-

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity (Vol. 12). Cambridge University Press.

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity (Vol. 12). Cambridge University Press.-

The book is on LibGen

-

I continue my Eysenck readings with his popular genius book (prior review The Psychology of Politics (1954)). Having previously read some of Simonton’s work, Eysenck sure is a very different beast! The writing style follows the usual style: candid, emphasizing of uncertainty when present, funny, and very wide ranging. In fact, regarding replication, Eysenck is almost modern, always asking for replications of experiments, and saying that it is a waste of time to do studies with n < 100!

I don’t have time to write a big review, but I have marked a bunch of interesting passages, and I will quote them here. Before doing so, however, the reader should know that there is now a memorial site for Hans Eysenck too, with free copies of his work. It’s not complete yet, his bibliography is massive! https://hanseysenck.com/ I host it, but it’s created by a 3rd person.

Let’s begin. Actually, I forgot to note interesting passages in the first half of the book, so these are all from second part. Eysenck discusses the role of the environment in origins of genius, and illustrates with an unlikely case:

Our hero was born during the American Civil War, son of Mary, a Negro slave on a Missouri farm owned by Moses Carver and his wife Susan. Mary, who was a widow, had two other children – Melissa, a young girl, and a boy, Jim; George was the baby. In 1862 masked bandits who terrorized the countryside and stole livestock and slaves attacked Carver’s farm, tortured him and tried to make him tell where his slaves were hidden; he refused to tell. After a few weeks they came back, and this time Mary did not have time to hide in a cave, as she had done the first time; the raiders dragged her, Melissa and George away into the bitter cold winter’s night. Moses Carver had them followed, but only George was brought back; the raiders had given him away to some womenfolk saying ‘he ain’t worth nutting’. Carver’s wife Susan nursed him through every conceivable childhood disease that his small frame seemed to be particularly prone to; but his traumatic experiences had brought on a severe stammer which she couldn’t cure. He was called Carver’s George; his true name (if such a concept had any meaning for a slave) is not known. When the war ended the slaves were freed, but George and Jim stayed with the Carvers. Jim was sturdy enough to become a shepherd and to do other farm chores; George was a weakling and helped around the house. His favourite recreation was to steal off to the woods and watch insects, study flowers, and become acquainted with nature. He had no schooling of any kind, but he learned to tend flowers and became an expert gardener. He was quite old when he saw his first picture, in a neighbour’s house; he went home enchanted, made some paint by squeezing out the dark juices of some berries, and started drawing on a rock. He kept on experimenting with drawings, using sharp stones to scratch lines on the smooth pieces of earth. He became known as the ‘plant doctor’ in the neighbourhood, although still only young, and helped everyone with their gardens.

At some distance from the farm there was a one-room cabin that was used as a school house during the week; it doubled as a church on Sundays. When George discovered its existence, he asked Moses Carver for permission to go there, but was told that no Negroes were allowed to go to that school. George overcame his shock at this news after a while; Susan Carver discovered an old spelling-book, and with her help he soon learned to read and write. Then he discovered that at Neosho, eight miles away, there was a school that would admit Negro children. Small, thin and still with his dreadful stammer, he set out for Neosho, determined to earn some money to support himself there. Just 14 years old, he made his home with a coloured midwife and washerwoman. ‘That boy told me he came to Neosho to find out what made hail and snow, and whether a person could change the colour of a flower by changing the seed. I told him he’d never find that out in Neosho. Maybe not even in Kansas City. But all the time I knew he’d find it out – somewhere.’ Thus Maria, the washerwoman; she also told him to call himself George Carver – he just couldn’t go on calling himself Carver’s George! By that name, he entered the tumbledown shack that was the Lincoln School for Coloured Children, with a young Negro teacher as its only staff member. The story of his fight for education against a hostile environment is too long to be told here; largely self-educated he finally obtained his Bachelor of Science degree at the age of 32, specialized in mycology (the study of fungus growths) became an authority in his subject, and finally accepted an invitation from Booker T. Washington, the foremost Negro leader of his day, to help him fund a Negro university. He accepted, and his heroic struggles to create an institute out of literally nothing are part of Negro history. He changed the agricultural and the eating habits of the South; he created single-handed a pattern of growing food, harvesting and cooking it which was to lift Negroes (and whites too!) out of the abject state of poverty and hunger to which they had been condemned by their own ignorance. And in addition to all his practical and teaching work, administration and speech-making, he had time to do creative and indeed fundamental research; he was one of the first scientists to work in the field of synthetics, and is credited with creating the science of chemurgy – ‘agricultural chemistry’. The American peanut industry is based on his work; today this is America’s sixth most important agricultural product, with many hundreds of by-products. He became more and more obsessed with the vision that out of agriculture and industrial waste useful material could be created, and this entirely original idea is widely believed to have been Carver’s most important contribution. The number of his discoveries and inventions is legion; in his field, he was as productive as Edison. He could have become a millionaire-many times over but he never accepted money for his discoveries. Nor would he accept an increase in his salary, which remained at the 125 dollars a month (£100 per year) which Washington had originally offered him. (He once declined an offer by Edison to work with him at a minimum annual salary of 100000 dollars.) He finally died, over 80, in 1943. His death was mourned all over the United States. The New York Herald Tribune wrote: ‘Dr, Carver was, as everyone knows, a Negro. But he triumphed over every obstacle. Perhaps there is no one in this century whose example has done more to promote a better understanding between the races. Such greatness partakes of the eternal.’ He himself was never bitter, in spite of all the persecutions he and his fellow-Negroes had to endure. ‘No man can drag me down so low as to make me hate him.’ This was the epitaph on his grave. He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honour in being helpful to the world.

