Back in 2018, I wrote about classroom separation studies. It’s one clever way to use the already existing twin data to examine specific environmental causes. Many people will claim that teachers or peers or other classroom-related factors like pupils per teacher are important. If these are important, we expect that twins who are in the same classroom or go to the same school are more similar than those who don’t. It turns out they are no different. This result isn’t based on small samples and lack of precision, but on the combined data of 13,000+ twins from 6 countries. They looked at not just school performance, but also various non-cognitive or personality traits like desire to learn. It doesn’t appear there is much to hope for. This brings us to a new study done using the awesome Danish register data:

- Hassan, S., Hvidtfeldt, C., Andersen, L. H., & Udsen, R. O. (2023). Do refugee children impair the academic performance of native children in the school? Informative null results from Danish Register Data. European Sociological Review, 39(3), 352-365.

Discussions concerning the social impact of accepting refugee immigrants arise each time large numbers of refugees apply for protection in rich countries. However, little evidence exists on how the integration of refugees into core welfare institutions affects native citizens who depend on and interact with these institutions. In this paper, we focus on whether receiving refugees in a school cohort affects the academic performance of natives, using administrative data from Denmark, which contain test scores on all children in public schools. We exploit variation in the timing of refugees’ entrance to schools to facilitate causal estimates. Our findings show that refugees tend to cluster in schools that had poorer performance even prior to the refugees’ arrival. When we take this selection pattern into account, the effect of receiving refugees on the academic performance trajectory of natives is both statistically insignificant and substantially unimportant.

When migrants come in, they end up in certain schools and their peers (classmates) tend to have below average performance. Is that caused by the new arrivals, or were their performance below average to begin with? It turns out it is selection. Granted, the unadjusted effect sizes were tiny to begin with, so it wasn’t of much relevance to begin with:

Focussing on the binary treatment variable, our results suggest that refugee children, on average, enter school cohorts that score 6.7 per cent (7.8 per cent) of a standard deviation lower in Danish (mathematics) in the unconditional model. Controlling for observed background characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, and parental socio-economic status, reduces this estimate to 1 per cent (1.8 per cent) of a standard deviation, which is both small and statistically insignificant. This result suggests that over and above the background characteristics included in our model, there is only little to no additional selection of refugee children into schools. Adding school fixed effects further reduces this estimate to 0.4 per cent (0.1 per cent) of a standard deviation.

Yes, they are talking about Cohen’s d of 0.07 and 0.08 before controls (that is, about 1.2 IQ), and 0.01 and 0.02 after controls, and below 0.01 after adjusting for non-random placement.

The authors note that the results are consistent with 2 other Nordic studies from Sweden and Norway:

Our findings are in line with the results from a similar study from Sweden (Brandén et al., 2018), but reach slightly different results compared to a Norwegian study which finds small negative effects on mathematics, but no effects on reading (Green and Iversen, 2022). One key difference between our study and the Norwegian study is that we do not count children of refugees who were either born in or lived in Denmark for more than 3 years as ‘refugee children’; a detail that we are able to incorporate because of the unmatched detail of the Danish Immigration Register. Finally, we have argued that refugee children are likely to exert stronger externalities on native students, compared with other immigrant children. Focussing on refugee peer effects, therefore, has the strategic advantage of being ‘a most likely case study’, and our findings, therefore, have implications beyond our narrow focus on refugees.

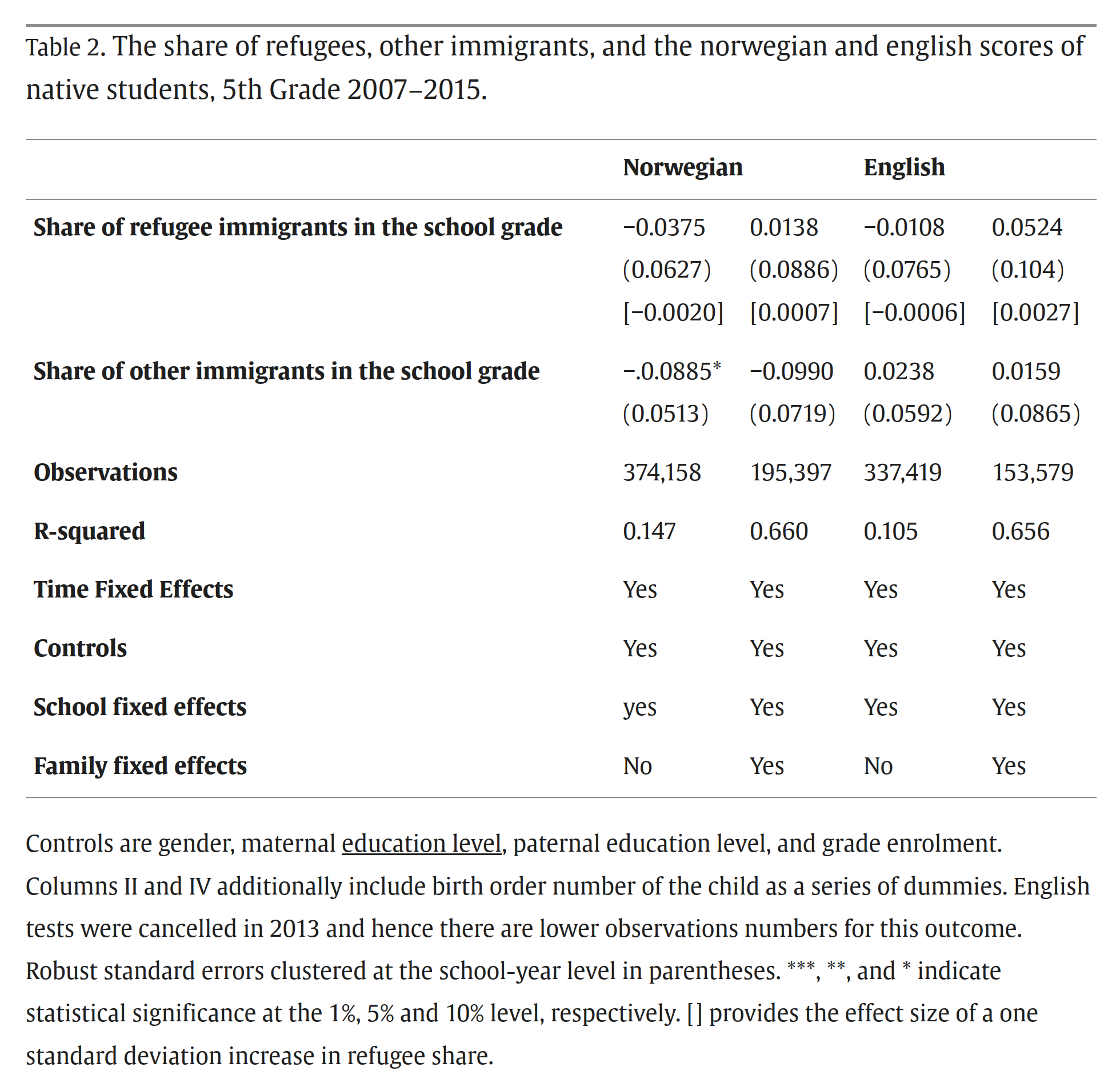

Oh and that Norwegian result for mathematics? It’s truly an economist study in the worst way:

You read that right, a single p < .10 finding based on a sample size of…. 374,000! How does this stuff continue to get published? Who knows.

These 3 peer effect studies taken together with the twin classroom separation studies discussed above clearly show that it doesn’t matter very much who your classmates are insofar as your own performance is concerned. It just matters who you are.