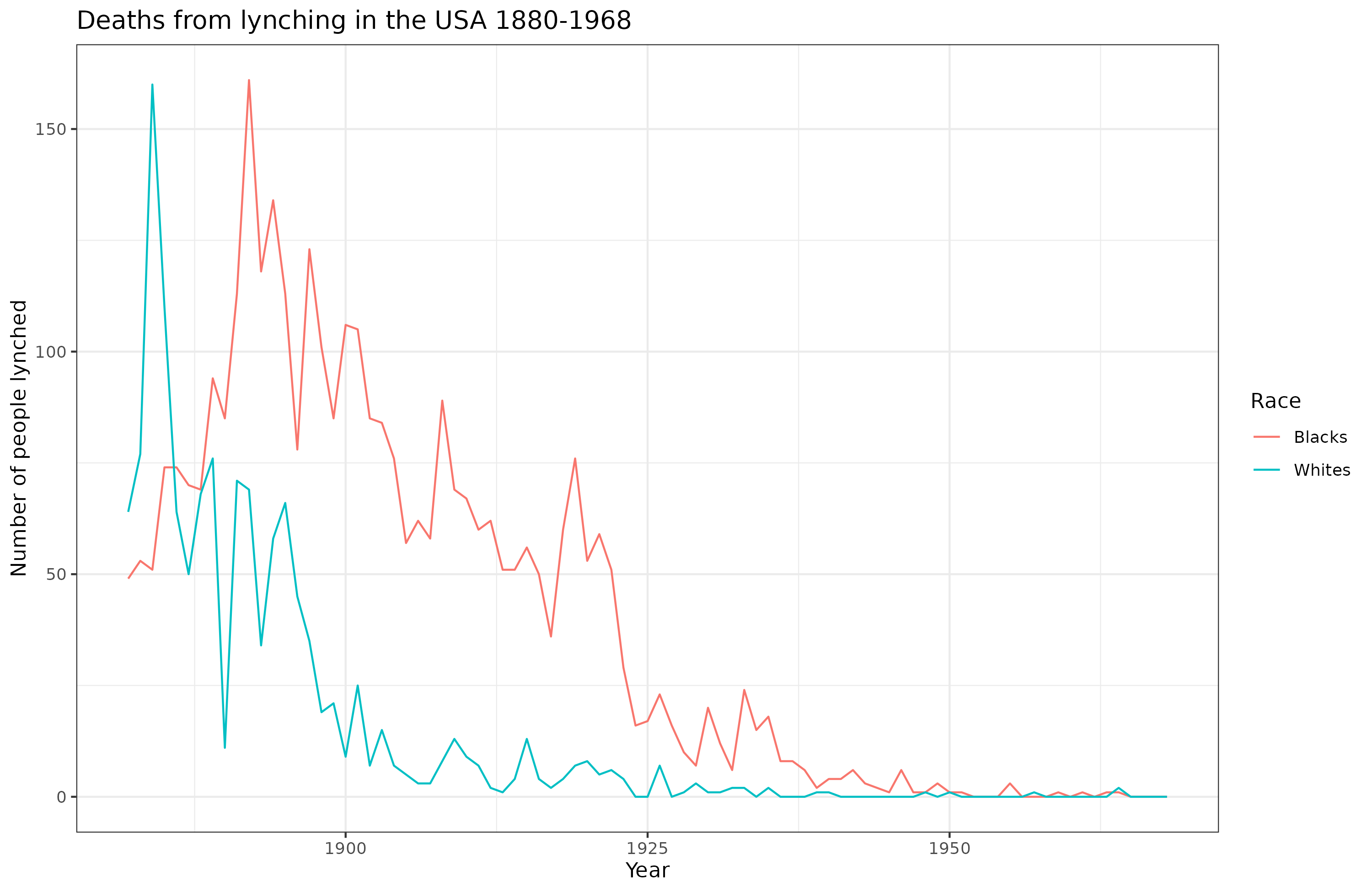

Let’s apply some cool headed thinking to the issue. In societies without well-functioning legal systems, residents will strive to achieve their own justice. Usually, this works by appointing someone to administer justice, the sheriff. However, in more rural areas, there weren’t even reliable sheriffs around. So a mob will form and deliver what own justice, and it may not always be fair and right. The various pro-African groups in USA has compiled statistics on the number of people who were lynched (Tuskegee Institute):

Tuskegee University now houses the nation’s most complete record of lynchings occurring in the U.S. during an 86-year period spanning 1882 to 1968. During this time, 4,743 people were lynched — including 3,446 African Americans and 1,297 whites.

