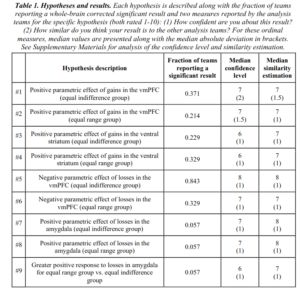

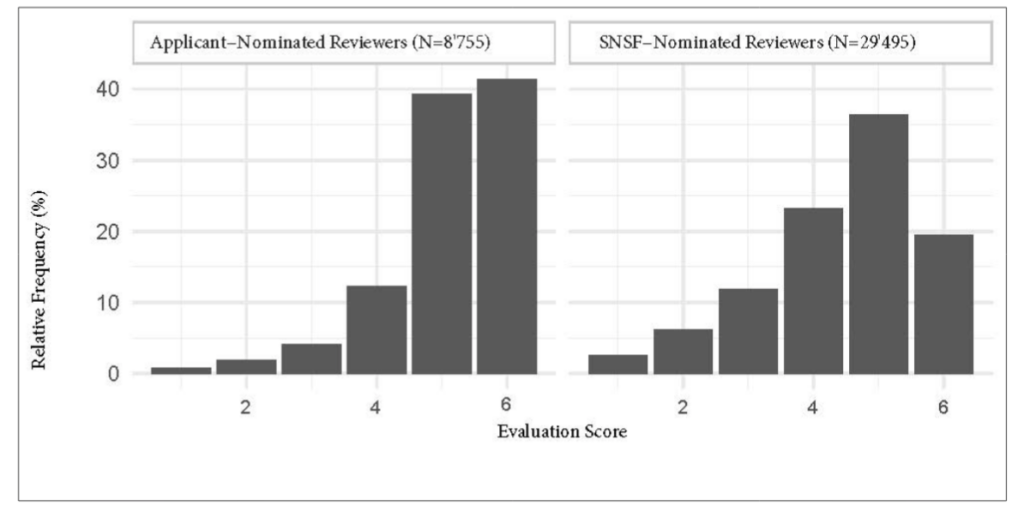

Leo Tiokhin has a post up arguing the opposite of the title of my post. His argument is that a number of studies find that reviewers suggested by authors provide more positive reviews. E.g. this study of Swiss grant reviewers:

He advocates a conflict of interest (nepotism) explanation for this:

If you’re thinking, “wait a second, aren’t the people who get to recommend reviewers the same people who benefit most from receiving positive reviews?” then you’re not alone.

Sure, and the reviewers might even benefit from some of the grants, giving them even more conflict of interest. Yet there is an alternative explanation, as he notes:

There is an alternative possibility for why applicant-nominated reviewers provide more positive reviews: applicant-nominated reviewers may be more familiar with a research area and be better able to determine whether the research is important or impactful.⁵

5. Severin and colleagues note this as a potential alternative explanation:

“Reviewers who were nominated by applicants via the “positive list’” on average tended to award higher evaluation scores than reviewers nominated by SNSF administrative offices, referees or other reviewers. This effect can be interpreted in several ways. First, applicant-nominated reviewers may award more favorable evaluation scores because they know the applicants personally and/or have received positive evaluations from the applicant in the past (Schroter, 2006). This would mean a conflict of interest. Second, applicants may nominate reviewers who are experts within their field and therefore might be particularly familiar with their research and will recognize the impact and importance of their grant application.”

6. A third possibility, suggested to me by Karthik Panchanathan, is that authors or grant applicants nominate reviewers who share their aesthetic preferences, such as preferring research that comes from a certain disciplinary perspective or uses particular methods.

Now we are getting somewhere. Science really works as a kind of system of loose schools of thought. Sometimes people study the same thing but with wildly different opinions and methods. There are several such schools in economics. Typically, one school will be the current dominant school. If you assigned reviewers at random, then, work by minority school members would have a hard time getting through peer review. That is because members of each school will be more inclined to accept work by their own members, and inclined to reject work by non-members. This process will then lead to exclusion of the minority schools from science. Since the history of science shows quite clearly that breakthroughs are sometimes, maybe often, done by mavericks or minority school members, then this situation would be very bad for progress. Try to think of an economist trying to do free market type research in the Soviet Union or China. He sends his work to a suitable journal (The ‘The Soviet Journal of Economics’). The editor duly follows the above advice and sends the paper to random experts, the economist professors in that country. Almost all of these experts will be members of the dominant communist economics school, and will reject the work (might even report the author to the NKVD/STASI). He will only get published if he happens to hit another heterodox researcher. Since these are rare, this will not happen often, and his work will generally be rejected many times. He might even quit science.