On Simonton‘s model of creativity:

Simonton’s own theory is interesting but lacks any conceivable psychological support. He calls his theory a ‘two-step’ model; he postulates that each individual creator begins with a certain ‘creative potential’ defined by the total number of contributions the creator would be capable of producing in an unrestricted life span. (Rather like a woman’s supply of ova!) There are presumably individual differences in this initial creative potential, which Simonton hardly mentions in the development of his theory. Now each creator is supposed to use up his supply of creative potential by transforming potential into actual contributions. (There is an obvious parallel here with potential energy in physics.) This translation of creative potential into actual creative products implies two steps. The first involves the conversion of creative potential into creative ideation, in the second step these ideas are worked into actual creative contributions in a form that can be appreciated publicly (elaboration). It is further assumed that the rate at which ideas are produced is proportional to the creative potential at a given time, and that the rate of elaboration if ‘proportional to the number of ideas in the works’ (Simonton, 1984b; p. 110). Simonton turns these ideas into a formula which generates a curve which gives a correlation between predicted and observed values in the upper 90s (Simonton, 1983b). The theory is inviting, but essentially untestable – how would we measure the ‘creative potential’ which presumably is entirely innate, and should exist from birth? How could we measure ideation, or elaboration, independently of external events? Of course the curve fits observations beautifully, but then all the constants are chosen to make sure of such a fit! Given the general shape of the curve (inverted U), many formulae could be produced to give such a fit. Unless we are shown ways of independently measuring the variables involved, no proper test of any underlying psychological theory exists.

On geniuses misbehavior, featuring Newton:

Less often remarked, but possibly even more insidious, is the resistance by scientists to ‘scientific discovery’, as Barker (1961) has named this phenomenon. As he point out, in two systematic analyses of the social process of scientific discovery and invention, analyses which tried to be as inclusive of empirical facts and theoretical problems as possible, there was only one passing reference to such resistance in the one instance and none at all in the second (GilfiUan, 1935; Barker, 1952). This contrasts markedly with the attention paid to the resistance to scientific discovery on the part of economic, technological, religious ideological elements and groups outside science itself (Frank, 1957; Rossman, 1931; Shyrock, 1936; Stamp, 1937). This neglect is probably based on the erroneous notion embodied in the title of Oppenheimer‘s (1955) book The Open Mind; we assume all too readily that objectivity is the characteristic of the scientist, and that he will impartially consider all the available facts and theories. Polanyi (1958, 1966) has emphasized the importance of the personality of the scientist, and no one familiar with the history of science can doubt that individual scientists are as emotional, jealous, quirky, self-centred, excitable, temperamental, ardent, enthusiastic, fervent, impassioned, zealous and hostile to competition as anyone else. The incredibly bellicose, malevolent and rancorous behaviour of scientists engaged in disputes about priority illustrates the truth of this statement. The treatment handed out to Halton Arp (1987), who dared to doubt the cosmological postulate about the meaning and interpretation of the red-shift is well worth pondering (Flanders, 1993). Objectivity flies out of the window when self-interest enters (Hagstrom, 1974).

