Back in 1982 Richard Dawkins wrote a book called The Extended Phenotype, which argued that the “phenotype should not be limited to biological processes such as protein biosynthesis or tissue growth, but extended to include all effects that a gene has on its environment, inside or outside the body of the individual organism”. In layman’s terms, the phenotype is the presentation of some organism, that is, what actually exists. This contrasts with the genotype, which in this context means the genome (entire set of variants of some organism). One could also then talk about the envirotype, which doesn’t seem to be used much. Dawkins was talking about extending our thinking about what genes produce, aside from strictly speaking the organism — its amino acids, molecules, cells, organs — but also its behavior and the things the behavior results in, external to the organism. The go-to example is the beaver dam. Beaver dams are not made of beaver cells, but mainly dead cells of other organisms. Nevertheless, we know that beavers produce them, and variation in dams will surely reflect variations in beaver genetics. As such, the beaver dam is an extended phenotype of the beaver. Beavers are genetically programmed, or inclined if you wish, to produce dam-like structures. In their natural habitat, this results in the usual wooden structures. But given an unnatural habitat, it can result in this:

Clearly, this is a kind of malfunction of the beaver’s behavior, but a harmless and amusing one.

A new paper is about taking this line of thought to its logical conclusions when it comes to humans:

- Baumard, N., Fitouchi, L., André, J. B., Nettle, D., & Scott-Philipps, T. (2023). The gene’s-eye view of culture: vehicles, not replicators.