The above situation is extreme, but reality is not so far from it. Intelligence research has historically been deeply unpopular. Suppose you did intelligence research in 1970. You did a study showing that social inequality seems to be caused by intelligence, and that seems heritable, so social inequality must also be somewhat heritable. You then send this to a journal of sociology. If you were assigned random reviewers in that area — sociology professors — you will almost surely be rejected then and also now. Almost all sociology professors are left of center, a large proportion of which are communists. The situation in psychology is somewhat better, but your odds are still bad. What should intelligence researchers do? Well, they did what every field of research eventually does: they made their own journals, so that work by members of their school would be evaluated by other members of their school. This is why we have journals like Intelligence (founded by Douglas Detterman), Personality and Individual Differences (founded by Hans Eysenck), Mankind Quarterly, and yes, OpenPsych (founded by me and Davide Piffer). Economists do the same thing, so that’s why we have journals like Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Cambridge Journal of Economics (Marxist), and Cliodynamics (quantitative history).

I submit that there is a continuum between suggesting your own reviewers and having your own journals. This diversification of interests, methods, and goals are a necessary part of the scientific process. The purpose of peer review is to increase the quality of published work by denying publication to low quality work (‘reject’), and provide suggestions for improvement of work (‘revise and resubmit’). For many people, however, the rejection rate has become a sign of quality itself. The most popular journals have extreme rejection rates. From their perspective, the point of peer review is to maximize the rejection rate. But despite this, they don’t actually publish higher quality science as measured by objective methods, maybe even lower quality science. In contrast, by allowing authors to suggest reviewers, peer review’s gatekeeping function is less extreme. It is now asking authors: can you point us to 2-3 experts in this area who agree your work is worthy? If so, we grant you publication. This approach allows authors of heterodox work to still get it published as long as they can convince a few fellow experts.

The above is a simplified model of scientific publishing, of course (feature not a bug). However, there is evidence of this kind of thing from actual reviews and citation network distances. My favorite study on this topic is this one:

- Teplitskiy, M., Acuna, D., Elamrani-Raoult, A., Körding, K., & Evans, J. (2018). The sociology of scientific validity: How professional networks shape judgement in peer review. Research Policy, 47(9), 1825-1841.

Professional connections between the creators and evaluators of scientific work are ubiquitous, and the possibility of bias ever-present. Although connections have been shown to bias predictions of uncertain future performance, it is unknown whether such biases occur in the more concrete task of assessing scientific validity for completed works, and if so, how. This study presents evidence that connections between authors and reviewers of neuroscience manuscripts are associated with biased judgments and explores the mechanisms driving that effect. Using reviews from 7981 neuroscience manuscripts submitted to the journal PLOS ONE, which instructs reviewers to evaluate manuscripts on scientific validity alone, we find that reviewers favored authors close in the co-authorship network by ∼0.11 points on a 1.0–4.0 scale for each step of proximity. PLOS ONE’s validity-focused review and the substantial favoritism shown by distant vs. very distant reviewers, both of whom should have little to gain from nepotism, point to the central role of substantive disagreements between scientists in different professional networks (“schools of thought”). These results suggest that removing bias from peer review cannot be accomplished simply by recusing closely connected reviewers, and highlight the value of recruiting reviewers embedded in diverse professional networks.

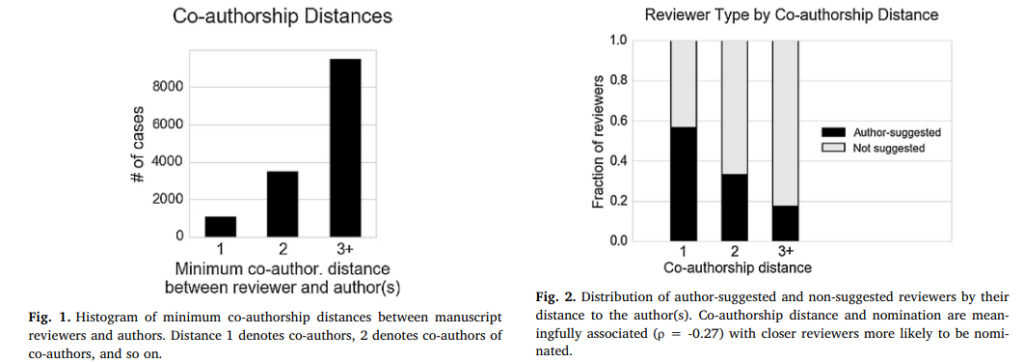

Let’s look at their results. First, the distribution of reviewers by distance:

Almost all reviewers are not coauthors (distance 1), so already we see that PLOS ONE follows mostly the ‘maximize rejection rate’ policy. Interesting is also that authors actually suggest quite a number of non-coauthors as reviewers. In fact, they may even engage in strategic non-collaboration, so that they can serve as each other’s peer reviewers. I do that, so others probably do that too.