The most famous example of a priority dispute is that between Newton and Leibnitz, concerning the invention of the calculus (Manuel, 1968). The two protagonists did not engage in the debate personally, but used proxies, hangers-on who would use their vituperative talents to the utmost in the service of their masters. Newton in particular abused his powers as President of the Royal Society in a completely unethical manner. He nominated his friends and supporters to a theoretically neutral commission of the Royal Society to consider the dispute; he wrote the report himself, carefully keeping his own name out of it, and he personally persecuted Leibnitz beyond the grave, insisting that he had plagiarized Newton’s discovery – which clearly was untrue, as posterity has found. Neither scientist emerges with any credit from the Machiavellian controversy, marred by constant untruths, innuendos of a personal nature, insults, and outrageous abuse which completely obscured the facts of the case. Newton behaved similarly towards Robert Hooke, Locke, Flamsted and many others; as Manuel (1968) says. ‘Newton was aware of the mighty anger that smouldered within him all his life, eternally seeking objects. … many were the times when (his censor) was overwhelmed and the rage could not be contained’ (p. 343). ‘Even if allowances are made for the general truculence of scientists and learned men, he remains one of the most ferocious practitioners of the art of scientific controversy. Genteel concepts of fair play are conspicuously absent, and he never gave any quarter’ (p. 345). So much for scientific objectivity!

More Newton!:

Once a theory has been widely accepted, it is difficult to displace, even though the evidence against it may be overwhelming. Kuhn (1957) points out that even after the publication of De Revolutionibus most astronomers retained their belief in the central position of the earth; even Brahe (Thoren, 1990) whose observations were accurate enough to enable Kepler (Caspar, 1959) to determine that the Mars orbit around the sun was elliptical, not circular, could not bring himself to accept the heliocentric view. Thomas Young proposed a wave theory of light on the basis of good experimental evidence, but because of the prestige of Newton, who of course favoured a corpuscular view, no-one accepted Young’s theory (Gillespie, 1960). Indeed, Young was afraid to publish the theory under his own name, in case his medical practice might suffer from his opposition to the god-like Newton! Similarly, William Harvey’s theory of the circulation of the blood was poorly received, in spite of his prestigious position as the King’s physician, and harmed his career (Keele, 1965). Pasteur too was hounded because his discovery of the biological character of the fermentation process was found unacceptable. Liebig and many others defended the chemical theory of these processes long after the evidence in favour of Pasteur was conclusive (Dubos, 1950). Equally his micro-organism theory of disease caused endless strife and criticism. Lister’s theory of antisepsis (Fisher, 1977) was also long argued over, and considered absurd; so were the contributions of Koch (Brock, 1988) and Erlich (Marquardt, 1949). Priestley (Gibbs, 1965) retained his views of phlogiston as the active principle in burning, and together with many others opposed the modern theories of Lavoisier, with considerable violence. Alexander Maconochie’s very successful elaboration and application of what would now be called ‘Skinnerian principle’ to the reclamation of convicted criminals in Australia, led to his dismissal (Barry, 1958).

But today is different! Or maybe not:

The story is characteristic in many ways, but it would be quite wrong to imagine that this is the sort of thing that happened in ancient, far-off days, and that nowadays scientists behave in a different manner. Nothing has changed, and I have elsewhere described the fates of modern Lochinvars who fought against orthodoxy and were made to suffer mercilessly (Eysenck, 1990a). The battle against orthodoxy is endless, and there is no chivalry; if power corrupts (as it surely does!), the absolute power of the orthodoxy in science corrupts absolutely (well, almost!). It is odd that books on genius seldom if ever mention this terrible battle that originality so often has when confronting orthodoxy. This fact certainly accounts for some of the personality traits so often found in genius, or even the unusually creative non-genius. The mute, inglorious Milton is a contradiction in terms, an oxymoron; your typical genius is a fighter, and the term ‘genius’ is by definition accorded the creative spirit who ultimately (often long after his death) wins through. An unrecognized genius is meaningless; success socially defined is a necessary ingredient. Recognition may of course be long delayed; the contribution of Green (Connell, 1993) is a good example.

On fraud in science, after discussing Newton’s fudging of data, and summarizing Kepler‘s:

It is certainly startling to find an absence of essential computational details because ‘taediesum esset’ to give them. But worse is to follow. Donahue makes it clear that Kepler presented theoretical deduction as computations based upon observation. He appears to have argued that induction does not suffice to generate true theories, and to have substituted for actual observations figures deduced from the theory. This is historically interesting in throwing much light on the origins of scientific theories, but is certainly not a procedure recommended to experimental psychologists by their teachers!

