Back in May 2020, I published a paper provocatively titled Mental Illness and the Left. It was based on the common observation (stereotype!) that conservatives seem less prone to mental illness. So OK, is this stereotype true too? I looked in the General Social Survey (GSS) dataset, a large long-running public dataset of representative US adults:

It has been claimed that left-wingers or liberals (US sense) tend to more often suffer from mental illness than right-wingers or conservatives. This potential link was investigated using the General Social Survey cumulative cross-sectional dataset (1972-2018). A search of the available variables resulted in 5 items measuring one’s own mental illness (e.g., ”Do you have any emotional or mental disability?”). All of these items were weakly associated with left-wing political ideology as measured by self-report, with especially high rates seen for the “extremely liberal” group. These results mostly held up in regressions that adjusted for age, sex, and race. For the variable with the most data (n = 11,338), the difference in the mental illness measure between “extremely liberal” and “extremely conservative” was 0.39 d. Temporal analysis showed that the relationship between mental illness, happiness, and political ideology has existed in the GSS data since the 1970s and still existed in the 2010s. Within-study meta-analysis of all the results found that extreme liberals had a 150% increased rate of mental illness compared to moderates. The finding of increased mental illness among left-wingers is congruent with numerous findings based on related constructs, such as positive relationships between conservatism, religiousness and health in general.

The study proved very popular, making the rounds on various right-wing websites. It currently has some 150k+ clicks on ResearchGate (most unfortunately to the preprint version). Since my study was published, replications have come out. The fact that this replicates is not at all surprising because the samples were very large, representative, and results not p-hacked and with tiny p values. Here’s an overview of recent replications:

- Bernardi, L. (2021). Depression and political predispositions: almost blue?. Party Politics, 27(6), 1132-1143.

