- Christainsen, Gregory. (2020). Rushton, Jensen, and the Wealth of Nations: Biogeography and Public Policy as Determinants of Economic Growth. Mankind Quarterly.

This paper offers a review of some of the empirical literature on economic growth and discusses its recent evolution in light of developments in intelligence research and genomics. The paper also undertakes the first regression analysis of economic growth to use the most up-to-date version (V1.3.2) of David Becker’s data set of international IQ scores. The analysis concerns the growth of 94 countries from 1995-2016. The new regression analysis replicates the results of Jones and Schneider (2006) in finding IQ to have a robust impact on economic growth. Political and economic institutions are represented in the regressions via a country’s “degree of capitalism” (aka “economic freedom”), which is found to have an impact that is positive and statistically significant. A change from communism to a market economy does much to increase growth, but the paper finds diminishing returns to free markets. Countries whose people are mostly of sub-Saharan African descent have low average IQ scores, but the paper finds that other factors also have lessened economic growth not only in Africa, but in Haiti and Jamaica as well. Rushton and Jensen (2005, 2010) put forth the hypothesis that average IQ differences across ethnic groups are 50% due to genetic differences, and 50% due to differences in natural and social environments. Applied to international IQ scores, the paper finds the hypothesis to be very reasonable.

Key Words: Intelligence, Biogeography, Institutions, Economic growth, Causation, Brain size, Genomics

This piece was originally penned for our suppressed Special Issue at MDPI’s Psych journal. The Special Issue was about 70% completed when SJWs succeeded in having it halted, and the papers in review were then stuck in limbo. Some of them are still finding a new home. This was one of these papers. MDPI, or their new editor, has hidden the Special Issue on the website of the journal, but if one has a direct link, it still works (archived).

Some readers might recall Christainsen from before, and they would be right. In 2013, he published a similar paper in Intelligence:

-

Christainsen, G. B. (2013). IQ and the wealth of nations: How much reverse causality?. Intelligence, 41(5), 688-698.

This paper uses data from 130 IQ test administrations worldwide and employs regression analysis to try to quantify the impact of living conditions on average IQ scores in nationally-representative samples. The study emphasizes the possible role of conditions at or near the test-takers’ time of birth. The paper finds that the impact of living conditions is of much smaller magnitude than is suggested by just looking at correlations between average IQ scores and socioeconomic indicators. After controlling for test-takers’ region of ancestry, the impact of parasitic diseases on average IQ is found to be statistically insignificant when test results from the Caribbean are included in the analysis. As far as IQ and the wealth of nations are concerned, causality thus appears to run mostly from the former to the latter. The test-takers’ region of ancestry dominates the regression results. While differences in average scores worldwide can thus be plausibly viewed as being influenced by genetic differences across world regions, it is also possible that score differences are influenced by regional differences in culture that are independent of genetic factors. Differences in average IQ across world regions may change in the years ahead insofar as the strength of Flynn effects may not be uniform, but some regional differences in average g levels seem likely to continue indefinitely.

Christainsen is to be commended for being properly forthright about these issues. Economists are all about quantitative rigor, but they quickly get mealymouthed when it comes to clarifying just what it is their precious human capital term refers to, and how heritable it is. Garrett Jones deserves some recognition for attempting to get a little bit more serious about this with his popular science book The Hind Mind, but he was also intentionally unprovocative — or maybe wise!

So back to the new paper. It takes a typical economic modeling approach and uses the new Becker IQs (these can always be found at Becker’s site: https://viewoniq.org/). As I have pointed out before, the Becker IQs, though methodologically superior to Lynn’s older ones, are still based on less data, and so actually tends to perform somewhat worse in analyses. By my count, Becker has so far incorporated about 70% of Lynn’s sources, and has not begun incorporating those that Jason Malloy so skillfully dug up over the years before his inactivity. Still, considering this is a work in progress, mostly by a single man with no serious funding, then a lot of progress have been made. God bless German diligence. Christainsen’s main regressions look like this:

The coefficient for average IQ in the regression for the core data set is 0.1795, disregarding for now the variable referring to additional opportunities for rapid growth that less-developed, high-IQ countries may have. The coefficient for IQ is somewhat higher here than the estimate of Garett Jones (0.11). A logarithmic specification for IQ does not fit the data very well, suggesting that IQ does not suffer from diminishing returns in its effects on economic growth.

