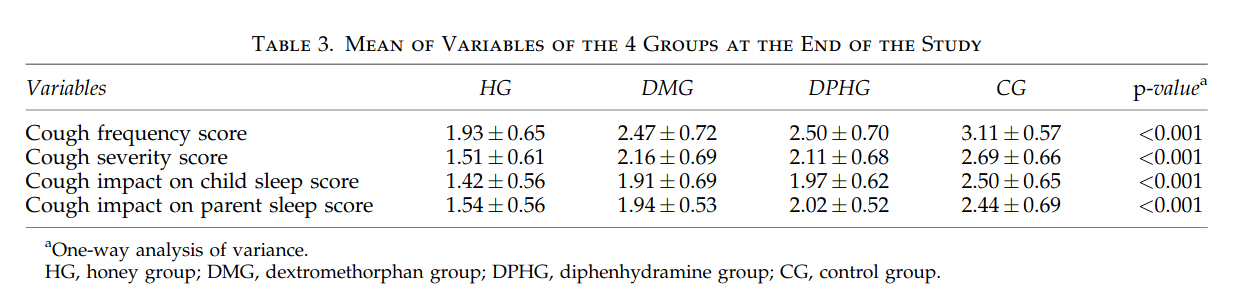

Results: The mean of cough frequency score HG is 4.09 +/- 0.72 and 1.93 +/- 0.65 before and after the intervention, respectively, while these figures for the CG are 4.11 +/- 0.78 and 3.11 +/- 0.57, respectively. After the intervention, the difference of the mean score of the variables in all groups became statistically significant. The mean score of all variables in HG has stood significantly higher than those in other groups. There is also a significant relationship between the DMG and CG groups, even though there is no statistically difference between DMG and DPHG groups.

Conclusions: The result of the study demonstrated that receiving a 2.5-mL dose of honey before sleep has a more alleviating effect on URIs-induced cough compared with DM and DPH doses.

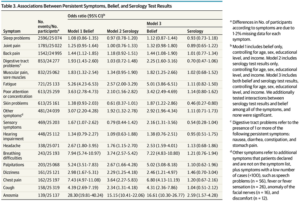

Their results are crystal clear:

So honey beats standard drugs (DMG & DPHG) and standard drugs beat placebo/nothing. In fact, the results are suspiciously good. Every single main result has p < .001 with sample sizes in the 30’s. Their post-hoc pairwise comparisons are very close to < .001 for every comparison the authors like, and p > .10 for the ones they don’t like. Given the sample size, this seems very unlikely.

The study is from Iran. We know to trust studies from such countries less, as they often show signs of fraud. Iran had the highest rate of scientific retractions in one study and was tied for first place for dishonesty in another study. So this one is hmm!

- Cohen, H. A., Rozen, J., Kristal, H., Laks, Y., Berkovitch, M., Uziel, Y., … & Efrat, H. (2012). Effect of honey on nocturnal cough and sleep quality: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Pediatrics, 130(3), 465-471.