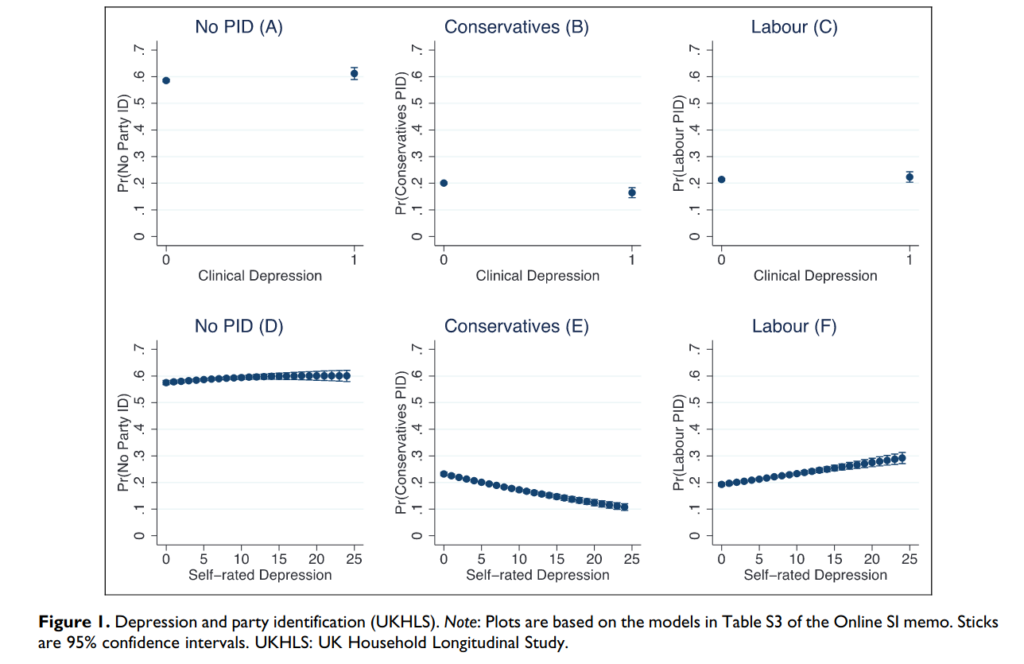

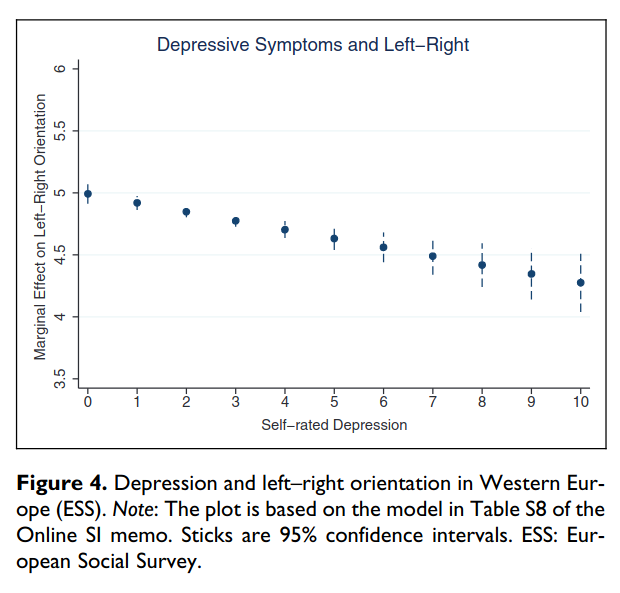

This article explores the relationship between depression—one of the most common mental health problems in our societies—and political predispositions. Drawing on cross-disciplinary research from psychology, psychiatry, and political science, the article uses data from Understanding Society and the European Social Survey to test this relationship with party identification, vote intentions and left–right orientation, and two different measures of self-rated clinical depression and depressive symptoms. Empirical analyses find a modest but significant, common tendency: individuals vulnerable to depression are less likely to identify with mainstream conservative parties, to vote for them, or to place themselves on the right side of the political spectrum (a “bias against the right”). No clear evidence is found that they also identify less with political parties. These findings contribute to our understanding of differences in political predispositions and raise important implications for political engagement.

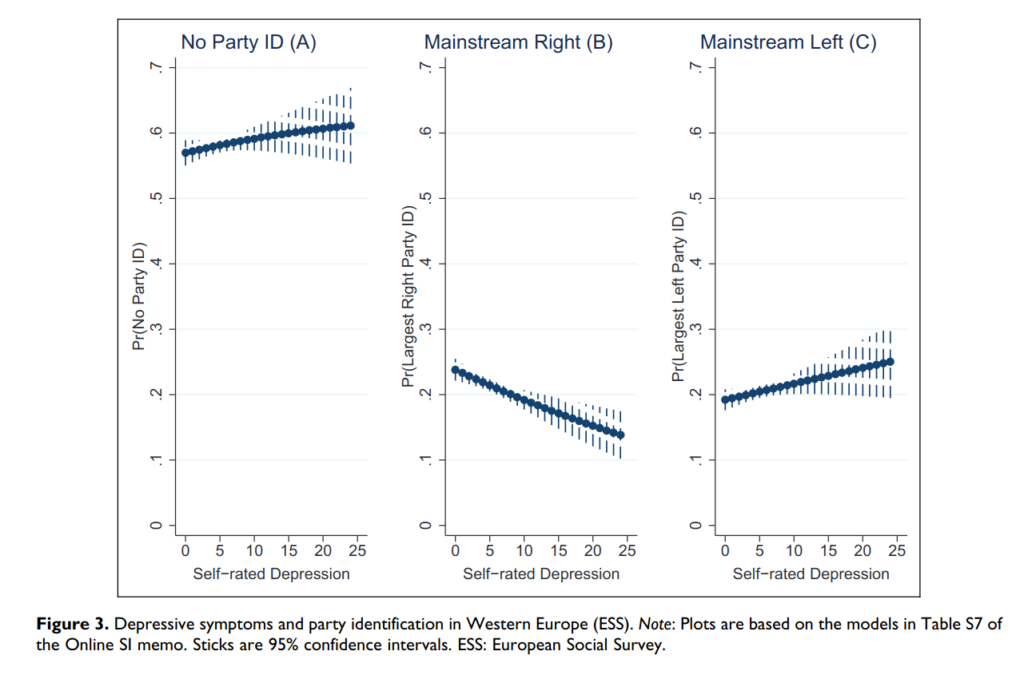

Bernardi relied on two large representative samples, and was mainly interested in depressive symptoms. Here’s the figures:

This is from the massive UKHLS study more commonly called the Understanding Society dataset. It describes itself as “Understanding Society is the largest longitudinal household panel study of its kind and provides vital evidence on life changes and stability”. Sample sizes:

Understanding Society is built on the successful British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) which ran from 1991-2009 and had around 10,000 households in it. Understanding Society started in 2009 and interviewed around 40,000 households, including around 8,000 of the orginal BHPS households. The inclusion of the BHPS households allows researchers and policy makers to track the lives of these households from 1991.

OK, seems legit, next sample:

And

This is based on the European Social Survey, another nice, huge, multi-national public dataset. As you can see, it doesn’t matter so much how one operationalizes the relationship, whether self-placement or relationship to bigger left vs. right parties.

- Kwon, S. (2022). The interplay between partisanship, risk perception, and mental distress during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1-17.