The coefficient for average IQ in the regression involving the 45 countries with acceptable pre-2000 IQ data (0.1815) is similar to the one for the core data set, indicating that a regression almost completely devoid of reverse causality nevertheless shows a strong relationship between IQ and growth. The coefficient is statistically significant at a 0.1 percent level. The association between IQ (adjusted for Flynn effects) and economic growth is therefore viewed as a causal relationship, with most of the causation going from the former to the latter. Garett Jones (2012) obtained the same kind of result with pre-1970 IQ scores. In another study, Christainsen (2013) found statistically significant reverse causality (beyond standard Flynn effects), but only of a modest magnitude.

The reader might be wondering whether this kind of result is limited to a few rogue economists, and no, it is not. Only the degree of frankness is. Here’s what two eminent economists wrote in 2012:

-

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2012). Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. Journal of economic growth, 17(4), 267-321.

We develop a new metric for the distribution of educational achievement across countries that can further track the cognitive skill distribution within countries and over time. Cross-country growth regressions generate a close relationship between educational achievement and GDP growth that is remarkably stable across extensive sensitivity analyses of specification, time period, and country samples. In a series of now-common microeconometric approaches for addressing causality, we narrow the range of plausible interpretations of this strong cognitive skills-growth relationship. These alternative estimation approaches, including instrumental variables, difference-in-differences among immigrants on the U.S. labor market, and longitudinal analysis of changes in cognitive skills and in growth rates, leave the stylized fact of a strong impact of cognitive skills unchanged. Moreover, the results indicate that school policy can be an important instrument to spur growth. The shares of basic literates and high performers have independent relationships with growth, the latter being larger in poorer countries.

So they call it “educational achievement”, but they are really just talking about PISA-like scholastic tests, and we know of course that these are practically intelligence tests at the country level.

They provide some historical background, probably of interest to readers so I quote at length:

As a simple summary observation, world policy attention today focuses on the lagging fortunes of Sub-Saharan Africa and of Latin America. Considerably less attention goes to East Asia, and, if anything, East Asia is proposed as a role model for the lagging regions. Yet to somebody contemplating development policy in the 1960s, none of this would be so obvious. Latin America had average income exceeding that in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa regions, and both of these exceeded East Asia (see Appendix Table 8). Further, Latin America had schooling levels that exceeded those in the others, which were roughly equal. Thus, on the basis of observed human capital investments, one might have expected Latin America to pull even farther ahead while having no strong priors on the other regions. The unmistakable failure of such expectations, coupled with a similar set of observations for separate countries in the regions, suggests skepticism about using human capital policies to foster development. But, this skepticism appears to be more an outgrowth of imperfect measurement of human capital investments than an empirical reality.

The measurement issues become apparent when we introduce direct measures of cognitive skills from international tests of math and science into the growth picture. The entire picture changes. Figure 1 plots regional growth in real per capita GDP between 1960 and 2000 against average test scores after conditioning on initial GDP per capita in 1960.3 Regional annual growth rates, which vary from 1.4% in Sub-Saharan Africa to 4.5% in East Asia, fall on a straight line with an R2 = 0.985. But, school attainment, when added to this regression, is unrelated to growth-rate differences. Figure 1 suggests that, conditional on initial income levels, regional growth over the last four decades is completely described by differences in cognitive skills.

In the upsurge of empirical analyses of why some nations grow faster than others since the seminal contributions by Barro (1991, 1997) and Mankiw et al. (1992), a vast literature of cross-country growth regressions has tended to find a significant positive association between quantitative measures of schooling and economic growth.4 But, all analyses using average years of schooling as the human capital measure implicitly assume that a year of schooling delivers the same increase in knowledge and skills regardless of the education system. For example, a year of schooling in Peru is assumed to create the same increase in productive human capital as a year of schooling in Japan. Equally as important, this measure assumes that formal schooling is the primary source of education and that variations in the quality of nonschool factors have a negligible effect on education outcomes.