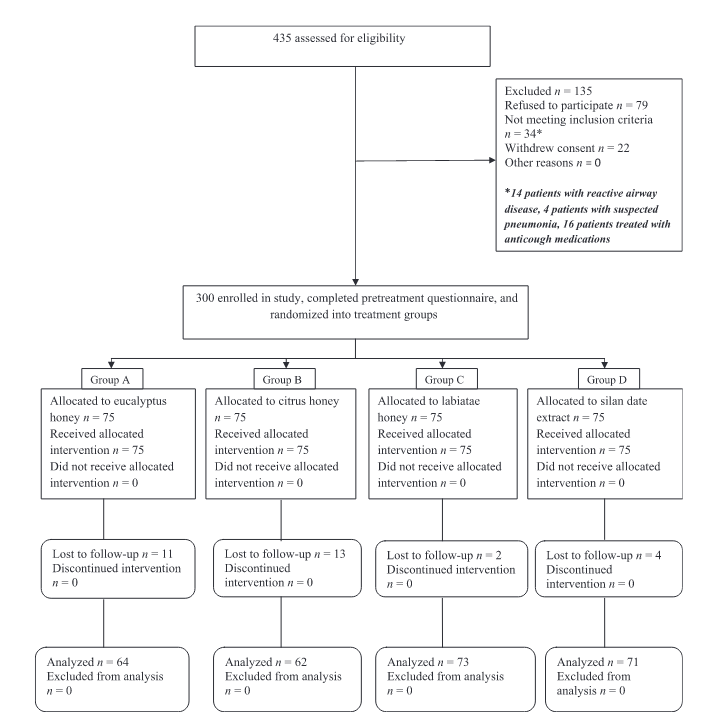

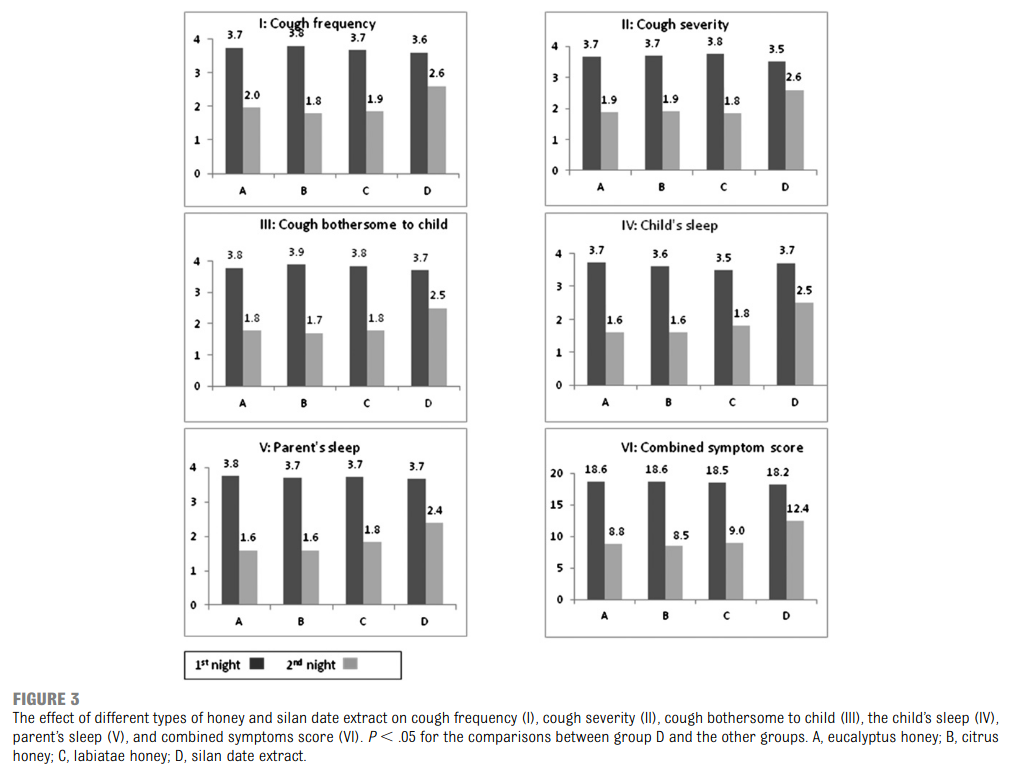

Objectives: To compare the effects of a single nocturnal dose of 3 honey products (eucalyptus honey, citrus honey, or labiatae honey) to placebo (silan date extract) on nocturnal cough and difficulty sleeping associated with childhood upper respiratory tract infections (URIs).