COVID-19 is a profoundly partisan issue in the U.S., with increasing polarization of the Republicans’ and Democrats’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and their precautionary actions to reduce virus transmission. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether and how partisan gaps in many aspects of the pandemic are linked to mental health, which has increasingly been a major concern. This study examined the association between political partisanship and mental health by assessing the mediating and moderating relationships between risk perception, expected infection severity of COVID-19, and partisanship in terms of mental health during the early stages of the pandemic. The data were drawn from a cross-sectional web survey conducted between March 20 and 30, 2020, with a sample of U.S. adults (N = 4,327). Of those participants, 38.9% and 29.6% were Democrats and Republicans, respectively. The results indicate that Democrats were more likely to experience COVID-induced mental distress than Republicans, and higher risk perception and expected infection severity were associated with mental distress. Furthermore, risk perception and expected infection severity of COVID-19 mediated approximately 24%–34% of the associations between political partisanship and mental distress. Finally, the adverse mental health impact of risk perception and expected infection severity appeared to be much stronger for Republicans than Democrats. The findings suggest that political partisanship is a key factor to understanding mental health consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S.

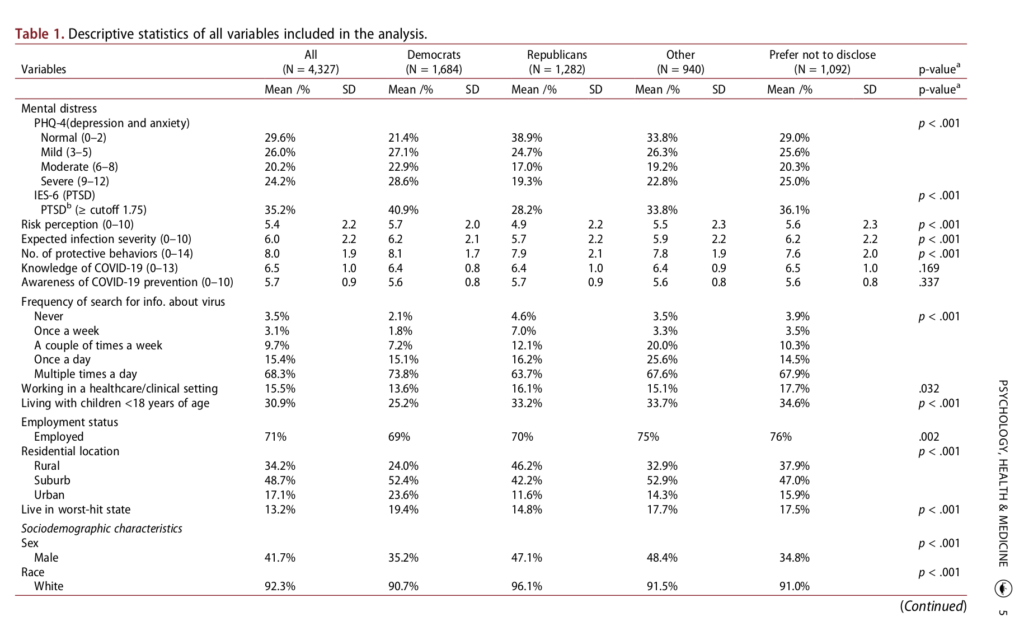

This one is pretty interesting given the times and attention to this topic. It replicates the usual pattern using symptom scales of distress:

Compare the means of Democrats vs. Republicans for the various mental distress cutoffs.