In this paper, we concentrate directly on the role of cognitive skills. This approach was initiated by Hanushek and Kimko (2000), who related a measure of educational achievement derived from the international student achievement tests through 1991 to economic growth in 1960–1990 in a sample of 31 countries with available data. They found that the association of economic growth with cognitive skills dwarfs its association with years of schooling and raises the explanatory power of growth models substantially. Their general pattern of results has been duplicated by a series of other studies over the past 10 years that pursue different tests and specifications along with different variations of skills measurement.

The 2000 paper is interesting because it actually precedes Lynn’s 2002 book (IQ and the Wealth of Nations) that caused a big stir about national IQs. Lynn, however, has been collecting national IQ data since the 1970s, as I wrote in my review of his latest book with Becker. Lynn, however, did not attempt to do any regression modeling of economic growth early on, which is a pity because he had the chance to beat the economists at their own game by decades.

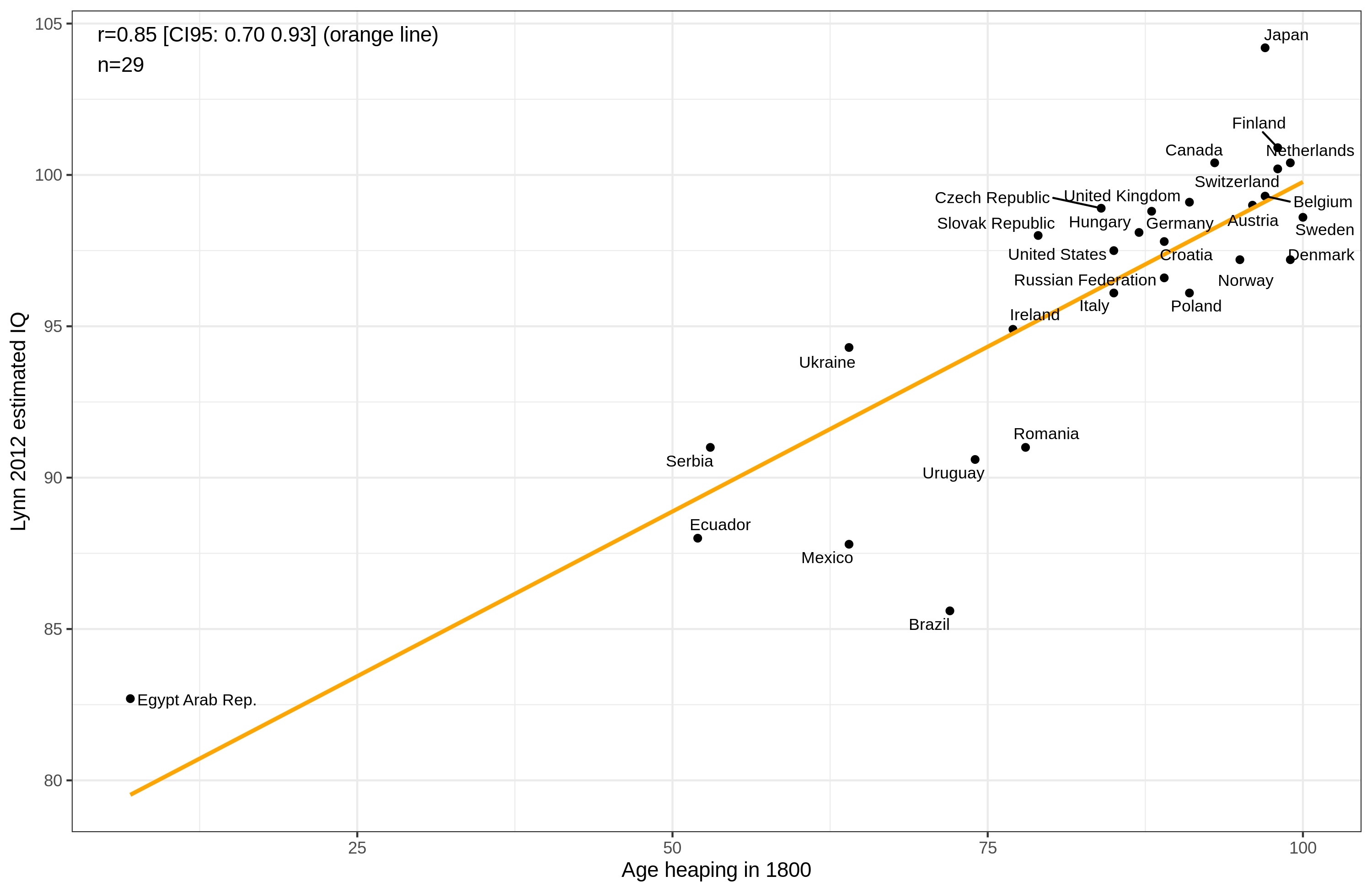

If we go back to the Christainsen paper, the main evidence we can give for lack of reverse causality concerns having IQ data measured before the growth period examined. In his case, he looks at the growth from 1995 to 2016 (~20 years), and his model 3 uses test data from before 2000, to mostly avoid possibility of reverse causality. However, this subsetting leads to a reduced sample size of 45, which is not at all satisfactory for that many included predictors. Worse, we know that the data coverage is worse for worse countries, so doing subsetting like this leads to restriction of range, and non-random missing data issues. So what is needed is more work on finding old IQ data so that one can expand the countries and times covered. As I have pointed out a long time ago, there are great datasets that no one has used for this purpose, also collected by economists, called age heaping (tendency for innumerate people to round ages to nearest 5 or 10). Historical estimates of cognitive ability go back to the middle ages based on this. Perhaps further yet, as it has been some years since I reviewed this literature. Age heaping, a simple measure of mathematical ability, measured in ~1800 correlates a respectable .85 with Lynn’s 2012 IQs, n = 29. Looks like this:

The main problem with age heaping is that it is essentially a single item IQ test, and we get the pass rate by country (sometimes by subnational regions too). Because it is easy, the smart countries tend to max out quite soon in the time series, making it useless to measure differences between them (in the above plot, many good countries are close to ~100% already by 1800). If one ignores this, one gets a massive ceiling problem that lowers the correlations (more apparent in e.g. the age heaping data for 1900).