Methods: A survey was administered to parents on 2 consecutive days, first on the day of presentation, when no medication had been given the previous evening, and the following day, when the study preparation was given before bedtime, based on a double-blind randomization plan. Participants included 300 children aged 1 to 5 years with URIs, nocturnal cough, and illness duration of ≤ 7 days from 6 general pediatric community clinics. Eligible children received a single dose of 10 g of eucalyptus honey, citrus honey, labiatae honey, or placebo administered 30 minutes before bedtime. Main outcome measures were cough frequency, cough severity, bothersome nature of cough, and child and parent sleep quality.

Results: In all 3 honey products and the placebo group, there was a significant improvement from the night before treatment to the night of treatment. However, the improvement was greater in the honey groups for all the

Conclusions: Parents rated the honey products higher than the silan date extract for symptomatic relief of their children’s nocturnal cough and sleep difficulty due to URI. Honey may be a preferable treatment for cough and sleep difficulty associated with childhood URI.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01575821.

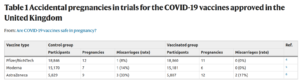

They had 3 honey groups:

Losses to follow-up is strangely high for a study of honey. Losses to follow-up are usually attributed to onerous demands of studies, or nasty side-effects that cause people to discontinue treatment. Results:

Pattern looks about the same as before. Authors don’t do any proper statistics. All their stats are those “p < .05” you see in the image above! A good approach would be a repeated measurement design, and one can collapse the honey treatments into a single group for more precision. Authors seem to have just done t-tests between groups. Nevertheless, the results are probably p < .01 if done correctly. In this case, getting the raw data would be useful for a reanalysis to give a better idea of how precise these results are. In fact, authors don’t even provide numerical results for the 2nd night, so I can’t recompute the stats.

-

Ahmadi, M., Moosavi, S. M., & Sh, Z. (2013). Comparison of the effect of honey and diphenhydramine on cough alleviation in 2-5-year-old children with viral upper respiratory tract infection. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences, 15(2), 8-13.

Background and Objective: Viral upper respiratory tract infection and cold drugs consumption is prevalent among children. These drugs have no effect on disease improvement, but it may also have accompanied with many side effects. This study was conducted to compare the effect of honey and diphehydramine on the alleviation of cough in 2-5-year-old children with viral upper respiratory tract infection. Materials and Methods: This double-blind clinical trial study was carried out on 170 children (60 boys and 66 girls) aged 2-5 years old with viral upper respiratory tract infection who were taken to the pediatric clinic of Shariatee hospital in Bandar Abbas, Iran during 2010. Children demographic charactrastics were including age, gender, period of illness, vaccination history, weight, growth, overall health, and cardiopulmonary examinations. Patients were randomly divided into two groups of 63 children receiving honey (three times a day and the last dose an hour before bed) and diphehydramine syrup (5mg/kg/BW). Two days later, subjects were examined again for the severity and frequency of coughs during day and night. Data were analyzed using SPSS-19, independent t-test and chi-square test. Results: Mean±SD of the age of children was 45.21±11.39 and 43.98±11.95 months in honey and diphenhydramine groups, respectively. The frequency and severity of night coughs was lower in the honey group (97.4%) as compared to the diphenhydramine group (58.7%) (P<0.02). The frequency and severity of daily coughs was lower in the honey group (84.1%) while it was lower in 58.7% of the diphenhydramine group (P<0.01). Conclusion: This study showed that honey is more effective than diphenhydramine in the alleviation of cough caused by viral URTI in 2-5-year-old children.

The study is written in Persian and doesn’t have any figures. But since it is comparing honey to a standard drug, and we suspect honey is about equally good or maybe slightly better, we don’t really expect much here to see. Their p value was .02, so eh. They didn’t use repeated measurement models, which they could have done to improve the precision. Probably this would reduce the p value to non-dodgy territory.

-

Waris, A., Macharia, W. M., Njeru, E. K., & Essajee, F. (2014). Randomised double blind study to compare effectiveness of honey, salbutamol and placebo in treatment of cough in children with common cold. East African medical journal, 91(2), 50-56.