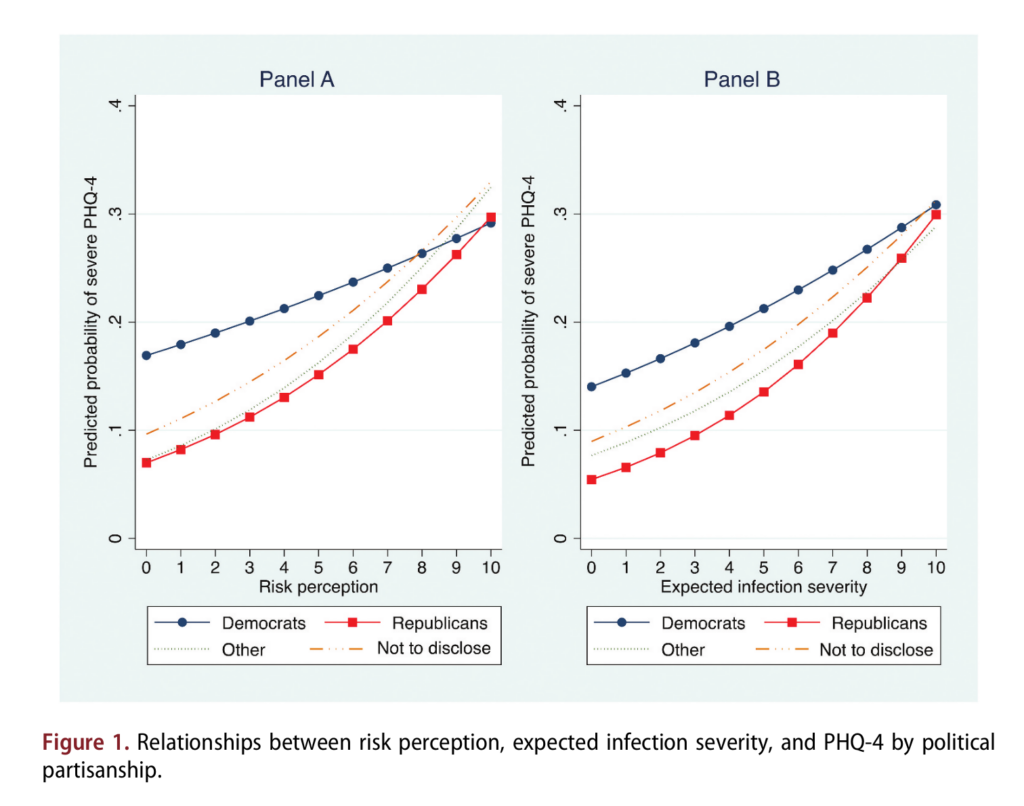

The most exotic thing they find is that in regression modeling controlling for lots of other stuff, distress is easier to predict based on risk perception in Republicans!

The models show that Republicans start out with lower levels of distress (as in the table before) but they rise more with increase risk perception and will equal their equally distressed Democrat panicers.