Many people have difficulties in understanding how a scientist can fraudulently ‘fudge’ his data in this fashion. The line of descent seems fairly clear. Scientists have extremely high motivation to succeed in discovering the truth; their finest and most original discoveries are rejected by the vulgar mediocrities filling the ranks of orthodoxy. They are convinced that they have found the right answer; Newton believed it had been vouchsaved him by God, who explicitly wanted him to preach the gospel of divine truth. The figures don’t quite fit, so why not fudge them a little bit to confound the infidels and unbelievers? Usually the genius is right, of course, and we may in retrospect excuse his childish games, but clearly this cannot be regarded as a licence for non-geniuses to foist their absurd beliefs on us. Freud is a good example of someone who improved his clinical findings with little regard for facts (Eysenck, 1990b), as many historians have demonstrated. Quod licet Jovi non licet bovi – what is permitted to Jupiter is not allowed the cow!

One further point. Scientists, as we shall see, tend to be introverted, and introverts show a particular pattern of level of aspiration (Eysenck, 1947) – it tends to be high and rigid. That means a strong reluctance to give up, to relinquish a theory, to acknowledge defeat. That, of course, is precisely the pattern shown by so many geniuses, fighting against external foes and internal problems. If they are right, they are persistent; if wrong, obstinate. As usual the final result sanctifies the whole operation (fudging included); it is the winners who write the history books!

The historical examples would seem to establish the importance of motivational and volitional factors, leading to persistence in opposition against a hostile world, and sometimes even to fraud when all else fails. Those whom the establishment refuses to recognize appropriately fight back as best they can; they should not be judged entirely by the standards of the mediocre!

This example and the notes about double standards for genius is all the more interesting in the recent light of problems with Eysenck’s own studies, published with yet another maverick!

And now, to sunspots and genius:

Ertel used recorded sun-spot activity going back to 1600 or so, and before that by analysis of the radiocarbon isotope CI4, whose productions as recorded in trees, which give an accurate picture of sun-spot activity. Plotted in relation to sun-spot activity were historical events, either wars, revolutions, etc. or specific achievements in painting, drama, poetry, science and philosophy. Note that Ertel’s investigations resemble a ‘double blind’ paradigm, in that the people who determined the solar cycle, and those who judged the merits of the artists and scientists in question, were ignorant of the purpose to which Ertel would put their data, and did not know anything about the theories involved. Hence the procedure is completely objective, and owes nothing to Ertel’s views, which in any case were highly critical of Chizhevsky’s ideas at the beginning.

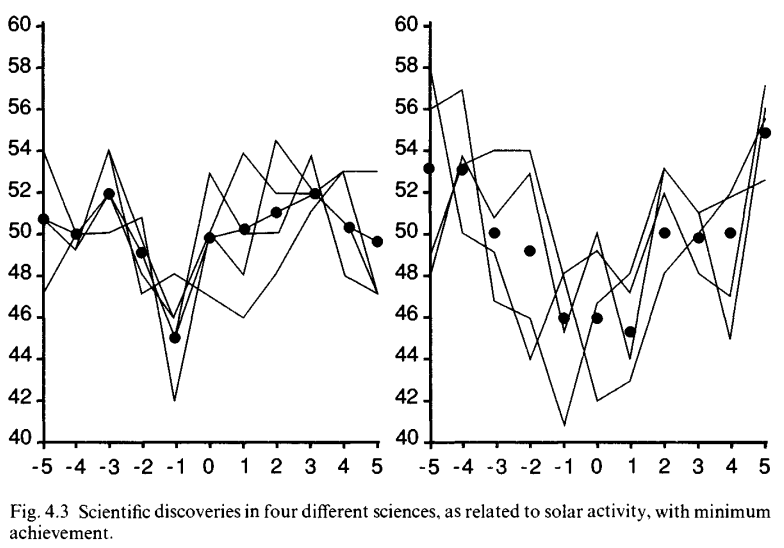

The irregularities of the solar cycle present difficulties to the investigator, but also, as we shall see, great advantages. One way around this problem was suggested by Ertel; it consists of looking at each cycle separately; maximum solar activity (sol. max.) is denoted 0, and the years preceding or succeeding 0 are marked -1, -2, -3 etc., or +1, +2, +3 etc. Fig. 4.2 shows the occurrence of 17 conflicts between socialist states from 1945 to 1982, taken from a table published by the historian Bebeler, i.e. chosen in ignorance of the theory. In the figure the solid circles denote the actual distribution of events, the empty circles the expected distribution on a chance basis. Agreement with theory is obvious, 13 of the 17 events occurring between – 1 and + 1 solar maximum (Ertel, 1992a,b).