Background: Acute upper respiratory infection is the most common childhood illness and presents with cough, coryza and fever. Available evidence suggests that cough medicines may be no more effective than honey-based cough remedies.

Objective: To compare effectiveness of honey, salbutamol and placebo in the treatment of cough in children with acute onset cough.

Design: Randomised control trial.

Setting: Aga Khan University Hospital Paediatric Casualty.

Subjects: Children between ages one to twelve years presenting with a common cold between December 2010 and February 2012 were enrolled.

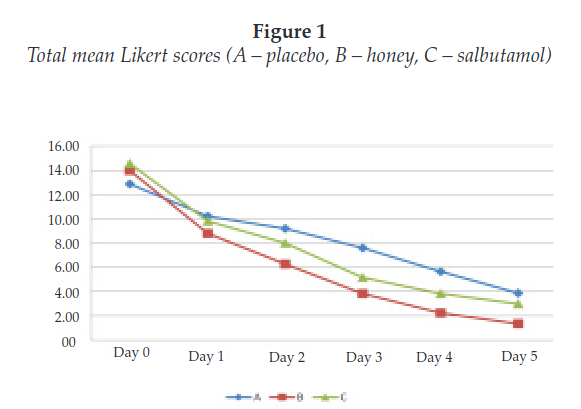

Outcome measures: Frequency, severity and extent to which cough bothered and disturbed child and parental sleep were assessed at baseline and over the subsequent five days through telephone interview using a validated scoring tool.

Results: One hundred and forty five children were enrolled in the study (45- placebo, 57 -honey, 43 -salbutamol). Of the 145 children 51% were male. Honey significantly reduced the total mean symptom score by day three (p < 0.001). Total mean difference in scores between day zero to five demonstrated a significant difference of honey’s efficacy over placebo (p < 0.002) however no difference was noted when compared to salbutamol (p < 0.478). Significant differences in both total as well as each individual symptom score was detected with honey consistently scoring the best whilst placebo and salbutamol scored the worst. In paired comparisons honey was superior to placebo but not salbutamol, whilst salbutamol was not superior to placebo.

Conclusion: Honey was most effective in symptomatic relief of symptoms associated with the common cold whilst salbutamol or placebo offered no benefit.

So an African, Kenyan, study. Results:

Looks solid. Their statistical analyses look good (repeated measures model). I don’t have any particular complaints. Their p values are normal looking for their various subgroup and post-hoc analyses.

- Sopo, S. M., Greco, M., Monaco, S., Varrasi, G., Di Lorenzo, G., & Simeone, G. (2015). Effect of multiple honey doses on non-specific acute cough in children. An open randomised study and literature review. Allergologia et immunopathologia, 43(5), 449-455.

Background: Honey is recommended for non-specific acute paediatric cough by the Australian guidelines. Current available randomised clinical trials evaluated the effects of a single evening dose of honey, but multiple doses outcomes have never been studied.

Objectives: To evaluate the effects of wildflower honey, given for three subsequent evenings, on non-specific acute paediatric cough, compared to dextromethorphan (DM) and levodropropizine (LDP), which are the most prescribed over-the-counter (OTC) antitussives in Italy.

Methods: 134 children suffering from non-specific acute cough were randomised to receive for three subsequent evenings a mixture of milk (90ml) and wildflower honey (10ml) or a dose of DM or LDP adjusted for the specific age. The effectiveness was evaluated by a cough questionnaire answered by parents. Primary end-point efficacy was therapeutic success. The latter was defined as a decrease in cough questionnaire score greater than 50% after treatment compared with baseline values.

Results: Three children were excluded from the study, as their parents did not complete the questionnaire. Therapeutic success was achieved by 80% in the honey and milk group and 87% in OTC medication group (p=0.25).

Conclusions: Milk and honey mixture seems to be at least as effective as DM or LDP in non-specific acute cough in children. These results are in line with previous studies, which reported the health effects of honey on paediatric cough, even if placebo effect cannot be totally excluded.