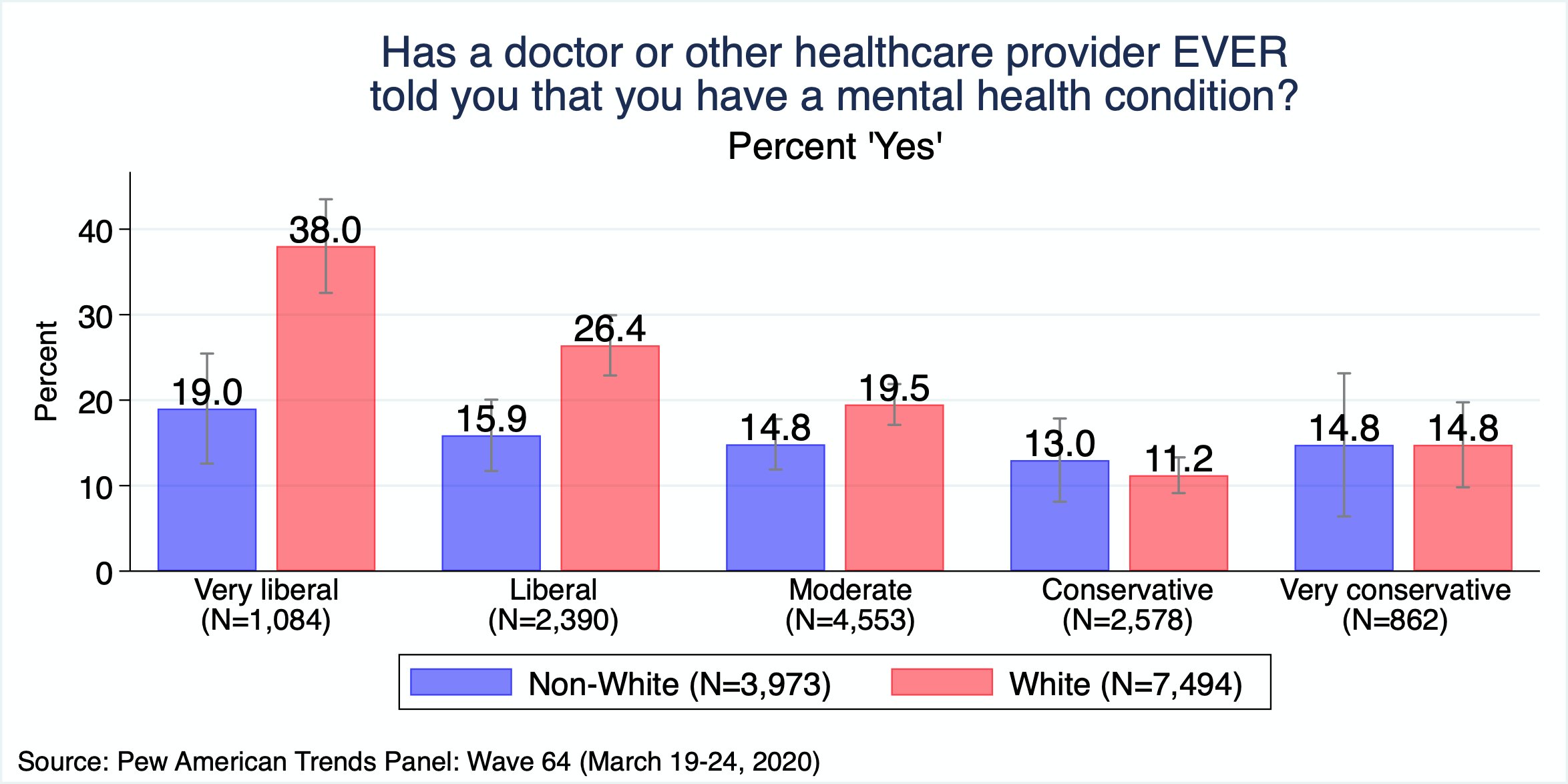

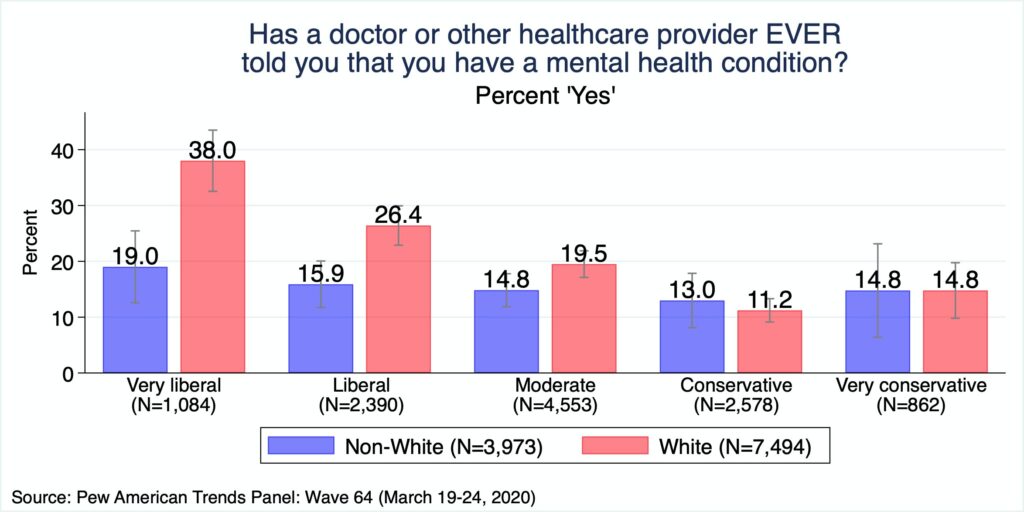

Not exactly a published study (codeword for Twitter thread of pre-preprint results), but Zach Goldberg, of media wokeness fame, had a look at some American survey data, and found the political association is particularly striking for White/Europeans:

The entire Twitter thread is worth reading. It proved so popular that some lame take-down attempt was written by some journalist with the most ironic title of all: Right wing media in USA love pseudoscience. 🤣

Older studies worth mentioning

This study is pretty funny:

- Van Hiel, A., & De Clercq, B. (2009). Authoritarianism is good for you: Right‐wing authoritarianism as a buffering factor for mental distress. European Journal of personality, 23(1), 33-50.

Although common knowledge seems to agree that authoritarianism is ‘bad to the self’, previous studies yielded inconclusive results with respect to the relationship between authoritarianism and mental distress. The present research explores whether the impact of facilitators of mental distress on actual mental distress depends on the level of authoritarianism. Study 1 includes a sample of 132 adults and demonstrated less negative consequences of D-type personality on depression for individuals with high rather than low levels of authoritarianism. Study 2 conducted in a sample of 109 elderly revealed that the effects of negative stressful life events on mental distress were curbed by higher levels of authoritarianism. It is concluded that while previous studies have amply shown that authoritarianism has adverse consequences for other people, these negative effects do not appear to be particularly present for the self.