Actually Ertel bases himself on a much broader historical perspective, having amassed 1756 revolutionary events from all around the world, collected from 22 historical compendia covering the times from 1700 to the present. There appears good evidence in favour of Chizhevsky’s original hypothesis. However, in this book we are more concerned with Ertel’s extension to cultural events, i.e. the view that art and science prosper most when solar activity is at a minimum. Following his procedure regarding revolutionary events, Ertel built up a data bank concerned with scientific discoveries. Fig. 4.3 shows the outcome; the solid lines show the relation between four scientific disciplines and solar activity, while the black dots represent the means of the four scientific disciplines. However, as Ertel argues, the solar cycle may be shorter or longer than 11 years, and this possibility can be corrected by suitable statistical manipulation; the results of such manipulation, which essentially records strength of solar activity regardless of total duration of cycle, are shown on the right. It will be clear that with or without correction for duration of the solar cycle, there is a very marked U-shaped correlation with this activity, with an average minimum of scientific productivity at points -1,0 and -I-1, as demanded by the theory.

Intriguing! Someone must have tested this stuff since. It should be easy to curate a large dataset from Murray’s Human Accomplishment or Wikipedia based datasets, and see if it holds up. More generally, it is somewhat in line with quantitative historical takes by clio-dynamics people.

Intuition vs. thinking, system 1 vs. 2, and many other names:

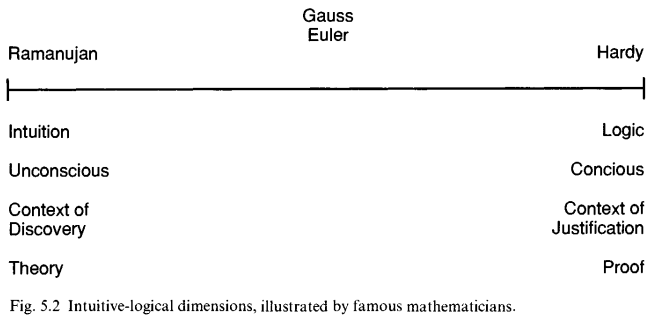

It was of course Jung (1926) who made intuition one of the four functions of his typology (in addition to thinking, feeling, and sensation). This directed attention from the process of intuition to intuition as a personality variable – we can talk about the intuitive type as opposed to the thinking type, the irrational as opposed to the rational. (Feeling, too, is rational, while sensation is irrational, i.e. does not involve a judgment.) Beyond this, Jung drifts of Tinto the clouds peopled with archetypes and constituted of the ‘collective unconscious’, intuitions of which are held to be far more important than intuitions of the personal unconscious. Jung’s theory is strictly untestable, but has been quite important historically in drawing attention to the intuitive person’, or intuition as a personality trait.

Jung, like most philosophers, writers and psychologists, uses the contrast between ‘intuition’ and logic’ as an absolute, a dichotomy of either – or. Yet when we consider the definitions and uses of the terms, we find that we are properly dealing with a continuum, with ‘intuition’ and logic’ at opposite extremes, rather like the illustration in Fig. 5.2. In any problem-solving some varying degree of intuition is involved, and that may be large or small in amount. Similarly, as even Jung recognized, people are more or less intuitive; personalities are ranged along a continuum. It is often easier to talk as if we were dealing with dichotomies (tall vs. short; bright vs. dumb; intuitive vs. logical), but it is important to remember that this is not strictly correct; we always deal with continua.

The main problem with the usual treatment of ‘intuition’ is the impossibility of proof; whatever is said or postulated is itself merely intuitive, and hence in need of translation into testable hypotheses. Philosophical or even common- sense notions of intuition, sometimes based on experience as in the case of Poincare, may seem acceptable, but they suffer the fate of all introspection – they may present us with a problem, but do not offer a solution.

The intuitive genius of Ramanujan:

For Hardy, as Kanigel says, Ramanujan’s pages of theorems were like an alien forest whose trees were familiar enough to call trees, yet so strange they seemed to come from another planet. Indeed, it was the strangeness of Ramanujan’s theorems, not their brilliance, that struck Hardy first. Surely this was yet another crank, he thought, and put the letter aside. However, what he had read gnawed at his imagination all day, and finally he decided to take the letter to Littlewood, a mathematical prodigy and friend of his. The whole story is brilliantly (and touchingly) told by Kanigel; fraud or genius, they asked themselves, and decided that genius was the only possible answer. All honour to Hardy and Littlewood for recognizing genius, even under the colourful disguise of this exotic Indian plant; other Cambridge mathematicians, like Baker and Hobson, had failed to respond to similar letters. Indeed, as Kanigel says, ‘it is not just that he discerned genius in Ramanujan that stands to his credit today; it is that he battered down his own wall of skepticism to do so’ (p. 171).