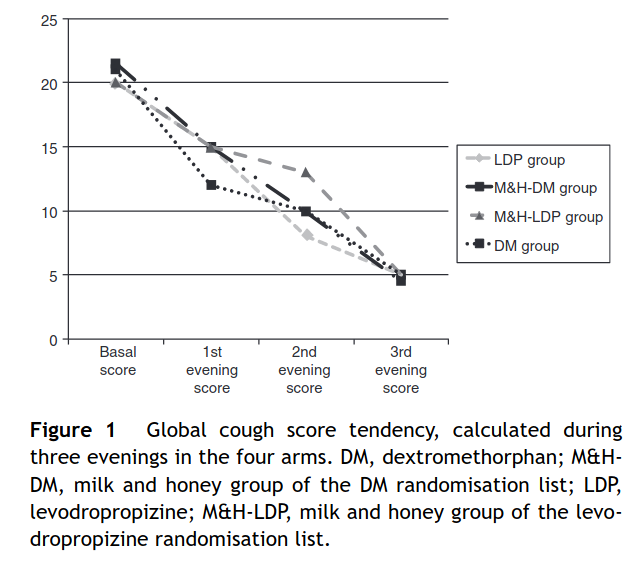

Results:

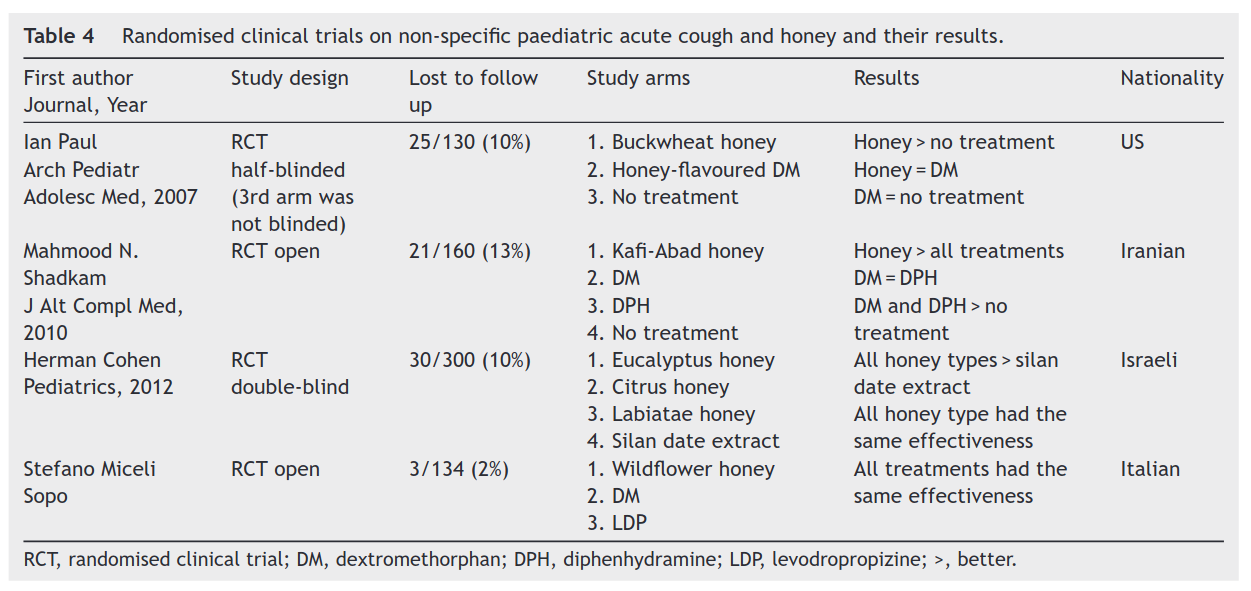

Their design is complicated, as they have 4 groups, 2×2 combinations of normal drugs (DM and LDP) which may or may not be combined with milk and honey (M&H). Their study is too small for this kind of thing I think, but that’s typical of basically all science. Their results don’t really show anything. Since they lack a control group, this study cannot tell us whether honey works compared with nothing, just that their 3 treatments seemed to work about equally well. The authors also helpfully provide a mini-literature review in a table:

- Gupta, A., Gaikwad, V., Kumar, S., Srivastava, R., & Sastry, J. L. N. (2016). Clinical validation of efficacy and safety of herbal cough formulation “Honitus syrup” for symptomatic relief of acute non-productive cough and throat irritation. Ayu, 37(3-4), 206.

Materials and Methods:

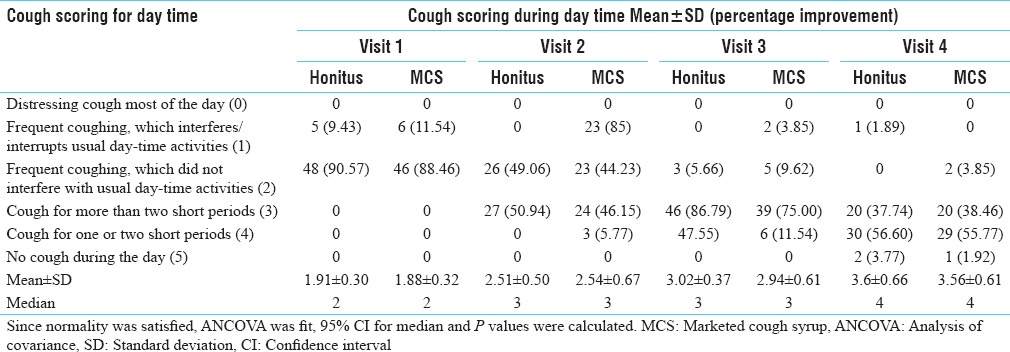

This was a randomized double-blind study conducted in 105 individuals who received orally 2 tsp (10 ml) of either Honitus or marketed cough syrup (MCS) four times a day for 3 days. Response to treatment was evaluated from baseline to the end of treatment period on the basis of changes in day and night frequencies of cough, throat irritation and development of adverse events (AEs).

Results:

Honitus was found safe and effective in reducing symptoms of acute nonproductive cough, throat irritation, and comparable to MCS in reducing day and night frequencies of cough, the time to relief from cough and throat irritation and the Physician’s Global Assessment of cough. Honitus showed comparably better results than MCS on throat irritation, the duration of relief from cough and throat irritation without causing drowsiness. No AEs related to study or study products were reported.

Conclusion:

Honitus Syrup is safe and effective in reducing the symptoms of acute nonproductive cough and throat irritation without causing drowsiness.

An Indian study done by a pharma company marketing its own drug. They say it was analyzed blindly etc., but who knows. They find that honey works better than ‘marketed cough syrup’. What is that?

Honitus Cough Syrup (Mfd by Dabur India Limited) is an Ayurvedic proprietary formulation comprising extracts of herbal ingredients such as Tulsi (O. sanctum, Lf.), Yashti (G. glabra, Rt.), Kantakari (Solanum xanthocarpum, Pl.), Banaphsa (V. odorata, Aerial.), Shunthi (Z. officinale, Rz.), Pippali (P. longum, Fr.), Vasa (A. vasica, Lf.), Shati (Hedychium spicatum, Rz.) and honey. Batch: BD0344 of Honitus was used in the present study.

MCS contained diphenhydramine, ammonium chloride and sodium citrate as active ingredients.

The authors say their study is inspired by old Indian religious stuff, so eh. It’s some mix of herbs in honey. The results in one table:

The results look impossible. Notice in visit 2, there are now too many people listed in the MCS group, as there are 23 people in category (1) and (2). In any case, their own means don’t show any improvement here. There are in fact numerous other similar errors with their tables. This looks like it was quickly done by high school students, and given a bad grade. I wouldn’t trust anything about this study.