The disproportionate numbers of Blacks is to be expected given their higher violent crime rate. Here’s the crimes people were accused of (same source):

38% of victims of lynching were accused of murder, 16% of rape, 7% for attempted rape, 6% were accused of felonious assault, 7% for theft, 2% for insult to white people, and 24% were accused of miscellaneous offenses or no offense.

We know mob justice to be fairly unreliable. But how unreliable? Somehow Wikipedia still mentions some research on this:

In 1940, sociologist Arthur F. Raper investigated one hundred lynchings after 1929 and estimated that approximately one-third of the victims were falsely accused.[25]

The actual source, though, is: Gunnar Myrdal’s (1944). An American Dilemma, p. 561. We can look it up and see what he had to say:

Lynching is spectacular and has attracted a good deal of popular and scientific8 attention. It is one Southern pattern which has continued to arouse disgust and reaction in the North and has, therefore, been made much of by Negro publicists. It should not be forgotten, however, that lynching is just one type of extra-legal violence in a whole range of types that exist in the South. The other types, which were considered earlier in this chapter are much more common than lynching and their bad effects on white morals and Negro security are greater.7

Lynchings were becoming common in the South in the ‘thirties, ‘forties and ‘fifties of the nineteenth century. Most of the victims in this early period were white men. The pattern of lynching Negroes became set during Reconstruction. No reliable statistics before 1889 are available. Between 1889 and 1940, according to Tuskegee Institute figures, 3,833 people were lynched, about four-fifths of whom were Negroes. The Southern states account for nine-tenths of the lynchings. More than two-thirds of the remaining one-tenth occurred in the six states which immediately border the South: Maryland, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Kansas. Since the early 189o’s, the trend has been toward fewer and fewer lynchings. The annual average in the ‘nineties was near 200; in the ‘thirties it dropped to slightly over 10. In 1941 it was down to 4, but there are already more than this in 1942 (July). The decrease has been faster outside the South, and the lynching of whites has dropped much more than that of Negroes. Lynching has become, therefore, more and more a Southern phenomenon and a racial one. Against the decrease in number of victims there has been a marked trend toward greatly aggravated brutality, extending to torture, mutilation and other sadistic excesses.8

Lynching is a rural and small town custom and occurs most commonly in poor districts.9 There are some indications that lynchings go in waves and tend to recur in the same districts.w The accusations against persons lynched during the period for which there are records were: in 38 per cent of the cases for homicide, 6 per cent for felonious assault, 16 per cent for rape, 7 per cent for attempted rape, 7 per cent for theft, 2 per cent for insult to white persons and 24 per cent for miscellaneous offenses or no offense at all.11 In the last category arc all sorts of irritations: testifying at court against a white man or bringing suit against him, refusal to pay a note, seeking employment out of place, offensive language or boastful remarks.12 Regarding the accusations for crime, Raper testifies: “Case studies of nearly one hundred lynchings since 1929 convince the writer that around a third of the victims were falsely accused.” The meaning of these facts is that, in principle, a lynching is not merely a punishment against an individual but a disciplinary device against the Negro group.b

The danger of Negroes’ desire to rape white women has acquired a special and strategic position in the defense of the lynching practice.c Actually, only 23 per cent of the victims were accused of raping or attempting to rape. There is much reason to believe that this figure has been inflated by the fact that a mob which makes the accusation of rape is secure against any further investigation; by the broad Southern definition of rape to include all sex relations between Negro men and white women; and by the psychopathic fears of white women in their contacts with Negro men. The causes of lynching must, therefore, be sought outside the Southern rationalization of “protecting white womanhood.”

This does not mean that sex, in a subtler sense, is not a background factor in lynching. The South has an obsession with sex which helps to make this region quite irrational in dealing with Negroes generally. In a special sense, too, as William Archer, Thomas P. Bailey, and Sir Harry Johnston early pointed out,18 lynching is a way of punishing Negroes for the white Southerners’ own guilt feelings in violating Negro women, or for presumed Negro sexual superiority. The dullness and insecurity of rural Southern life, as well as the eminence of emotional puritanical religion, also create an emphasis upon sex in the South which especially affects adolescent, unmarried, and climacteric women, who are inclined to give significance to innocent incidents. The atmosphere around lynching is astonishingly like that of the tragic phenomenon of “witch hunting” which disgraced early Protestantism in so many countries. The sadistic elements in most lynchings also point to a close relation between lynching and thwarted sexual urges.111