The rest of his short life (he died at 33) Ramanujan was to spend in Cambridge, working together with Hardy who tried to educate him in more rigorous ways and spent much time in attempting to prove (or disprove!) his theorems, and generally see to it that his genius was tethered to the advance- ment of modern mathematics. Ramanujan’s tragic early death left a truly enormous amount of mathematical knowledge in the form of unproven theorems of the highest value, which were to provide many outstanding mathematicians with enough material for a life’s work to prove, integrate with what was already known, and generally give it form and shape acceptable to orthodoxy. Ramanujan’s standing may be illustrated by an informal scale of natural mathematical ability constructed by Hardy, on which he gave himself a 25 and Littlewood a 30. To David Hilbert, the most eminent mathematician of his day, he gave an 80. To Ramanujan he gave 100! Yet, as Hardy said:

the limitations of his knowledge were as startling as its profundity. Here was man who could work out modular equations and theorems of complex multiplication, to orders unheard of, whose mastery of continued fractions was, on the formal side at any rate, beyond that of any mathematician in the world, who had found for himself the functional equation of the Zeta- function, and the dominant terms of many of the most famous problems in the analytical theory of numbers; and he had never heard of a doubly periodic function or of Cauchy’s theorem, and had indeed but the vaguest idea of what a function of a complex variable was. His ideas as to what constituted a mathematical proof were of the most shadowy description. All his results, new or old, right or wrong, had been arrived at by a process of mingled arguments, intuition, and induction, of which he was entirely unable to give any coherent account (p. 714).

Ramanujan’s life throws some light on the old question of the ‘village Hampden’ and ‘mute inglorious Milton’; does genius always win through, or may the potential genius languish unrecognized and undiscovered? In one sense the argument entails a tautology: if genius is defined in terms of social recognition, an unrecognized genius is of course a contradicto in adjecto. But if we mean, can a man who is a potential genius be prevented from demonstrating his abilities?, then the answer must surely be in the affirmative. Ramanujan was saved from such a fate by a million-to-one accident. All his endeavours to have his genius recognized in India had come to nothing; his attempts to interest Baker and Hobson in Cambridge came to nothing; his efforts to appeal to Hardy almost came to nothing. He was saved by a most unlikely accident. Had Hardy not reconsidered his first decision, and consulted Littlewood, it is unlikely that we would ever have heard of Ramanujan! How many mute inglorious Miltons (and Newtons, Einsteins and Mendels) there may be we can never know, but we may perhaps try and arrange things in such a way that their recognition is less likely to be obstructed by bureaucracy, academic bumbledom and professional envy. In my experience, the most creative of my students and colleagues have had the most difficulty in finding recognition, acceptance, and research opportunities; they do not fit in, their very desire to devote their lives to research is regarded with suspicion, and their achievements inspire envy and hatred.

Eysenck talks about his psychoticism construct, which is almost the same as the modern general psychopathology factor, both abbreviated to P:

The study was designed to test Kretschmer’s (1946, 1948) theory of a schizothymia-cyclothymia continuum, as well as my own theory of a norma- lity-psychosis continuum. Kretschmer was one of the earliest proponents of a continuum theory linking psychotic and normal behaviour. There is, he argued, a continuum from schizophrenia through schizoid behaviour to normal dystonic (introverted) behaviour; on the other side of the continuum we have syntonic (extraverted) behaviour, cycloid and finally manic-depres- sive disorder. He is eloquent in discussing how psychotic abnormality shades over into odd and eccentric behaviour and finally into quite normal typology. Yet, as I have pointed out (Eysenck, 1970a,b), the scheme is clearly incom- plete. We cannot have a single dimension with ‘psychosis’ at both ends; we require at least a two dimensional scheme, with psychosis-normal as one axis, and schizophrenia-affective disorder as the other.

In order to test this hypothesis, I designed a method of ‘criterion analysis’ (Eysenck, 1950, 1952a,b), which explicitly tests the validity of continuum vs. categorical theories. Put briefly, we take two groups (e.g. normal vs. psycho- tic), and apply to both objective tests which significantly discriminate between the groups. We then intercorrelate the tests within each group, and factor analyse the resulting matrices. If and only if the continuum hypothesis is correct will it be found that the factor loadings in both matrices will be similar or identical, and that these loading will be proportional to the degree to which the various tests discriminate between the two criterion groups.