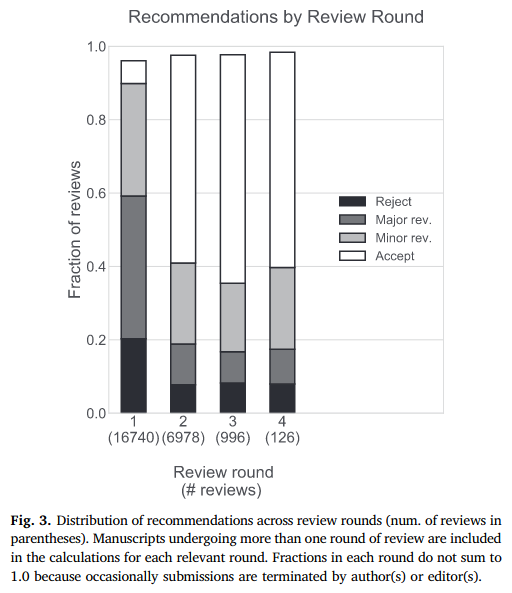

Reviewer usually occurs in rounds. Since reviewers don’t generally agree much more than chance levels, then the first round is almost never accept (for which you need 2-3 people to randomly agree to take your work as is). And one can even get rejected after multiple rounds of reviewing, wasting everybody’s time:

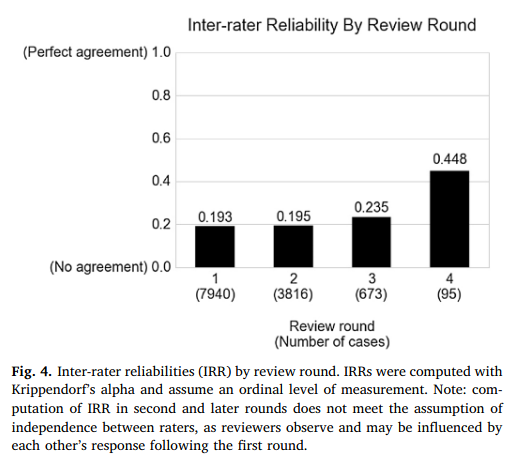

Another way of looking at the above is to look at reviewer agreement by round, which increases:

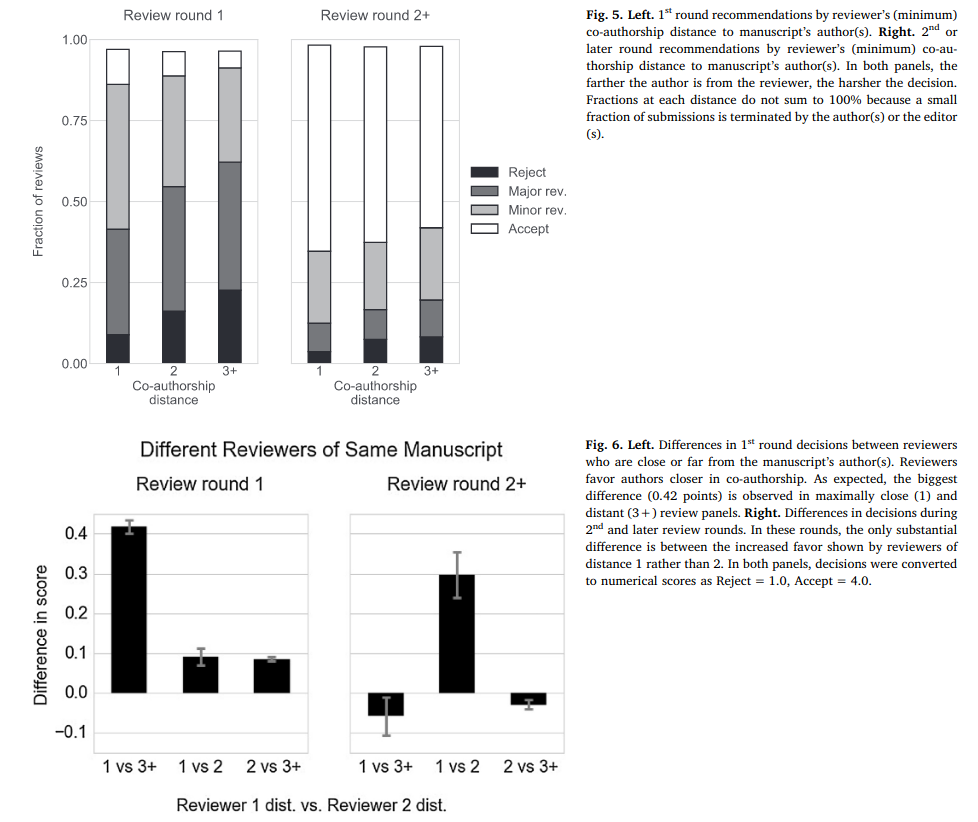

Finally, the main results of looking at the effect of co-authoring distance on review decision:

We see that the closer reviewers are to the authors in authoring network, the more positive they are. This is true also for the distinction between 2nd (coauthors of coauthors) and 3rd+ degree coauthors. It is a shame they didn’t try to distinguish further out. I asked Teplitskiy about this and he said this was a technical limitation: “We had limited access to Scopus, and could only access it via a slow API. So instead of querying all co-authorship relations and constructing full network, we could only query, for a particular person (“seed node”), the list of their coauthors identities. We used all authors/reviewers/editors in our PLOS dataset as seed nodes.”.

The 2nd degree coauthors are generally pretty distant, I have about 45 1st degree coauthors, and several hundred 2nd degree coauthors, most of which I don’t know. As a matter of fact, with the stark increase in number of authors on papers, quite a large proportion of 1st degree coauthors will be unknown. I have several I don’t know, as they came from a collaboration I joined. The number of 3rd degree coauthors must be in the thousands, almost all of which are unknown. Still, the nepotism models says that close authors can potentially gain from helping each other out in a small network. However, 2nd order coauthors probably are too distant to know each other in most cases, so they don’t generally have nepotistic motives. They do however have substantial chance of working in the same school of thought (e.g. another intelligence researchers, or Keynesian economist), so they will be inclined to view work by fellow members positively. The 3rd+ degree people are essentially random people in the same broader area.

Authors themselves conclude:

Our analysis of review files for neuroscience manuscripts submitted to PLOS ONE show that reviewers disagreed with each other just as often as reviewers in conventional review settings (inter-rater reliability = 0.19) that value subjective criteria, such as novelty and significance. Furthermore, we found the same pattern of favoritism: reviewers gave authors a bonus of 0.11 points (4-point scale) for every increased step of co-authorship network proximity. It bears emphasis that we observe these levels of disagreement and favoritism in a setting where reviewers are instructed to assess completed manuscripts on scientific correctness alone.

Such patterns of disagreement and favoritism are difficult to align with a view of the research frontier as unified by a common scientific method and divided only by distinctive tastes for novelty and significance. These patterns are instead consistent with scholarship on “schools of thought.” According to this view, the highly uncertain parts of the research frontier are explored by competing clusters of researchers, members of which disagree on what methods produce valid claims and what assumptions are acceptable. As one editor put it, “there is a little bit of groupthink going on, where if it’s someone in my circle, we’re on the same wavelength, and I may even be subconsciously predisposed to like it.” The patterns we find are also consistent with nepotism–reviewers’ strategic aims may corrupt even straightforward assessments of validity. Nevertheless, we presented several factors that strongly suggest schools of thought play a major, if not primary role. First, incentives to review strategically are likely to be much lower in the modest-impact and non-zero sum setting of PLOS ONE. Second, policies designed to reduce bias directly, such as blinding reviewers from observing authors’ identities, have proven notably inconsistent in identifying even small effects (Jefferson et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2013). Lastly, as discussed in section 4.5, even distant reviewers, who we expect to be non-nepotistic, give more favorable scores than very distant reviewers, who we expect to be equally non-nepotistic. Although not conclusive, we believe this study provides the strongest available quantitative evidence for the impact of schools of thought on evaluation of scientific ideas.

So in general, I think we should be quite vary about implementing policies that in practice try to maximize the rejection rate by removing all possibility of nepotism. This will also affect minority schools of thought and just in general heterodox researchers. The history of science shows that these people are very important for progress. I agree that some safeguards against nepotism are sensible. For instance, I would guess that journal editors typically do not use more than 1 author suggested reviewer. At OpenPsych, the editors avoid picking close coauthors for reviewers: people who have recently worked together, or did a lot of work together. The role of editors in determining the fate of submissions is generally not studied much, as journals don’t want to share this information, potentially opening them to criticism about nepotism. So we continue with peer review as a kind of biased black box. One of the goals of OpenPsych was to push the open science reform in the differential psychology area by opening up all the reviews, and the identities. So far I think it has worked out fairly well, and other journals are adopting similar policies.