There are other approaches as well. One can estimate cognitive ability from written texts, legal documents (ability to sign own name in population is a crude literacy measure), or any kind of deep survey data (which begin perhaps before IQ data, and cover more political units), because intelligence has certain patterns in the data one should be able to use, as discussed recently (also at the individual level). One could also get bold and use polygenic scores. I suggest one starts a large project of digging up old graveyards from all time periods to track the changes of polygenic scores over time, the same way it is currently being done for ancient genomics. Yes, the current genetic models have some bias for this purpose, but it won’t be like that forever. Before we get this genetic data, one can use old skulls which provide brain size measures, which should relate to intelligence levels at the time (see this paper).

Finally, while we are on this topic. Another old MQ paper worth reading on this topic:

-

Wong, B. (2007). Cognitive ability (IQ), education quality, economic growth, human migration: Implications from a sociobiological paradigm of global economic inequality. Mankind Quarterly, 48(1), 3.

Modernization theories propose that third world developing nations will eventually undergo a transformational process where they will go from traditional agrarian societies to industrialized ones, eventually reaching the development levels of Western, first world nations. It remains to be explained why industrialization has worked for only a small handful of European and Pacific Rim countries and has failed for most other nations of the world in South Asia, the Pacific Islands, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa. The 2007 World Bank Report Education Quality and Economic Growth demonstrates that education quality and cognitive skills, measured by international standardized test scores, are stronger predictors for national economic growth than educational quantity, measured by years of schooling and enrollment rates. This paper summarizes key findings of the World Bank report and finds that the intelligence quotient (IQ) is highly correlated with international standardized test scores and other indices that complement income levels as indicators of national well-being. As IQ is substantially heritable, blunt strategies directed at simple resource expansions or institutional changes are unlikely to be effective at reducing disparities in international cognitive skills. Imminent workable solutions geared towards reducing global economic inequalities continue to remain elusive. Implications from the consequences of global inequality are discussed in the context of 21st century human migration in the West and Northeast Asia.