-

Seçilmiş, Y., & Silici, S. (2020). Bee product efficacy in children with upper respiratory tract infections. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 62(4), 634-640.

Background and objectives. The most common infectious disease in children is acute upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Many drugs, especially antitussive drugs, are used for symptomatic treatment. Bee products (propolis, royal jelly, and honey) have antiviral, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties, and they have synergistic effects with antibiotics. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a mixture of bee products in URTI in children.

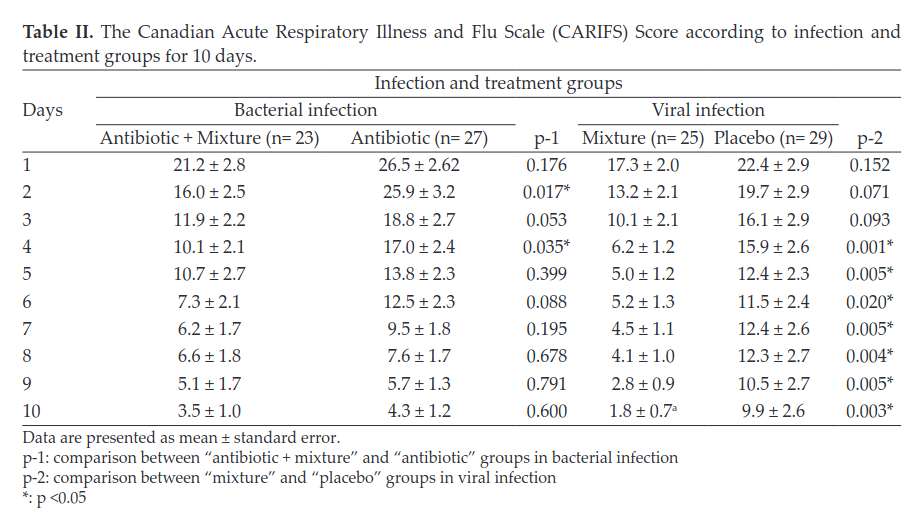

Methods. The patients were divided into four groups consisting of two bacterial groups receiving either antibiotics or antibiotics + bee products and two viral groups treated with either placebo or bee products. Disease severity and improvement duration were assessed by the Canadian Acute Respiratory Illness and Flu Scale (CARIFS) Score.

Results. One hundred and four patients (59 male, 56.7%; 45 female, 43.3%) aged between 5‒12 years were included in the study. Fifty patients (48%) were evaluated for bacterial infections and 54 (52%) for viral infections. Patients with viral infection receiving a mixture product showed earlier improvement, compared to placebo group. CARIFS scores were significantly lower in antibiotic + mixture group on day-2 and day-4, compared to antibiotic alone group (p <0.05). None of the patients developed any reactions or side effects to the mixture product.

Conclusions. Bee products are effective in symptomatic treatment of upper respiratory tract infections. Bee products can be considered as a good treatment option because the available drugs already used for symptomatic treatment are not cost effective and can also have serious side effects in children.

So a Turkish study, not exactly about coughing but upper respiratory tract infections, which I take to be just about the same thing. You could cough from lung cancer but these studies presumably don’t include lung cancer patients. Their ‘bee product’ combination with anti-biotic did better than just anti-biotics. Results:

So basically honey, I mean bee products, work clearly against viral infections. They probably work against bacterial infections (p values .017, .053, .035, .088) but evidence wasn’t totally clear.

Conclusions

There’s a bunch of studies from around the world which all find reasonably consistent conclusions. Some of these are by 3rd worlders with dodgy looking results, but the other ones look OK. Given how cheap and safe honey is, I can’t see any reason not to take it for coughing. I mean, I wouldn’t say it’s 100% certain that honey works against coughing, but based on this evidence, probably it’s 90% certain. Old housewives seem to be right!