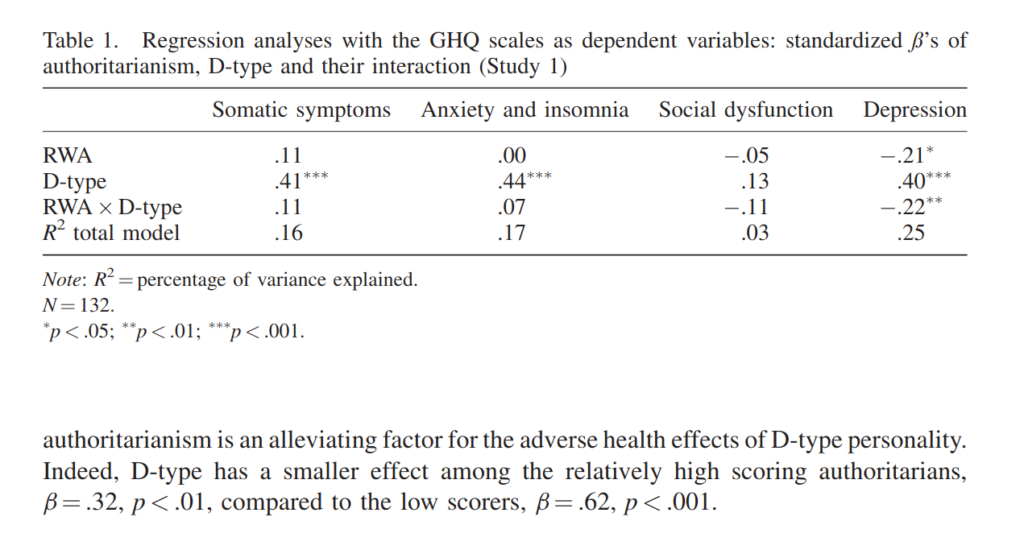

OK, tiny samples, but are the stats legit looking?

Their sample is too small for this stuff, and their model doesn’t make any sense to me. RWA is the familiar if broken right-wing authoritarianism scale. D-type is basically a measure of depression. The outcome is also measures of mental illness symptoms using the general health questionnaire, which includes depression symptoms. So why are they trying to predict depression from depression? I don’t know, but they do find that RWA relates negatively to depression at p < .05 (shrug tier), depression predicts depression at p < .001 (no surprise there), and there is an interaction so that RWA seemingly protects against depression being predicted from depression. This doesn’t make any sense to me but p < .01, so they could be on to something. Maybe. The study has 100+ citations, so I guess someone (exercise for the reader) could look over the citing studies to see if there are any extensions or replications.

- Schlenker, B. R., Chambers, J. R., & Le, B. M. (2012). Conservatives are happier than liberals, but why? Political ideology, personality, and life satisfaction. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 127-146.

Political conservatives are happier than liberals. We proposed that this happiness gap is accounted for by specific attitude and personality differences associated with positive adjustment and mental health. In contrast, a predominant social psychological explanation of the gap is that conservatives, who are described as fearful, defensive, and low in self-esteem, will rationalize away social inequalities in order to justify the status quo (system justification). In four studies, conservatives expressed greater personal agency (e.g., personal control, responsibility), more positive outlook (e.g., optimism, self-worth), more transcendent moral beliefs (e.g., greater religiosity, greater moral clarity, less tolerance of transgressions), and a generalized belief in fairness, and these differences accounted for the happiness gap. These patterns are consistent with the positive adjustment explanation.