An experiment has been reported, using this method. Using 100 normal controls, 50 schizophrenics and 50 manic-depressives, 20 objective tests which had been found previously to correlate with psychosis were applied to all the subjects (Eysenck, 1952b). The results clearly bore out the continuum hypothesis. The two sets of factor loadings correlated .87, and both were proportional to the differentiating power of the tests r = .90 and .95, respecti- vely). These figures would seem to establish the continuum hypotheses quite firmly; the results of the experiment are not compatible with a categorical type of theory.

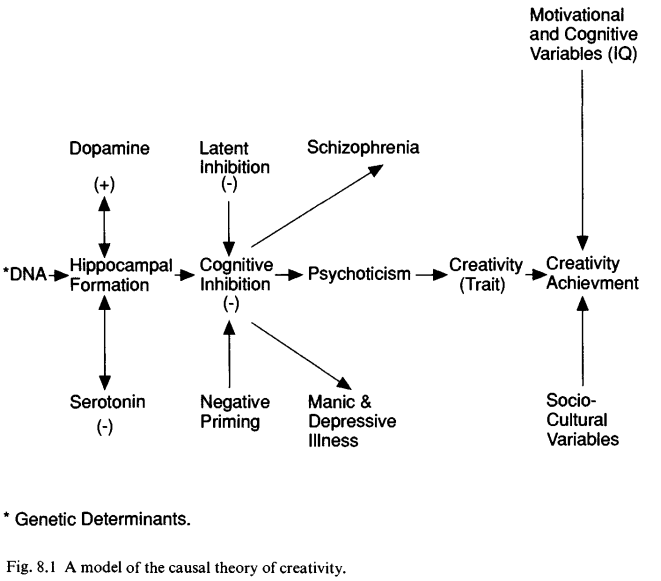

Eysenck summarizes his model:

Possessing this trait, however, does not guarantee creative achievement. Trait creativity may be a necessary component of such achievement, but many other conditions must be fulfilled, many other traits added (e.g. ego-strength), many abilities and behaviours added (e.g. IQ, persistence), and many socio- cultural variables present, before high creative achievement becomes prob- able. Genius is characterized by a very rare combination of gifts, and these gifts function synergistically, i.e. they multiply rather than add their effects. Hence the mostly normally distributed conditions for supreme achievement interact in such a manner as to produce a J-shaped distribution, with huge numbers of non- or poor achievers, a small number of high achievers, and the isolated genius at the top.

This, in very rough outline, is the theory here put forward. As discussed, there is some evidence in favour of the theory, and very little against it. Can we safely say that the theory possesses some scientific credentials, and may be said to be to some extent a valid account of reality? There are obvious weaknesses. Genius is extremely rare, and no genius has so far been directly studied with such a theory in mind. My own tests have been done to study deductions from the theory, and these have usually been confirmatory. Is that enough, and how far does it get us?

Terms like ‘theory’, of course, are often abused. Thus Koestler (1964) attempts to explain creativity in terms of his theory of’bisociation’ according to which the creative act ‘always operates on more than one plane’ (p. 36). This is not a theory, but a description; it cannot be tested, but acts as a definition. Within those limits, it is acceptable as a non-contingent proposition (Smets- lund, 1984), i.e. necessarily true and not subject to empirical proof. A creative idea must, by definition, bring together two or more previously unrelated concepts. As an example, consider US Patent 5,163,447, the ‘force-sensitive, sound-playing condom’, i.e. an assembly of a piezo-electric sound transducer, microchip, power supply and miniature circuitry in the rim of a condom, so that when pressure is applied, it emits ‘a predetermined melody or a voice message’. Here is bisociation in its purest form, bringing together mankind’s two most pressing needs, safe sex and eternal entertainment. But there is no proper theory here; nothing is said that could be disproved by experiment. Theory implies a lot more than simple description.

And he continues outlining his own theory of scientific progress:

The philosophy of science has thrown up several criteria for judging the success of a theory in science. All are agreed that it must be testable, but there are two alternative ways of judging the outcome of such tests. Tradition (including the Vienna school) insists on the importance of confirmation’, the theory is in good shape as long as results of testing deductions are positive (Suppe, 1974). Popper (1959, 1979), on the other hand, uses falsification as his criterion, pointing out that theories can never be proved to be correct, because we cannot ever test all the deductions that can possibly be made. More recent writers like Lakatos (1970, 1978; Lakatos and Musgrave, 1970) have directed their attention rather at a whole research programme, which can be either advancing or degenerating. An advancing research programme records a number of successful predictions which suggest further theoretical advances; a degenerating research programme seeks to excuse its failures by appealing to previously unconsidered boundary conditions. On those terms we are surely dealing with an advancing programme shift; building on research already done, many new avenues are opening up for supporting or disproving the theories making up our model.

