It seems that no one has integrated this literature yet. I will take a quick stab at it here. It could be expanded into a proper paper later in case someone wants to and have time to do that.

Stereotypes

Lee Jussim (also blog) has done a tremendous job at reviewing the stereotype literature in recently years. In general he has found that stereotypes are mostly moderately to very accurate. On the other hand, self-fulfilling prophecies are probably real but fairly limited (e.g. work best when teachers don’t know their students well yet), especially in comparison to stereotype accuracy. Of course, these findings are exactly the opposite of what social psychologists, taken as a group, have been telling us for years.

The best short review of the literature is their book chapter The Unbearable Accuracy of Stereotypes. A longer treatment can be found in his 2012 book Social Perception and Social Reality: Why Accuracy Dominates Bias and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (libgen).

Occupational success and cognitive ability

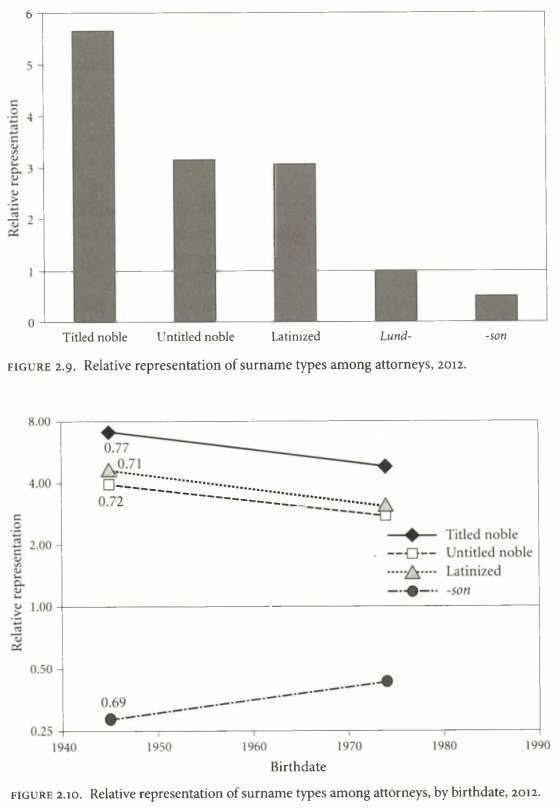

Society is more or less a semi-stable hierarchy biased on mostly inherited personality traits, cognitive ability as well as some family-based advantage. This shows up in the examination of surnames over time in many countries, as documented in Gregory Clark’s book The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility (libgen). One example:

Briefly put, surnames are kind of an extended family and they tend to keep their standing over time. They regress towards the mean (not the statistical kind!), but slowly. This is due to outmarrying (marrying people from lower classes) and genetic regression (i.e. predicted via breeder’s equation and due to the fact that narrow heritability and shared environment does not add up to 1).

It also shows up when educational attainment is directly examined with behavioral genetic methods. We reviewed the literature recently:

How do we find out whether g is causally related to later socioeconomic status? There are at least five lines of evidence: First, g and socioeconomic status correlate in adulthood. This has consistently been found for so many years that it hardly bears repeating[22, 23]. Second, in longitudinal studies, childhood g is a good correlate of adult socioeconomic status. A recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found that g was a better correlate of adult socioeconomic status and income than was parental socioeconomic status[24]. Third, there is a genetic overlap of causes of g and socioeconomic status and income[25, 26, 27, 28]. Fourth, multiple regression analyses show that IQ is a good predictor of future socioeconomic status, income and more, even controlling for parental income and the like[29]. Fifth, comparisons between full-siblings reared together show that those with higher IQ tend to do better in society. This cannot be attributed to shared environmental factors since these are the same for both siblings[30, 31].

I’m not aware of any behavioral genetic study of occupational success itself, but that may exist somewhere. (The scientific literature is basically a very badly standardized, difficult to search database.) But clearly, occupational success is closely related to income, educational attainment, cognitive ability and certain personality traits, all of which show substantial heritability and some of which are known to correlate genetically.