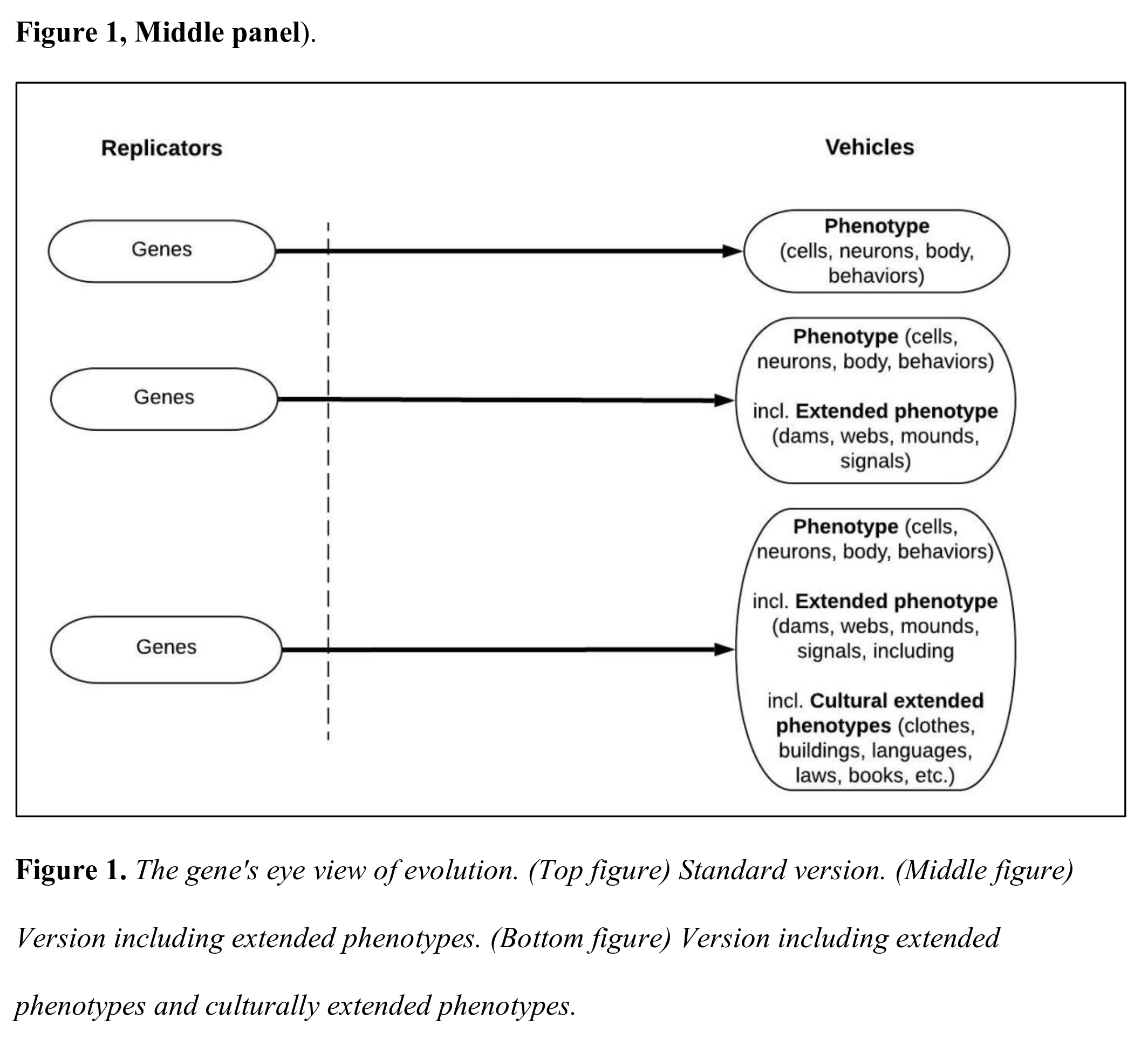

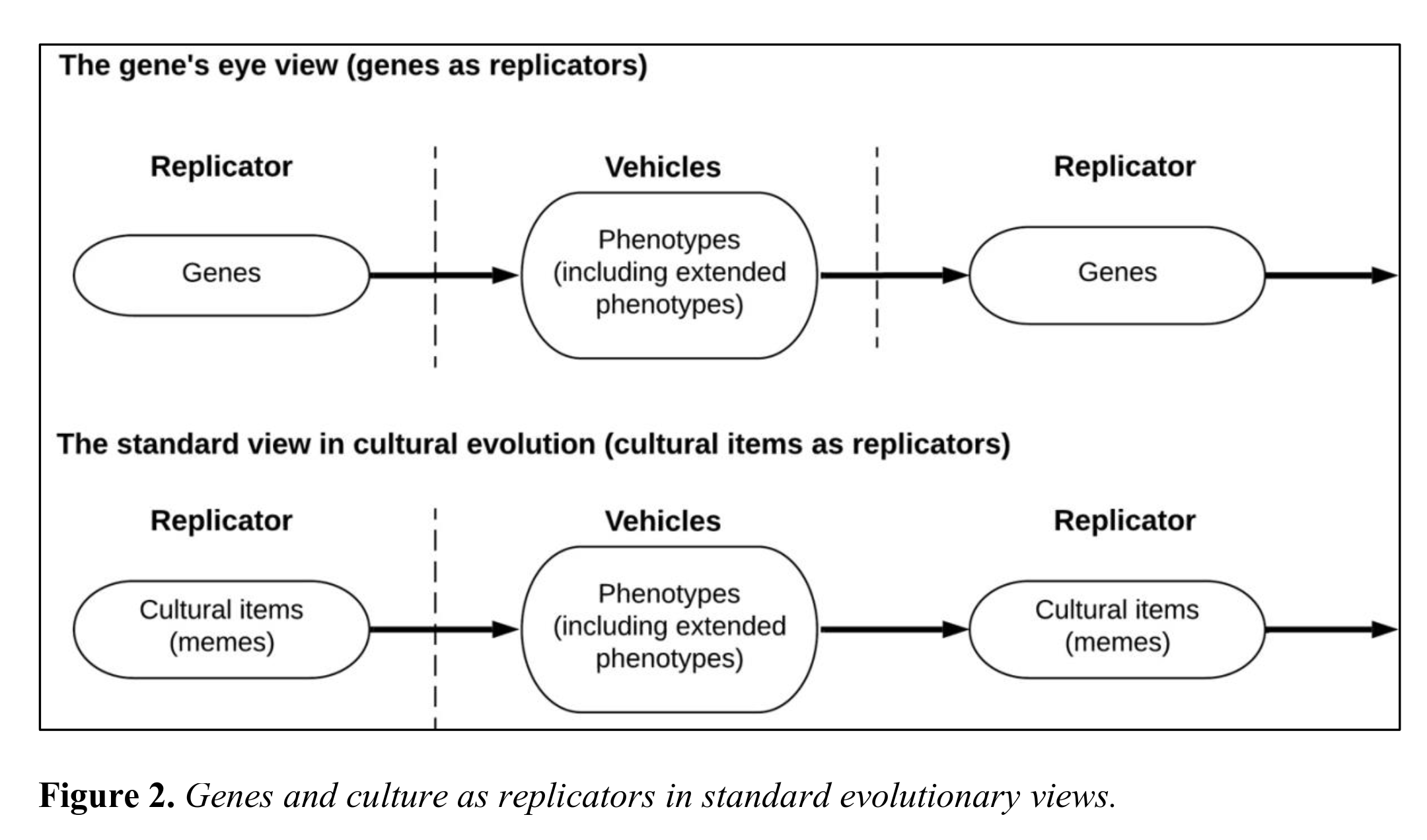

The paper argues that cultural products, such as ideas, tunes, fashions, or pots, are not replicators like genes or memes, but rather vehicles or extended phenotypes produced by the genes. The authors propose a gene’s-eye view of culture, in which cultural products are seen as adaptations to the environment that enhance the fitness of the genes that produce them. The authors contrast this view with the meme’s-eye view of culture, in which cultural products are seen as self-replicating entities that compete for transmission and survival. The authors claim that the gene’s-eye view of culture can better explain the diversity, complexity, and functionality of cultural products, as well as their coevolution with biological traits. The authors also discuss the implications of this view for understanding human cognition, cooperation, morality, and innovation. The paper provides several examples and models to illustrate the gene’s-eye view of culture and to compare it with the meme’s-eye view of culture. The paper concludes by suggesting some future directions for research on the gene-culture coevolution. [Bing AI summary]

Other animals than beavers alter their environment in accordance with their genes. The most extreme example, as is often the case, is humans. Humans build elaborate physical structures for living, storing materials and food. In contrast to beavers and other animals, human extended phenotypes build on each other to progress. That’s what gives rise to the “cultural evolution” or memetics (also originated by Dawkins a few years earlier), or whatever you prefer to call it. This process, however, ultimately depends on the genetics, so one might say that this process is itself a kind of complex extended phenotype.

There is a contrast between the two views of culture. Should we think of culture, memes, as a separate though intertwined parallel process? This view is the gene-culture co-evolution. There are many famous examples, such as the evolution of lactose (milk) tolerance in herding or pastoral cultures, leading to dramatic differences in dietary cultures that we still live with today.

