There is idealized science and there is real life science. In idealized science, disinterested, smart, rational agents attempt to figure out how reality works out of sheer curiosity. They collaborate with one another to guard against whatever individual biases may affect results, results are reported honestly, and people help each other to work out flaws in studies. Over time, ideas are suggested, tested, and some are found to be useful, and the rest are discarded. Progress is made.

In reality land, science deviates from every aspect of this. The agents aren’t always terrible smart, they are certainly not disinterested, sometimes not very rational either. The goal isn’t merely to rescue us from ignorance, but to push people’s own careers and political ideologies. Studies are not replicated by 3rd parties, and if they are, often results are tinkered with in order to obtain something one can publish (that is, a small p value). Findings are couched in palatable egalitarian ideology, when results don’t fit the narrative so well.

One way to measure how far real science, say, psychology, is from ideal science is to do large-scale replication studies. With these, a bunch of studies are systematically redone to see if one can obtain similar results the second time around. The latest of these kinds of studies has just been posted as a preprint. The good news is that it found very similar results to the prior large-scale replication studies. The bad news is that the news are not very positive for actual science.

- Boyce, V., Mathur, M., & Frank, M. C. (2023). Eleven years of student replication projects provide evidence on the correlates of replicability in psychology.

Cumulative scientific progress requires empirical results that are robust enough to support theory construction and extension. Yet in psychology, some prominent findings have failed to replicate, and large-scale studies suggest replicability issues are widespread. The identification of predictors of replication success is limited by the difficulty of conducting large samples of independent replication experiments, however: most investigations re-analyse the same set of ~170 replications. We introduce a new dataset of 176 replications from students in a graduate-level methods course. Replication results were judged to be successful in 49% of replications; of the 136 where effect sizes could be numerically compared, 46% had point estimates within the prediction interval of the original outcome (versus the expected 95%). Larger original effect sizes and within-participants designs were especially related to replication success. Our results indicate that, consistent with prior reports, the robustness of the psychology literature is low enough to limit cumulative progress by student investigators.

That’s a lot of replications. The authors explain how this large number came about:

PSYCH 251 is a graduate-level experimental methods class in experimental psychology taught at Stanford University. During the 10 week class, each student replicates a published finding. They individually re-implement the study, write analysis code, pre-register their study, collect data (typically using an online crowd-sourcing platform), and write a structured replication report. Students in the course are free to choose studies related to their research interests, with the default recommendation being an article from a recent year of Psychological Science.

So, in other words, relatively elite graduate students at Stanford tried redid recently reported findings from a ‘high ranking’ (i.e. popular) journal. If peer reviewing and prestige works as it should, the work that gets published in such outlets should be particularly good. However, the results look like this:

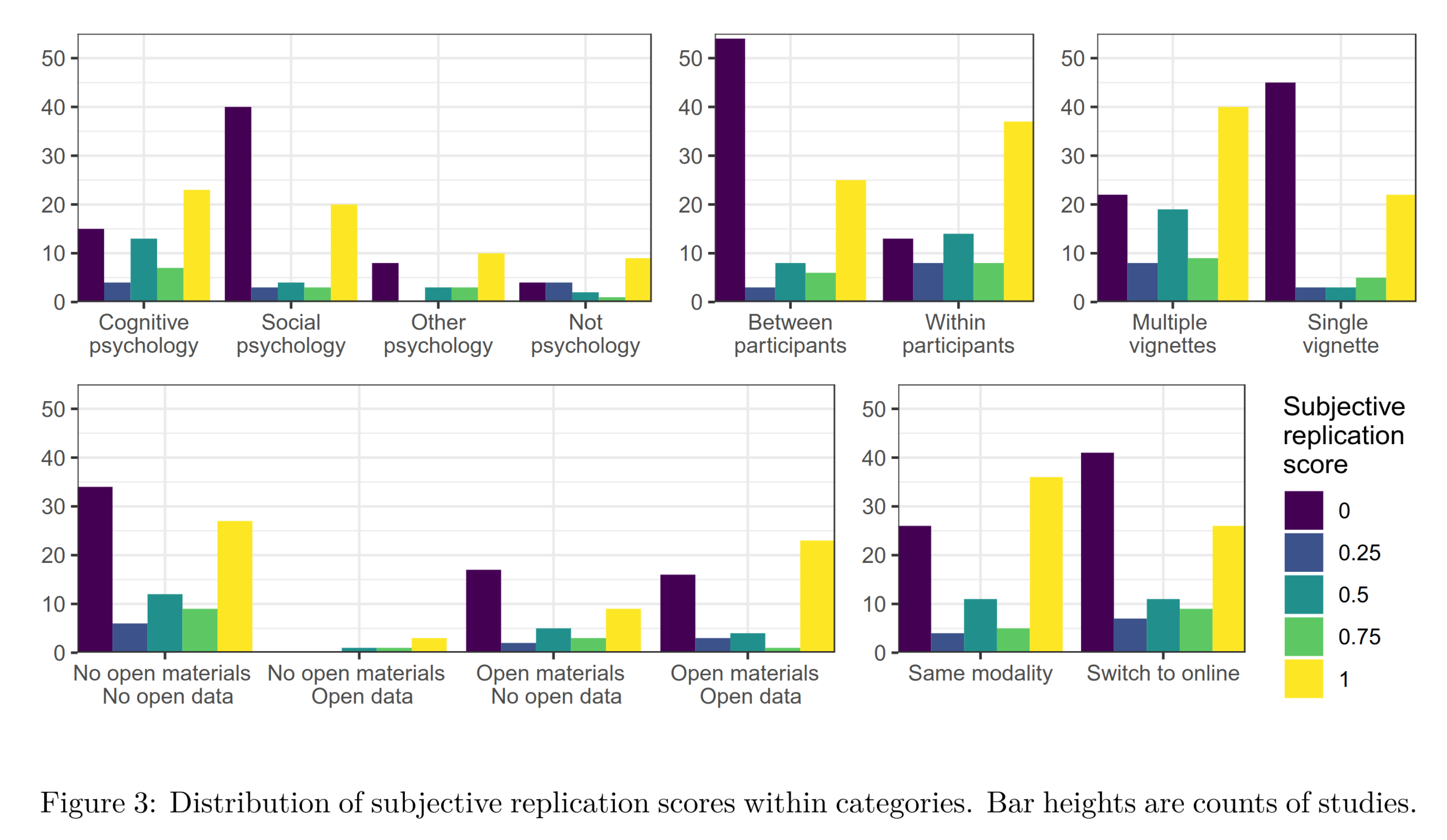

Each replication study was rated by 2 independent people about whether it supported the original study or not, on a 0-1 scale in increment of 0.25. The overall results are fairly abysmal. Only about half of the findings could be verified in a replication attempt. The authors also looked at which factors are associated with being a good study, i.e., that can be independently verified:

This isn’t the best way to analyze the data (why use Pearson correlation instead of beta regression?). There is only one reliable marker of being a good study according to these results: using a within-person design. These are studies where a subject is measured multiple times, and in between that there is some experimental intervention. This might be exposure to a TV news segment vs. children’s cartoon show, or reading a study summary about genetics vs. early educational interventions. Methodologists frequently recommend this study design, but it is often not feasible. Most studies in real life psychology use a between-person design where subjects are measured once.

The markers of being a bad study are: 1) having only one stimulus per study (I don’t know what this means exactly either), and more amusingly, 2) NOT being social psychology. Social psychology is the poster child for terrible science. Extremely politically biased and abysmal replication rates. It spawned the social priming which has been thoroughly discredited at this point, but which will certainly linger on for some decades until they get a new bad idea to promote, grit, growth mindset, power posing — take your pick. It’s like people with particularly poor ideas of how humans work self-select into this field.

There is some very tentative evidence that studies with open datasets are more likely to replicate well, but with p = .047, this is not something to get excited about.

Not mentioned in the findings above, for some reason, is that the effect size in the original study is also a good predictor. Studies that report small, finicky effects are more likely to reflect cheating with the statistics (p-hacking), or some small bias in the study that went unaccounted for somehow. Solid studies should show large effects with small p values.

One might object to these results that graduate students are maybe incompetent, and that’s why the replications didn’t work out so well. But this won’t work because the many prior large-scale replication studies were done by senior researchers, and they found just about the same results (i.e., about 50% success rate). Basically, this research and the prior research shows that a naive reading of mainstream science articles is like tossing a coin. Heads and the study probably is onto something (maybe not what the authors said, but at least something is there); tails and it was just noise dressed up in a paper. Who wants to read science under these conditions? Imagine if physics and engineering worked the same way. Bridges would randomly collapse half the time, planes would crash, ships sink. It would be an obvious failure to everyone, and something would be done about it. When psychology studies fail, luckily (?), most of the time nothing happens. But sometimes, research is used to justify social policies. When these are based on terrible science, these policies won’t work. If we are lucky, they will mainly waste time and money. If we are not lucky, they will have a negative effect (e.g. trigger warnings seem to just promote more PTSD).

For instance, growth mindset stuff has been aggressively promoted for the last decade or so. Here’s a new meta-analysis of growth mindset studies:

-

Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2023). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3-4), 133–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000352

According to mindset theory, students who believe their personal characteristics can change—that is, those who hold a growth mindset—will achieve more than students who believe their characteristics are fixed. Proponents of the theory have developed interventions to influence students’ mindsets, claiming that these interventions lead to large gains in academic achievement. Despite their popularity, the evidence for growth mindset intervention benefits has not been systematically evaluated considering both the quantity and quality of the evidence. Here, we provide such a review by (a) evaluating empirical studies’ adherence to a set of best practices essential for drawing causal conclusions and (b) conducting three meta-analyses. When examining all studies (63 studies, N = 97,672), we found major shortcomings in study design, analysis, and reporting, and suggestions of researcher and publication bias: Authors with a financial incentive to report positive findings published significantly larger effects than authors without this incentive. Across all studies, we observed a small overall effect: d¯ = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.09], which was nonsignificant after correcting for potential publication bias. No theoretically meaningful moderators were significant. When examining only studies demonstrating the intervention influenced students’ mindsets as intended (13 studies, N = 18,355), the effect was nonsignificant: d¯ = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.10]. When examining the highest-quality evidence (6 studies, N = 13,571), the effect was nonsignificant: d¯ = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.06, 0.10]. We conclude that apparent effects of growth mindset interventions on academic achievement are likely attributable to inadequate study design, reporting flaws, and bias. (PsycInfo Database Record (c) 2023 APA, all rights reserved)

Basically, it’s an expensive nothing-burger. Googling growth mindset + policy reveals a plethora of campaigns to implement this in primary schools and businesses. This efforts will be in vain and you will be paying for it.

The big question is: can psychology become a proper science in the future? What needs to be done? Honestly, my best idea is to design AIs that read all science, and tell us which studies are shit and which ones are good. To prevent bias, the AI will be strictly trained on objective data from large-scale replication studies like this new one. Otherwise, they are going to work just as well as the various “fact checker” websites that already exist.