Occupations and cognitive ability

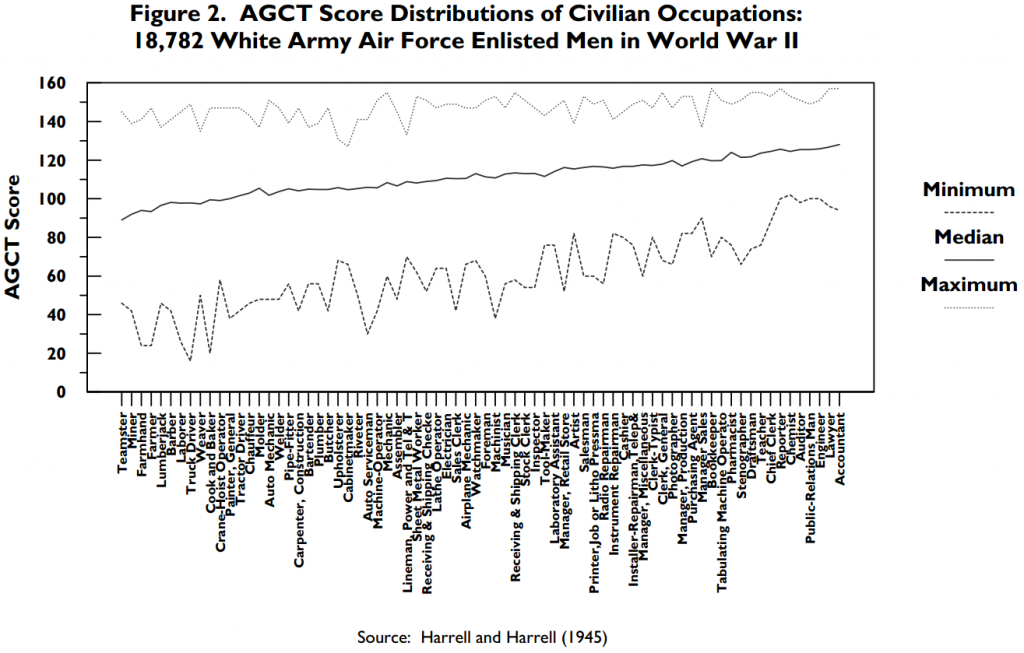

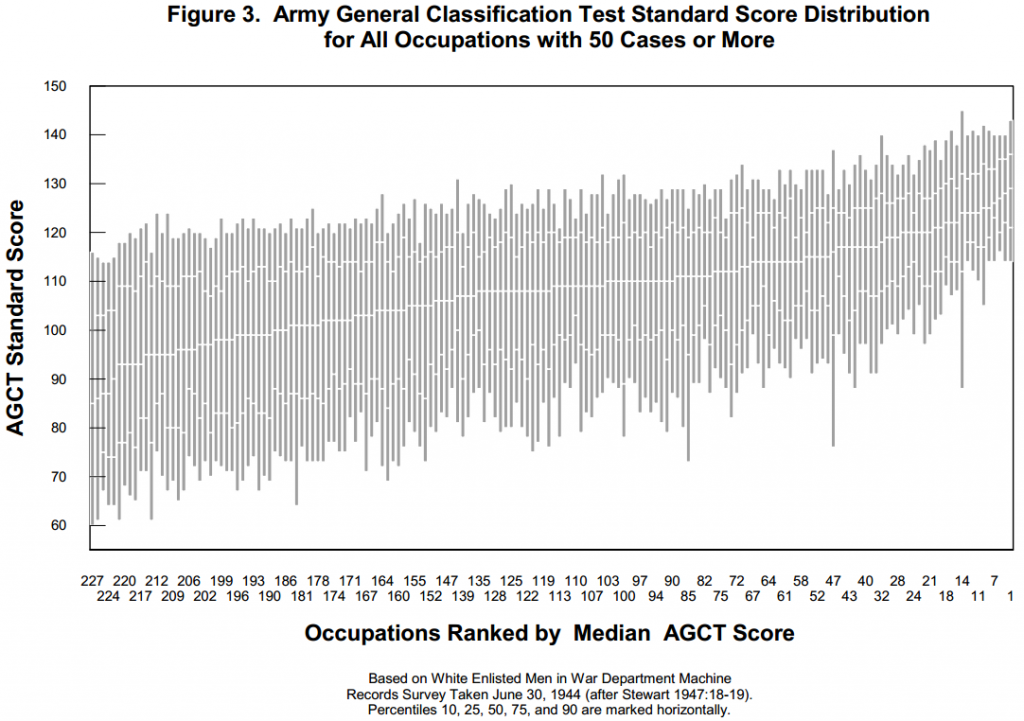

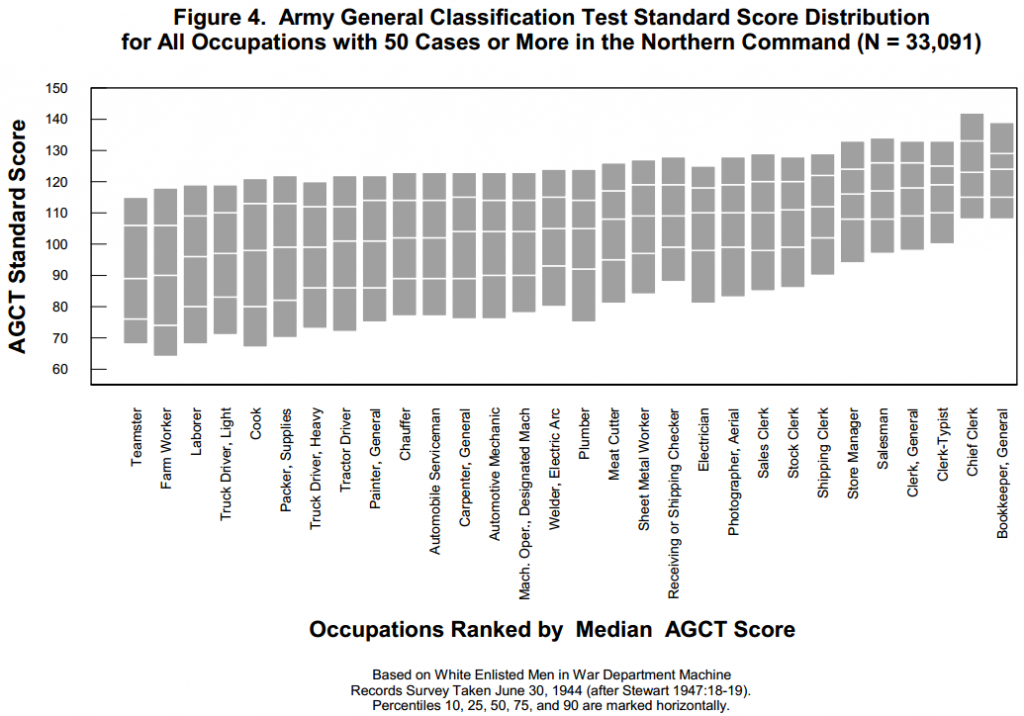

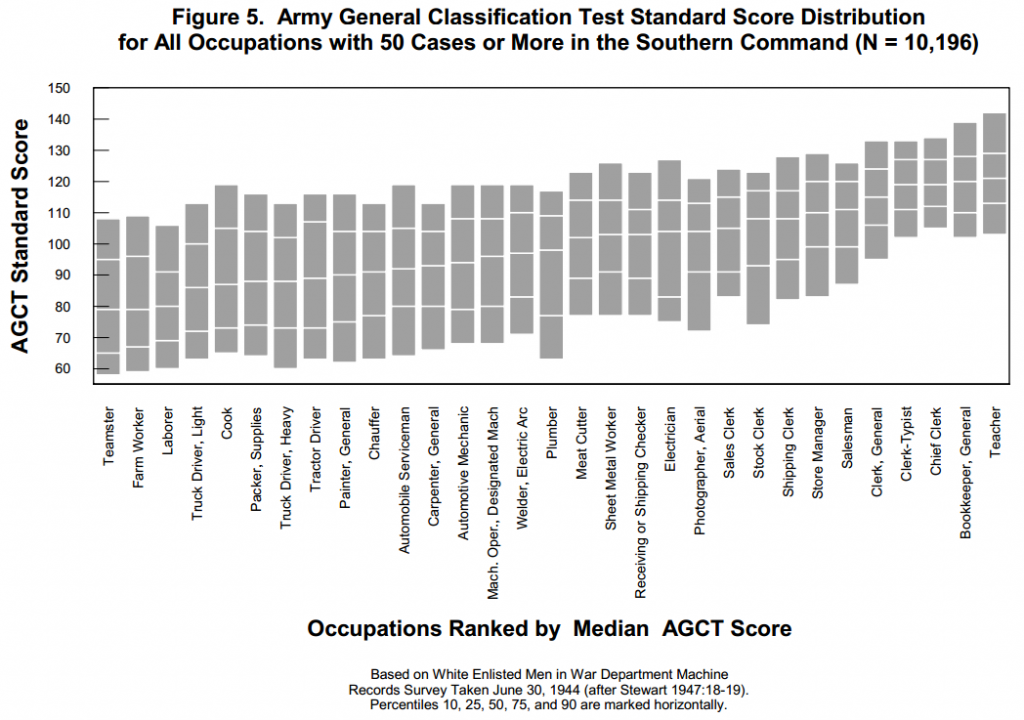