Lynching is a local community affair. The state authorities usually do not side with the lynchers. They often try to prevent lynchings but seldom take active steps to punish the guilty. This is explainable in view of the tight hold an the courts by local public opinion. The lynchers are seldom indicted by a grand jury. Even more seldom arc they sentenced, since the judge, the prosecutor, the jurors, and the witnesses are either in sympathy with the lynchers or, in any case, do not want to press the case. If sentenced, they are usually pardoned.10 While the state police can be used to prevent lynching, the local police often support the lynching. From his study of 100 lynchings since 1929, Raper estimates that “… at least one- half of the lynchings are carried out with police officers participating, and that in nine-tenths of the others the officers either condone or wink at the mob action.”7

The actual participants in the lynching mobs usually belong to the frustrated lower strata of Southern whites.18 Occasionally, however, the people of the middle and upper classes take part, and generally they condone the deed, and nearly always they find it advisable to let the incident pass without assisting in bringing the guilty before the court.11 Women and children are not absent from lynching mobs; indeed, women sometimes incite the mobs into action.20

Myrdal goes on to speculate about the psychopathology of lynching.

The footnote for the Raper study (unfortunate name!) is:

Arthur Raper, “Race and Class Pressures,” unpublished manuscript prepared for thi1 study (1940), p. 274. Raper adds that it is his” . opinion that a great contribution could be made by some arrangement for immediate factual newspaper reports on each lynching and other race and class violence by trained new&paper men. At present the local representative of the news-gathering agencies sends in the story and usually says about what the community wants said. Expert reporters who could be sent wherever a mob threatened would be free to present the facts in the case.” (Ibid., pp. 274-275.)

The study appears never to have been published. I don’t see any other studies of this either. Almost everything academic on the topic is activism against lynching or various moaning pieces. I get it, mob justice is a bad system. Yes, some innocent people were killed, yes, a lot of these people were Black. Nevertheless, from a historical perspective and comparative justice interest, it is interesting to know how guilty the victims were. Indeed, calling them “victims” without qualification is misleading as many of these crimes would have come with a death penalty anyway. Jurij’s speculation that 90% were guilty is perhaps too high, but the only source we have said that about 33% were falsely accused, so 67% were guilty. Wikipedia gives an example (George Meadows):

On January 14, 1889, a white woman reported that she had been raped and her son killed by an African American man.[2] Over 400 white coal miners formed themselves into groups and brought several black men to the woman, who was unable to identify any of them as the alleged criminal. The next day, the miners brought Meadows, a new arrival to the area, and after a brief investigation, determined him to be guilty.[2] The woman begged the mob not to lynch Meadows, as she was unsure if he was the criminal, but the mob went forward with the lynching and killed him near the Pratt Mines. Following his death, his body was shot multiple times and left in public view by an undertaker. Meadows was later buried in a paupers’ grave in what is now Lane Park in Birmingham, Alabama.[3]

On January 16, the sheriff decided that Meadows was not the actual perpetrator of the crime, and arrested another African American man, Lewis Jackson.[3]

On the other hand, many of the cases were like that of Jesse Washington:

Jesse Washington was a seventeen-year-old African American farmhand who was lynched in the county seat of Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916, in what became a well-known example of racist lynching. Washington was convicted of raping and murdering Lucy Fryer, the wife of his white employer in rural Robinson, Texas. He was chained by his neck and dragged out of the county court by observers. He was then paraded through the street, all while being stabbed and beaten, before being held down and castrated. He was then lynched in front of Waco’s city hall.

Over 10,000 spectators, including city officials and police, gathered to watch the attack. There was a celebratory atmosphere among whites at the spectacle of the murder, and many children attended during their lunch hour. Members of the mob cut off his fingers, and hung him over a bonfire after saturating him with coal oil. He was repeatedly lowered and raised over the fire for about two hours. After the fire was extinguished, his charred torso was dragged through the town. A professional photographer took pictures as the event unfolded, providing rare imagery of a lynching in progress. The pictures were printed and sold as postcards in Waco.

In his case, it wasn’t even mob justice, per se, as he was convicted of rape and murder in some kind of trial, but the punishment was delivered by the mob.

What about the modern false conviction rate? A probably politically correct study in PNAS studied death row inmates, and estimated about 4% were falsely convicted. That’s regrettable but much better than the 33% lynch mobs achieved.