Going back to the first perspective, animals aren’t really programmed to use the specific objects they find around them. They work like neural networks because they are neural networks. Just as our AIs will confuse similar-looking objects that no normal human would confuse, a beaver has no concept of wood in any scientific sense, but it will use whatever wood-like object to build dams. The same is seen for other species:

Crucially, bowerbirds and apes have been shown to be very innovative when they live in ecologies enriched by human activity (as well as by many other cognitively flexible species; Sol et al., 2008; Tuomainen & Candolin, 2011; Wright et al., 2010)). For instance, bowerbirds reuse plastic chips, coins, nails, rifle shells, or pieces of glass to build their bowers (Madden, 2008), and apes reuse cotton sheets, and shredded newspaper to build their nests (Anderson et al., 2021). Obviously, plastic chips and shredded newspapers are recent, and birds and apes did not evolve to use them. In Dawkins’ words, replicators associated with the use of plastic chips did not survive in the replicator pool at the expense of rival replicators. Should we say then, that bowers made of plastic chips and nests made of shredded newspapers are not “extended phenotypes” because they have emerged only recently? Obviously not. The proper function specified by evolution is not “to use leaves and pebbles to impress females”, but “to use any instrumentally relevant tool to attract females.” From this point of view, plastic chips, coins, nails, rifle shells, or pieces of glass are completely within the proper domain of the evolved motivation to build bowers, because what has led to the survival of genes of bower building is their ability to orchestrate in a flexible and innovative way the generative search for solutions to fulfill a higher-level goal: attracting the attention of females.