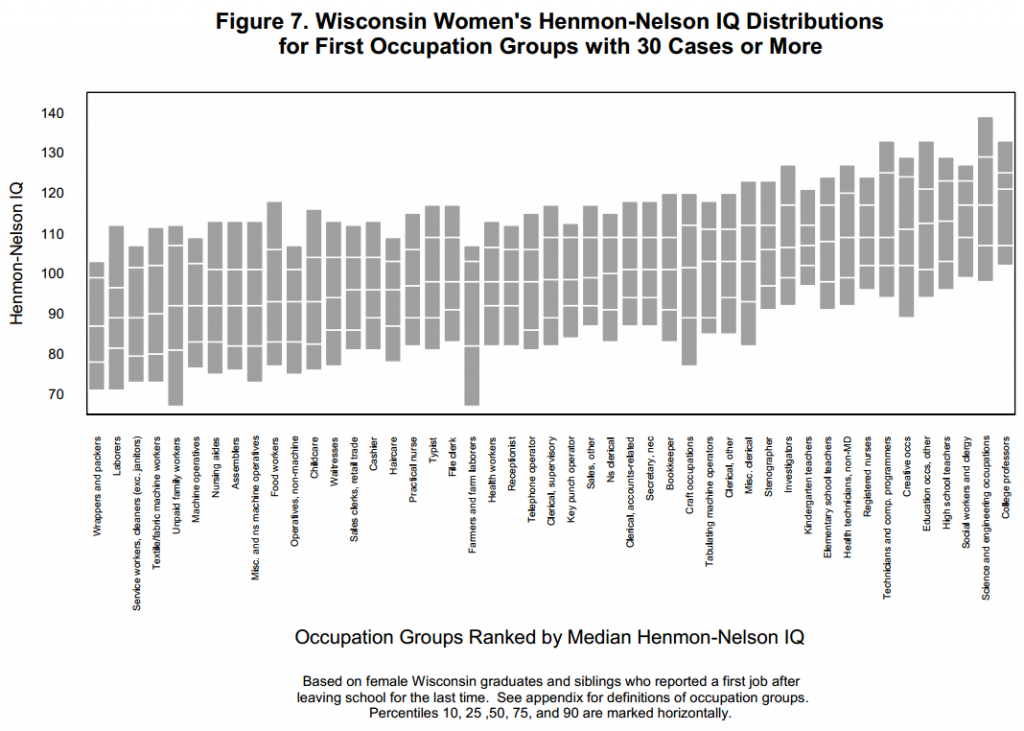

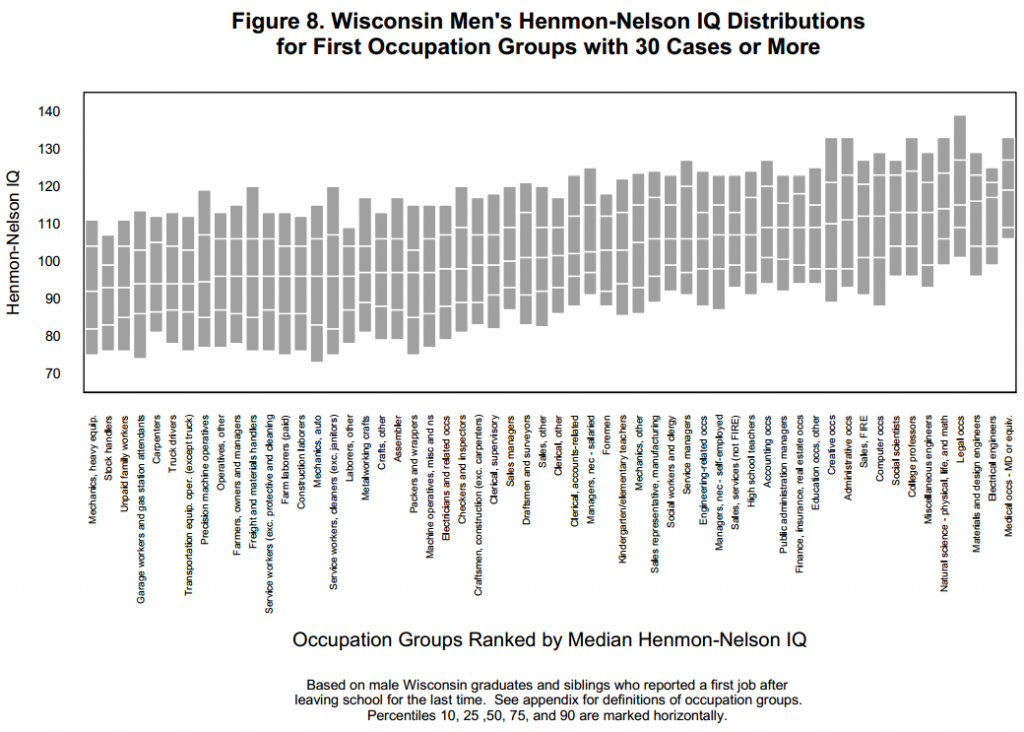

An old line of research shows that there is indeed a stable hierarchy in occupations’ mean and minimum cognitive ability levels. One good review of this is Meritocracy, Cognitive Ability,

and the Sources of Occupational Success, a working paper from 2002. I could not find a more recent version. The paper itself is somewhat antagonistic against the idea (the author hates psychometricians, in particular dislikes Herrnstein and Murray, as well as Jensen) but it does neatly summarize a lot of findings.

The last one is from Gottfredson’s book chapter g, jobs, and life (her site, better version).