It has always seemed to me that the Viennese School, and Popper, too, were wrong in disregarding the evolutionary aspect of scientific theories. Methods appropriate for dealing with theories having a long history of development might not be optimal in dealing with theories in newly developing fields, lacking the firm sub-structure of the older kind. Newton, as already men- tioned, succeeded in physics, where much sound knowledge existed in the background, as well as good theories; he failed in chemistry/alchemy where they did not. Perhaps it may be useful to put forward my faltering steps in this very complex area situated between science and philosophy (Eysenck, 1960, 1985b).

It is agreed that theories can never be proved right, and equally that they are dependent on a variety of facts, hunches and assumptions outside the theory itself; these are essential for making the theory testable. Cohen and Nagel (1936) put the matter very clearly, and take as their example Foucault’s famous experiment in which he showed that light travels faster in air than in water. This was considered a crucial experiment to decide between two hypotheses: H1? the hypothesis that light consists of very small particles travelling with enormous speeds, and H2 , the hypothesis that light is a form of wave motion. H1 implies the proposition Pl that the velocity of light in water is greater than in air, while H2 implies the proposition P2 that the velocity of light in water is less than in air. According to the doctrine of crucial experiments, the corpuscular hypothesis of light should have been banished to limbo once and for all. However, as is well known, contemporary physics has revived the corpuscular theory in order to explain certain optical effects which cannot be explained by the wave theory. What went wrong?

As Cohen and Nagel point out, in order to deduce the proposition P1 from H1 and in order that we may be able to perform the experiment of Foucault, many other assumptions, K, must be made about the nature of light and the instruments we employ in measuring its velocity. Consequently, it is not the hypothesis H1 alone which is being put to the test by the experiment – it is H1 and K. The logic of the crucial experiment may therefore be put in this fashion. If Hl and K, then P1; if now experiment shows P1 to be false, then either Hl is false or K (in part or complete) is false (or of course both may be false!). If we have good grounds for believing that K is not false, H1 is refuted by the experiment. Nevertheless the experiment really tests both H1 and K. If in the interest of the coherence of our knowledge it is found necessary to revise the assumptions contained in K, the crucial experiment must be reinterpreted, and it need not then decide against H1.

What I am suggesting is that when we are using H + K to deduce P, the ratio of H to K will vary according to the state of development of a given science. At an early stage, K will be relatively little known, and negative outcomes of testing H + K will quite possibly be due to faulty assumptions concerning K. Such theories I have called ‘weak’, as opposed to ‘strong’ theories where much is known about K, so that negative outcomes of testing H + K are much more likely to be due to errors in H (Eysenck, 1960, 1985b).

We may now indicate the relevance of this discussion to our distinction between weak and strong theories. Strong theories are elaborated on the basis of a large, well founded and experimentally based set of assumptions, K, so that the results of new experiments are interpreted almost exclusively in terms of the light they throw on H1, H2, …, Hn . Weak theories lack such a basis, and negative results of new experiments may be interpreted with almost equal ease as disproving H or disproving K. The relative importance of K can of course vary continuously, giving rise to a continuum; the use of the terms ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ is merely intended to refer to the extremes of this continuum, not to suggest the existence of two quite separate types of theories. In psychology, K is infinitely less strong than it is in physics, and consequently theories in psychology inevitably lie towards the weaker pole.

Weak theories in science, then, generate research the main function of which is to investigate certain problems which, but for the theory in question, would not have arisen in that particular form; their main purpose is not to generate predictions the chief use of which is the direct verification or confirmation of the theory. This is not to say that such theories are not weakened if the majority of predictions made are infirmed; obviously there comes a point when investigators turn to more promising theories after consistent failure with a given hypothesis, however interesting it may be. My intention is merely to draw attention to the fact – which will surely be obvious to most scientifically trained people – that both proof and failure of deductions from a scientific hypothesis are more complex than may appear at first sight, and that the simple-minded application of precepts derived from strong theories to a field like psychology may be extremely misleading. Ultimately, as Conant has emphasized, scientific theories of any kind are not discarded because of failures of predictions, but only because a better theory has been advanced.

The reader with a philosophy background will naturally think of this in terms of The Web of Belief, which takes us back to my earlier days of blogging philosophy!