There are some ways that human extended phenotypes are different from non-human ones:

- Accumulative. Prior generations’ cultural artifacts and memes are reused for the next generation, leading to a separate process of cultural evolution, or memetics. It still depends on the genetic process, however. (There are a few cases of this in non-humans too, authors give the example of “Terrestrial hermit crabs architecturally remodel shells and pass these modified shelters to subsequent generations, which reuse them long after the original architect’s death”).

- Sharedness. Human extended phenotypes often don’t only reflect the genetics of one organism, but the joint effect of many. A beaver will build a dam, but usually alone. Human extended phenotypes are overwhelmingly a joint product of many organisms acting together, whether it is science, technology, fashion, or laws. (There are some non-human examples too, e.g. nests in monogamous birds are often a joint product.)

The authors end here, but one might be inclined to take it a lot further. If humans create elaborate extended phenotypes jointly, that means that we can also consider entire societies, countries and even broader civilizations as the extended phenotypes of the population’s joint genome. You can perhaps see where this is going. This implies that cultural differences are genetic in origin, that is, heritable between groups. To a biologist, this would not be too surprising, but social scientists usually refuse to take biology seriously. If we put these ideological glasses aside, we see that (East) Asians no matter where they go on Earth produce relatively similar cultures. The same is true for Europeans, Africans, Indians, and any other race you might think of. In this sense, then, we can talk of racial cultures. Wherever Scandinavians go, they create high trust, individualist societies. One can see the legacy of Scandinavian ancestry in many American areas, just as one can see the effects of German culture in many areas of Latin America, African culture in the Americas (whether they live on their own in the Caribbean or under the protection of other populations). This is despite these populations having given up their languages and explicit cultures many years ago, or literally being enslaved and forced to give it up. In other words, there is no escape from the genetic origins of the extended phenotype. The problem with the line of reasoning is that is is difficult to separate the genetic effects from the horizontal transmission between groups. Due to the invention of long distance communication and transport, something invented in Japan can now be found in Spain after a short duration. So in a sense, Spanish culture is also partially affected by Japanese genetics. The increasing mixing of humans both genetically (outbreeding) and by the internet means that national cultures are becoming more of a joint human culture, than a product of their own populations’ genome. The end result of this process will be panmixia both genetically and culturally. Since culture is more easily changed than genetics, this happens faster for culture. We see this already with the English language and Anglo-culture spreading everywhere on the globe.

Continuing this line of thought, it is possible to take it one step further. We can talk about human culture in general, as the joint product of collective mankind. This can be contrasted with other times in history when the genome was different, whether this was due to changes in the ancestral composition (e.g. relatively fewer Europeans), or due to selection (e.g. increasing intelligence since our split from the apes, or the recent decline in genetic intelligence from dysgenics). Thus, this perspective also coheres with the use of ancient genomes to study history, as has become possible in the last few years. See my prior post on the most comprehensive of these studies, and I can also say that Davide Piffer and I are in the final process of a big update on this front.

There is one final step further we can take this. We can think of the entire biome of the Earth as the joint phenotype of our collective genomes, from viruses, bacteria, to plants, birds, and mammals. If any non-Earth life is ever discovered before we kill ourselves off, we could contrast life as it works on Earth with life as it works on their planet. The differences will, of course, be due to genetics, in the abstract sense of whatever their hereditary units of selection are. Food for thought.