Occupations and cognitive ability in preparation

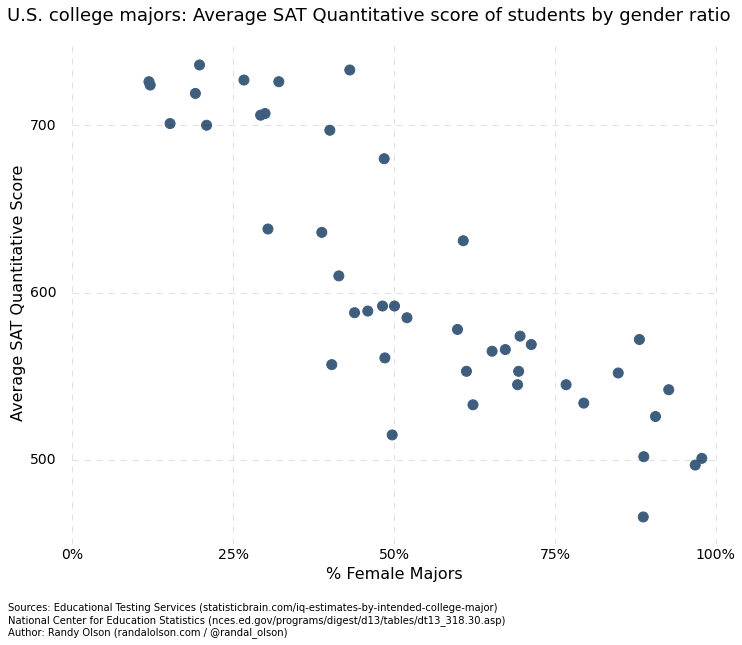

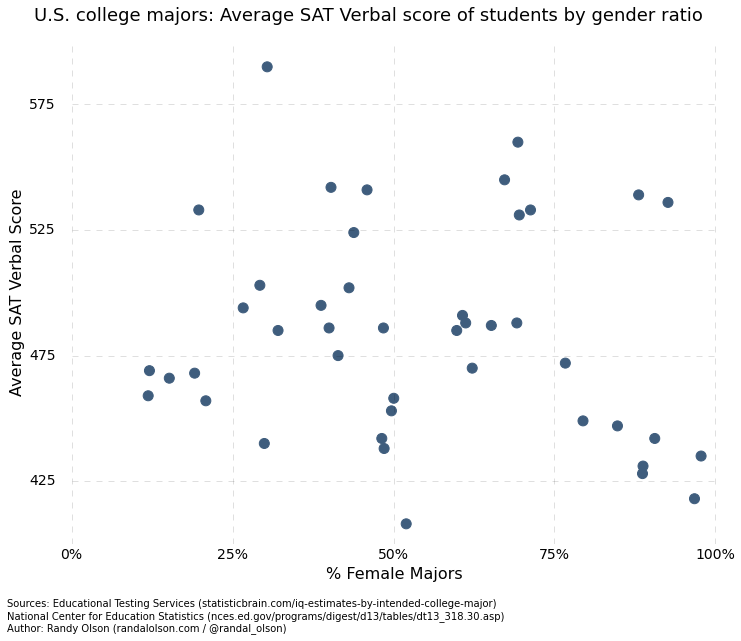

Furthermore, we can go a step back from the above and find SAT scores (almost an IQ test) by college majors (more numbers here). These later result in people working in different occupations, altho the connection is not always a simple one-to-one, but somewhere between many-to-many and one-to-one, we might call it a few to a few. Some occupations only recruit persons with particular degrees — doctors must have degrees in medicine — while others are flexible within limits. Physics majors often don’t work with physics at their level of competence, but instead work as secondary education teachers, in the finance industry, as programmers, as engineers and of course sometimes as physicists of various kinds such as radiation specialists at hospitals and meteorologists. But still, physicists don’t often work as child carers or psychologists, so there is in general a strong connection between college majors and occupations.

There is some stereotype research into college majors. For instance, a recently popularized study showed that beliefs about intellectual requirements of college majors correlated with female% of the field, as in, the harder fields perceived to be more difficult had fewer women. In fact, the perceived difficulty of the field probably just mostly proxies the actual difficulty of the field, as measured by the mean SAT/ACT score of the students. However, no one seems to have actually correlated the SAT scores with the perceived difficulty, which is the correlation that is the most relevant for stereotype accuracy research.

There is a catch, however. If one analyses the SAT subtests vs. gender%, one sees that it is mostly the quantitative part of the SAT that gives rise to the SAT x gender% correlation. One can also see that the gender% correlates with median income by major.

Stereotypes about occupations and their cognitive ability

Finally, we get to the central question. If we ask people to estimate the cognitive ability of persons by occupation and then correlate this with the actual cognitive ability, what do we get? Jensen summarizes some results in his 1980 book Bias in Mental Testing (p. 339). I mark the most important passages.