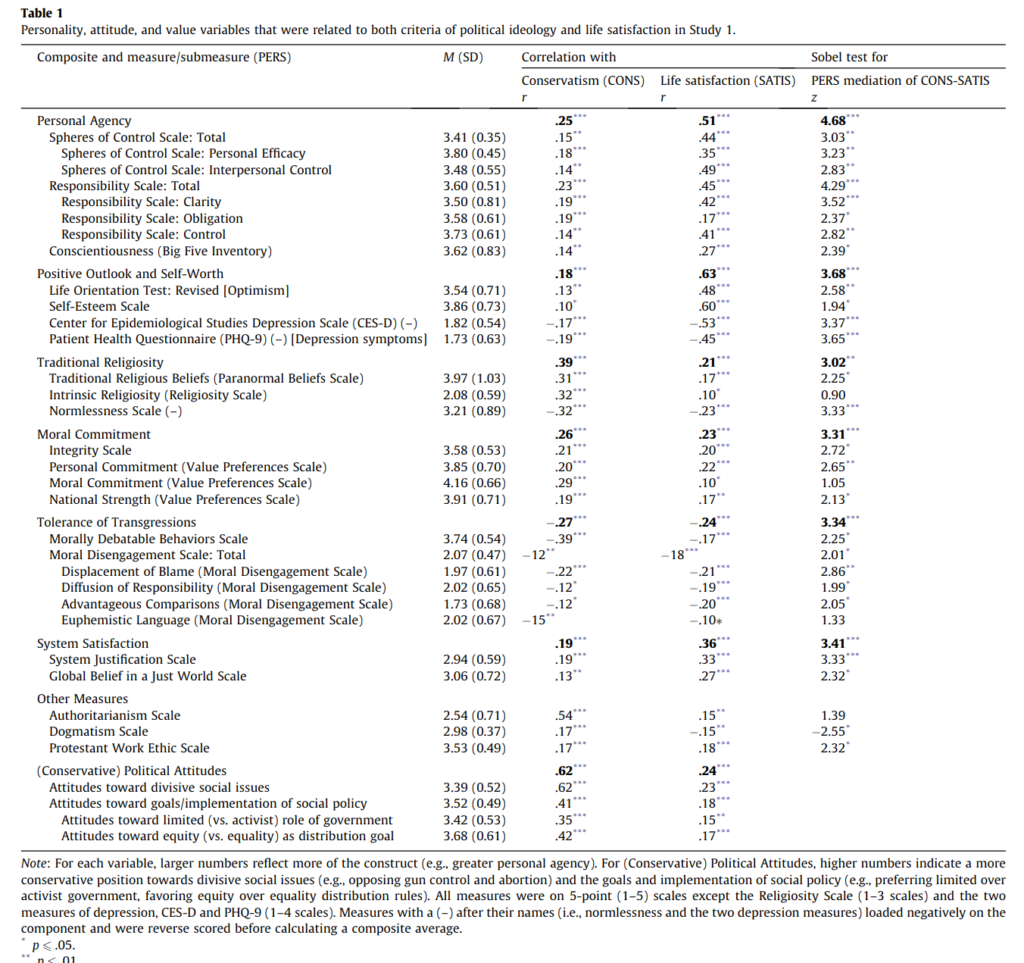

A review article that speculates on causes, and test some of them. This is actually an impressive article that studies 4 different datasets and overlaps with my study. First sample is an extensive survey of some 400 university students. Their table:

The theory the socialists have is that people who believe in meritocracy, general social fairness (“system justification scale”) are people who are deluded about Real Causes™ according to socialism, and these people are happier through their delusions. This stuff is mainly advocates by a guy called John T. Jost. He is maybe not coincidentally one of the social psychologists with the worst replication index score based on p values in published studies, ranking 65 out of 71.

Anyway, their next sample is the US subset of adults in the World Values Survey (WVS). The third one is the GSS, the same dataset I used 8 years later.

They say of their results:

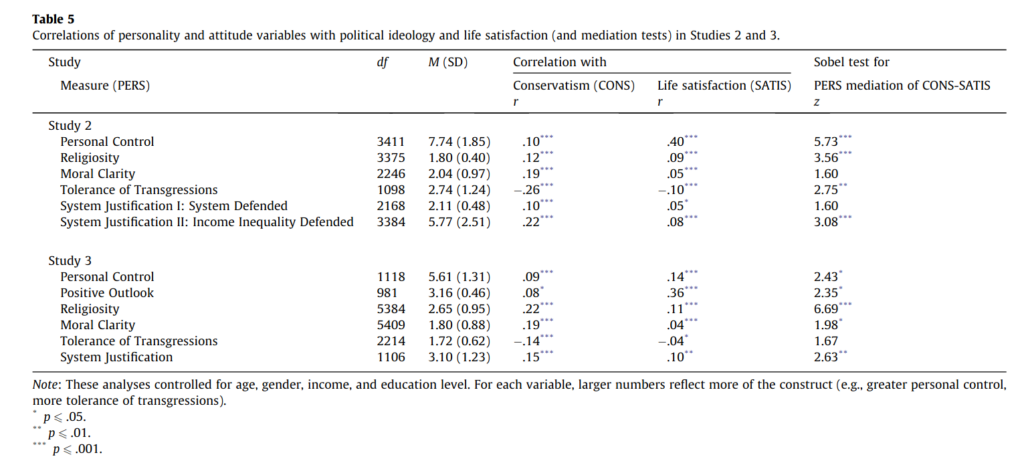

[In sample 2, the US adults in World Value Survey] First, conservatism was again related to life satisfaction overall (r = .13, p < .001, df = 3690), and after controlling for age, gender, income, and education level (r = .12, p < .001, df = 3411). Second, as shown in Table 5, conservatism was related to measures of personal control, religiosity, moral clarity, tolerance of transgressions, and system justification; and each of these variables was significantly related to life satisfaction. Third, personal control mediated the conservatism–satisfaction relationship, as did religiosity and tolerance of transgressions. Moral clarity (which focused on only one aspect of the broader concept of moral commitment and was on only a 3-point scale) was not significant. The system justification item about defending inequality was significant but the item about defending society was not. Thus, the relationships observed with our college student sample were largely replicated among a broader, more diverse sample of US respondents

And:

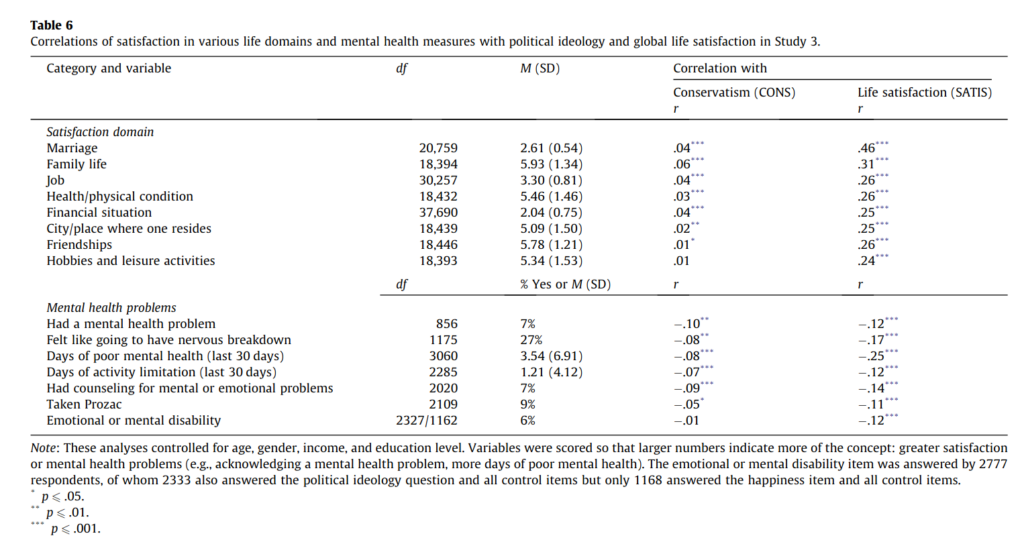

As shown in Table 6, conservatives reported better mental health than liberals on 6 of the 7 questions (the only exception asked about mental ‘‘disability,’’ a more severe problem that only 156 of 2777 respondents admitted having). Conservatives not only have personality and attitude qualities that are usually associated with positive adjustment and mental health, they also report being in better mental health, with fewer problems and bad mental health days.

Table 6 is here:

This is more or else what I also did and found. Their fourth sample is some reanalysis of the Jost paper, which we don’t care about too much here.

- Dobersek, U., Wy, G., Adkins, J., Altmeyer, S., Krout, K., Lavie, C. J., & Archer, E. (2021). Meat and mental health: a systematic review of meat abstention and depression, anxiety, and related phenomena. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 61(4), 622-635.

Objective: To examine the relation between the consumption or avoidance of meat and psychological health and well-being.

Methods: A systematic search of online databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, Medline, and Cochrane Library) was conducted for primary research examining psychological health in meat-consumers and meat-abstainers. Inclusion criteria were the provision of a clear distinction between meat-consumers and meat-abstainers, and data on factors related to psychological health. Studies examining meat consumption as a continuous or multi-level variable were excluded. Summary data were compiled, and qualitative analyses of methodologic rigor were conducted. The main outcome was the disparity in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and related conditions in meat-consumers versus meat-abstainers. Secondary outcomes included mood and self-harm behaviors.

Results: Eighteen studies met the inclusion/exclusion criteria; representing 160,257 participants (85,843 females and 73,232 males) with 149,559 meat-consumers and 8584 meat-abstainers (11 to 96 years) from multiple geographic regions. Analysis of methodologic rigor revealed that the studies ranged from low to severe risk of bias with high to very low confidence in results. Eleven of the 18 studies demonstrated that meat-abstention was associated with poorer psychological health, four studies were equivocal, and three showed that meat-abstainers had better outcomes. The most rigorous studies demonstrated that the prevalence or risk of depression and/or anxiety were significantly greater in participants who avoided meat consumption.

Conclusion: Studies examining the relation between the consumption or avoidance of meat and psychological health varied substantially in methodologic rigor, validity of interpretation, and confidence in results. The majority of studies, and especially the higher quality studies, showed that those who avoided meat consumption had significantly higher rates or risk of depression, anxiety, and/or self-harm behaviors. There was mixed evidence for temporal relations, but study designs and a lack of rigor precluded inferences of causal relations. Our study does not support meat avoidance as a strategy to benefit psychological health.

OK, not a study of politics, but related, and funny. Got a lot of attention, and was also openly funded by the meat industry, who is presumably annoyed by their crazy enemies.

The most common objection to my study was the reliance on medical diagnosis, as opposed to self-report symptom scales. Well, all these other studies basically used symptom scales, and they find the same thing. The only worry remaining is that there might be test bias, i.e., that lefties are more likely to self-report and acquire symptoms of issues because they are more open to them, and this would then lead to an inaccurately large difference. This requires a measurement invariance study, which has not been done as far as I can find. So that task remains, but really, how much do we think this likely accounts for? Almost all such ‘where is the measurement invariance study? If you don’t have it, I will presume your finding is spurious’ are examples of isolated demands for rigor, since these are almost only made to left-hostile findings, not the other way around (find me any study of measurement invariance of the higher openness, IQ etc. of left-wingers!).

So all in all, I think we can be confident this gap is real. The conservative advantage seems to be their more griller attitude, of accepting inequality as reasonable, and thus focusing their time on playing a game fair, achieving their goals within the system such as it is. The left-wing mentality is more about complaining that life is unfair. As a matter of fact, such books are very common, even by left-wing behavioral geneticists.