I don’t want to say that lynching was mostly good and proper, but I want to say that the evil of lynching is far overestimated. Here’s the numbers everybody is citing:

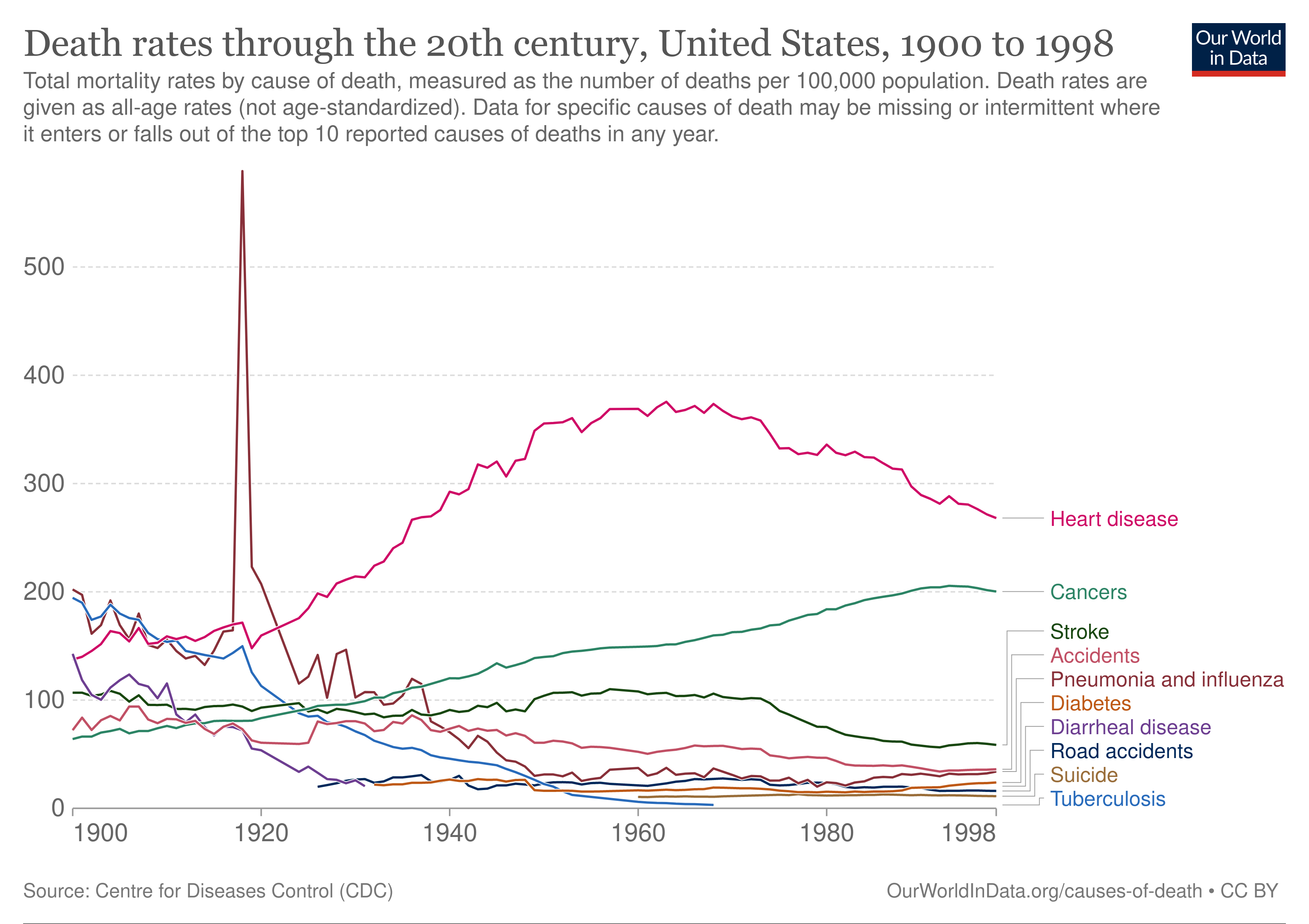

A total of a mere 4,740 people over 87 years of recorded data. Clearly, it used to be more popular, so there are some people who died before records began in 1880, we can say multiply the total by 50% to adjust for this recording bias, bringing us to 7,110. Is that a lot? The annual number of people dying in 1900 in the USA was about 1,300,000 people (GPT4). If we use the year with the most lynchings, 1892 with 230 killed, this comes out to a proportion of 0.000177 or 0.0177%. In the grand scheme of things, then, lynching was basically an unimportant, southern practice. Recall, back in 1900, hundreds of thousands of people died every year from a variety of preventable causes:

There were about 76 million people in USA in 1900, so the number of people dying in 1900 from the above causes are:

- Pneumonia and influenza: (202/100000) * 76000000 = 153,520

- Tuberculosis: 147,744

- Diarrheal diseases: 108,452

- Heart disease: 104,424

- Stroke: 81,244

- Accidents: 54,948

- Cancers: 48,640

- Lynching: 115

Even the smallest cause of the above is many times the total number of people ever lynched every year. There is little reason to be obsessed about this issue, even back in 1900. There is even less reason today.