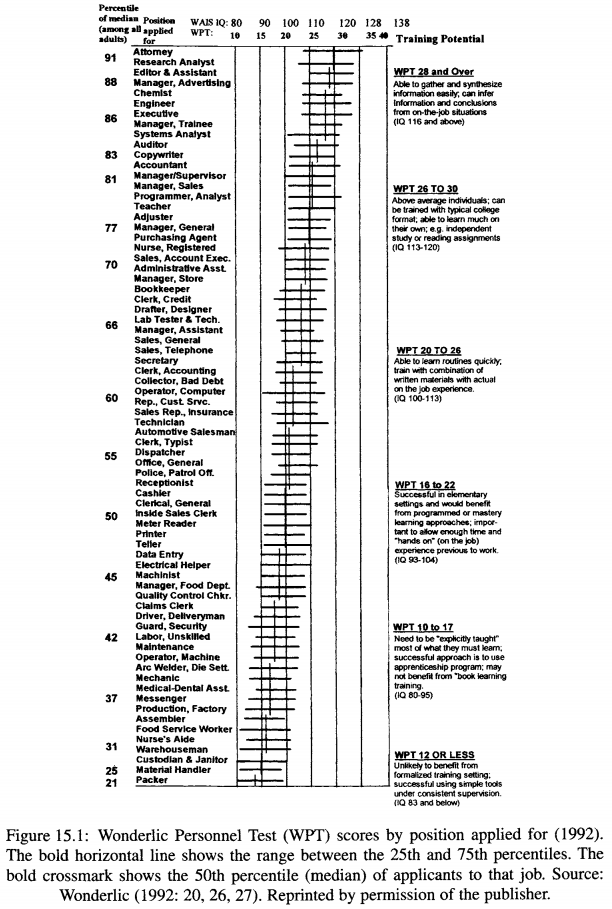

People’s average ranking of occupations is much the same regardless of the basis on which they were told to rank them. The well-known Barr scale of occupations was constructed by asking 30 “ psychological judges” to rate 120 specific occupations, each definitely and concretely described, on a scale going from 0 to 100 according to the level of general intelligence required for ordinary success in the occupation. These judgments were made in 1920. Forty-four years later, in 1964, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC), in a large public opinion poll, asked many people to rate a large number of specific occupations in terms of their subjective opinion of the prestige of each occupation relative to all of the others. The correlation between the 1920 Barr ratings based on the average subjectively estimated intelligence requirements of the various occupations and the 1964 NORC ratings based on the average subjective opined prestige of the occupations is .91. The 1960 U.S. Census o f Population: Classified Index o f Occupations and Industries assigns each of several hundred occupations a composite index score based on the average income and educational level prevailing in the occupation. This index correlates .81 with the Barr subjective intelligence ratings and .90 with the NORC prestige ratings.

Rankings of the prestige of 25 occupations made by 450 high school and college students in 1946 showed the remarkable correlation of .97 with the rankings of the same occupations made by students in 1925 (Tyler, 1965, p. 342). Then, in 1949, the average ranking of these occupations by 500 teachers college students correlated .98 with the 1946 rankings by a different group of high school and college students. Very similar prestige rankings are also found in Britain and show a high degree of consistency across such groups as adolescents and adults, men and women, old and young, and upper and lower social classes. Obviously people are in considerable agreement in their subjective perceptions of numerous occupations, perceptions based on some kind of amalagam of the prestige image and supposed intellectual requirements of occupations, and these are highly related to such objective indices as the typical educational level and average income of the occupation. The subjective desirability of various occupations is also a part of the picture, as indicated by the relative frequencies of various occupational choices made by high school students. These frequencies show scant correspondence to the actual frequencies in various occupations; high-status occupations are greatly overselected and low-status occupations are seldom selected.

How well do such ratings of occupations correlate with the actual IQs of the persons in the rated occupations? The answer depends on whether we correlate the occupational prestige ratings with the average IQs in the various occupations or with the IQs of individual persons. The correlations between average prestige ratings and average IQs in occupations are very high— .90 to .95—when the averages are based on a large number of raters and a wide range of rated occupations. This means that the average of many people’s subjective perceptions conforms closely to an objective criterion, namely, tested IQ. Occupations with the highest status ratings are the learned professions—physician, scientist, lawyer, accountant, engineer, and other occupations that involve high educational requirements and highly developed skills, usually of an intellectual nature. The lowest-rated occupations are unskilled manual labor that almost any able-bodied person could do with very little or no prior training or experience and that involves minimal responsibility for decisions or supervision.

The correlation between rated occupational status and individual IQs ranges from about .50 to .70 in various studies. The results of such studies are much the same in Britain, the Netherlands, and the Soviet Union as in the United States, where the results are about the same for whites and blacks. The size of the correlation, which varies among different samples, seems to depend mostly on the age of the persons whose IQs are correlated with occupational status. IQ and occupational status are correlated .50 to .60 for young men ages 18 to 26 and about .70 for men over 40. A few years can make a big difference in these correlations. The younger men, of course, have not all yet attained their top career potential, and some of the highest-prestige occupations are not even represented in younger age groups. Judges, professors, business executives, college presidents, and the like are missing occupational categories in the studies based on young men, such as those drafted into the armed forces (e.g., the classic study of Harrell & Harrell, 1945).

I predict that there is a lot of delicious low-hanging, ripe research fruit ready for harvest in this area if one takes a day or ten to dig up some data and read thru older papers, books and reports.