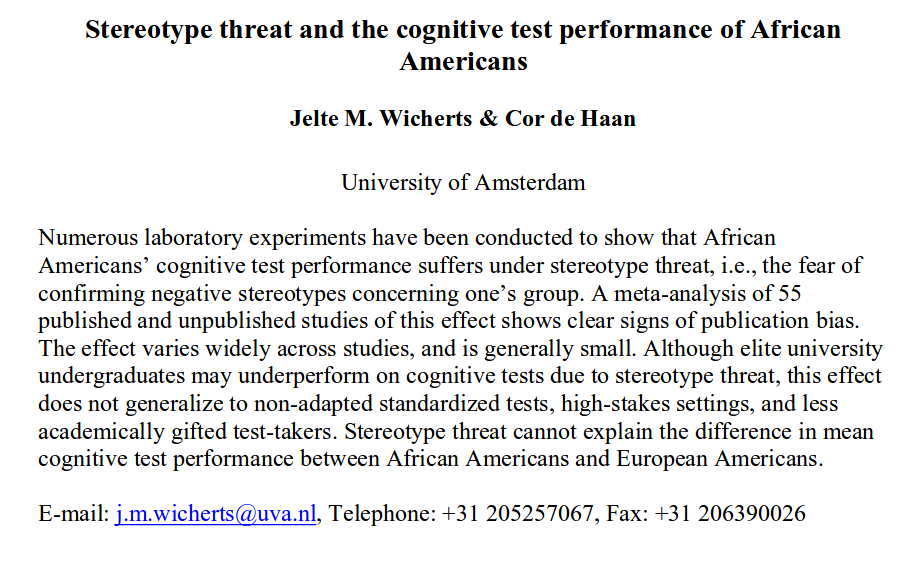

In the program for the 2009 ISIR conference, we find something interesting:

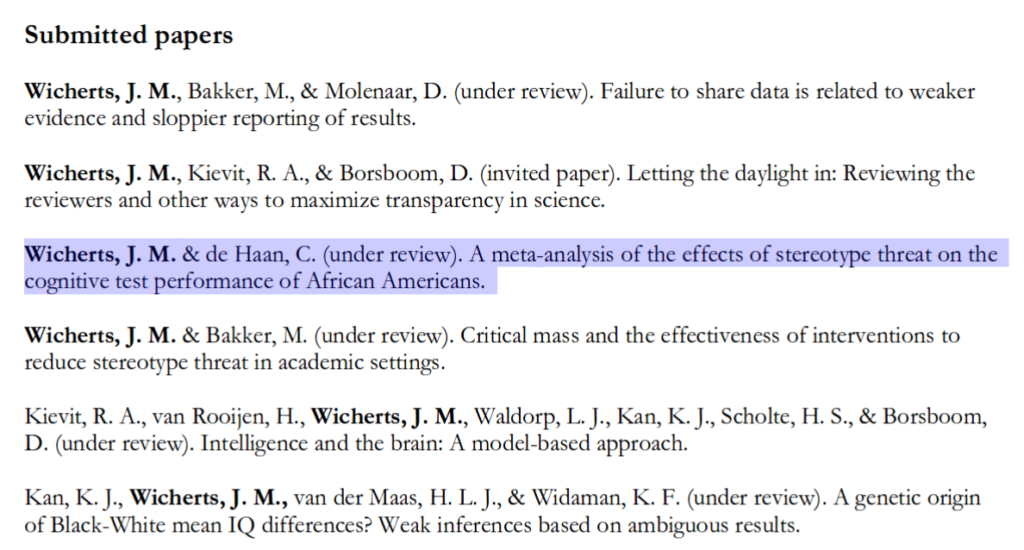

In Jelte’s CV from 2011, we see it too:

It’s also there in the 2012 version, but it has disappeared in the 2014 version. Occasionally, one can find references to it in other places:

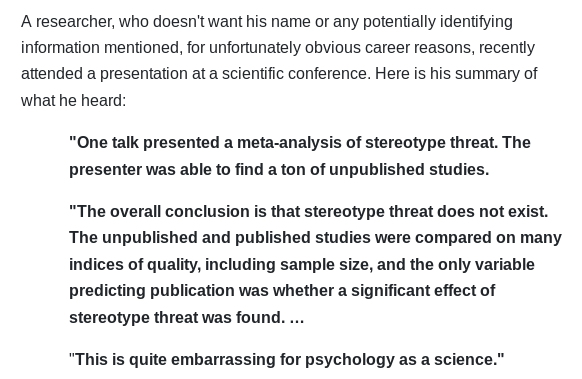

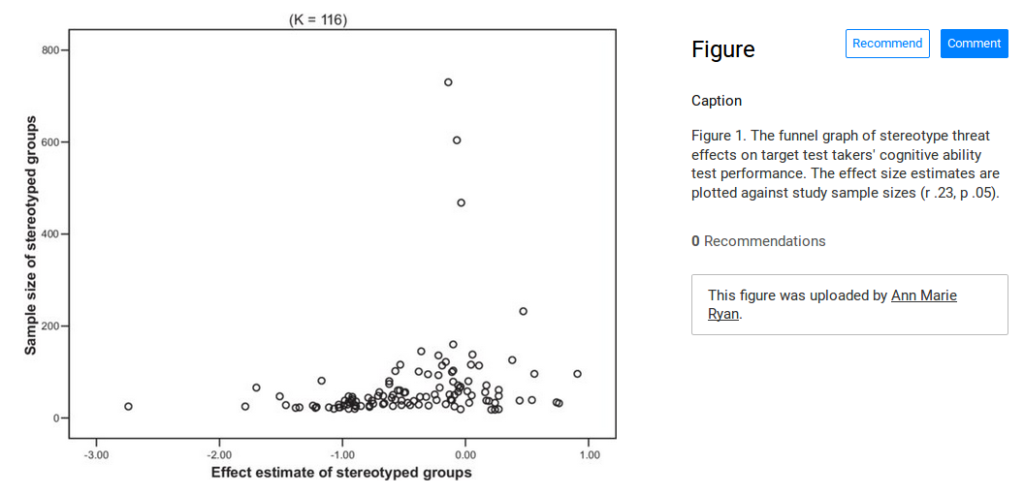

So, one might guess that it was censored “lost in review”. We can guess at this because a previous meta-analysis of stereotype threat for “minorities” (women are not a minority!) produced a scatterplot like this:

And Wichert’s later student Paulette Flore produced a great dissertation (read it!) for stereotype threat on women, finding:

Do gender stereotypes lead to performance decrement on math tests for girls or women? Psychologists across the world have tried to answer this question using experiments for the last two decades. In these experiments a group of students is exposed to stereotype threat before making a math test. Stereotype threat can be made salient in different ways, for instance by informing participants that “boys and girls do not perform equally well on this math test”. In a control condition a second group of students do not get to read this, or they are informed that “boys and girls perform equally well on this math test”. Female students often underperform on a math test when they are exposed to stereotype threat, while male students are not influenced.

In my dissertation we study stereotype threat literature and popular research methods with a critical eye. We need to be critical, because some problems in the psychological literature could have distorted research findings in the past, like publication bias (results are biased by selectively publishing studies with exciting results), and a lack of replicability (being able to replicate the findings of the original study by means of a new study) and reproducibility (coming to the same conclusions as the original researchers by reanalyzing the existing dataset). Moreover, stereotype threat researchers mostly study whether performance decrements on the math test occur on average scores. In my dissertation I go beyond averages, and study group differences caused by stereotype threat for specific math questions. With statistical models we study whether girls influenced by stereotype threat score lower on specific math questions than girls in the control condition (controlled for math ability), we call this Differential Item Functioning (DIF).

In Chapter 2 of my dissertation we summarize existing stereotype threat studies conducted in elementary, middle and high schools across the globe by means of a meta-analysis. We found a negative influence of stereotype threat on math performance, even though the differences between the groups were small. Tests for publication bias implied that the results are somewhat distorted due to selective publishing. In Chapter 3 we carried out a large stereotype threat replication study in Dutch high schools. More than 2,000 students participated in this study. We did not find evidence for a stereotype threat effect on math performance in this study. In Chapter 4 we study used DIF methods and reporting practices in 200 articles. We conclude that the amount of detail in reports on DIF analyses is often insufficient, which is problematic for reproducibility. It is striking that researchers who study DIF with multiple statistical methods, often find divergent results. Finally, in Chapter 5 we reanalyze data of 10 stereotype threat experiments. We found no systematic differences in stereotype threat effects for difficult or easy questions. The amount of unanswered math questions was high in some of the studies, which reflects the strong time pressure students had to work under. We suggest as alternative explanation for performance decrements that female students in the stereotype threat condition work slower or give up more easily than female students in the control condition. A DIF analysis on our own dataset does not show any differences in performance on specific items for the female students in the different experimental groups. We recommend researchers and policy makers to be critical when interpreting outcomes in stereotype threat and DIF literature. In the future, large scale systematic replication studies could answer many of the pending questions regarding the stereotype threat effect.

She is too modest. They did a big meta-analysis for the female math stereotype threat and found the publication patterns very suspicious. Then they did a big pre-registered replication and found no evidence for it at all. The right conclusion here is that it isn’t real, and never was. If people did proper experiments to begin with, the literature wouldn’t be full of these non-existent phenomena. (See also the brand new Many Labs 2 project paper which found that 50% of 28 studies could be replicated, many of which were considered classics.) Someone even cited it in a publisher paper:

And yes, I have asked Jelte to post the preprint at least 5 times.