So it was finally published, our reply to our frenemies Eric Turkheimer and his student Evan J. Giangrande. For good measure, it’s these two guys:

The saga begins in 2020:

-

Pesta, B. J., Kirkegaard, E. O., te Nijenhuis, J., Lasker, J., & Fuerst, J. G. (2020). Racial and ethnic group differences in the heritability of intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intelligence, 78, 101408.

- Giangrande, E. J., & Turkheimer, E. (2022). Race, ethnicity, and the Scarr-Rowe hypothesis: a cautionary example of fringe science entering the mainstream. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(3), 696-710.

- Pesta, B. J., te Nijenhuis, J., Lasker, J., Kirkegaard, E. O. W., & Fuerst, J. G. R. (2023). On group differences in the heritability of intelligence: A reply to Giangrande and Turkheimer (2022). Intelligence, 98, 101737.

Really though, it begins in 1969 with Arthur Jensen who examines race differences in learning ability, intelligence scores, school outcomes in his famous 1969 article. It is eminently readable here 50+ years later, and still mostly accurate. This is not a bad thing. It shows the stability of central findings in differential psychology, behavioral genetics, and race science. Two years later, Sandra Scarr advocated a possible model:

- Scarr-Salapatek, S. (1971). Race, Social Class, and IQ: Population differences in heritability of IQ scores were found for racial and social class groups. Science, 174(4016), 1285-1295.

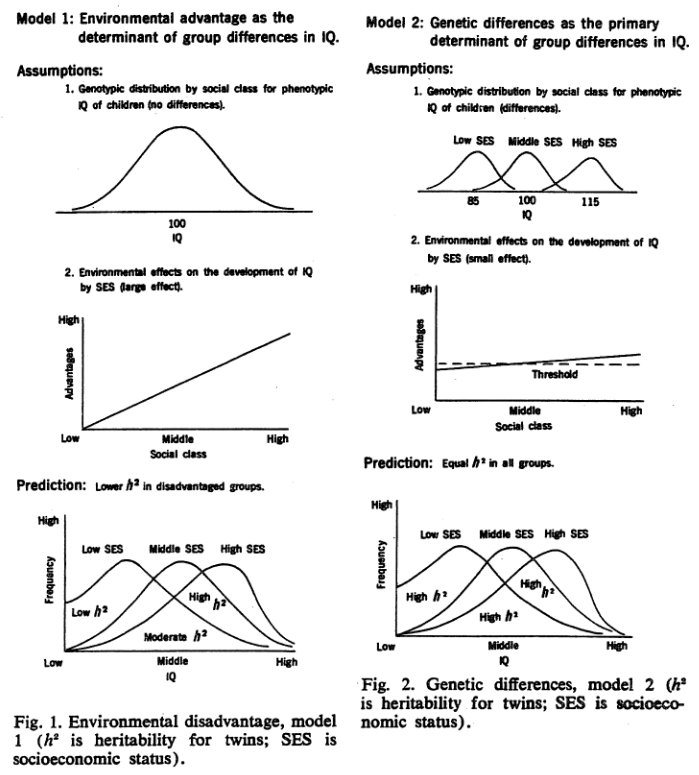

Her model is that the level of social status (wealth, education, social class) of parents should modify the heritability estimates:

The idea is that when societies are not well developed, there is a lot more environmental variation with regards to the development of intelligence. Because heritability of the proportion of a phenotype (anything you can measure about a person) variance that is due to genetic variance, heritability should be lower for countries or times with more such relevantly varying environments. And the same is true for social class groups or races within a given society. We might also posit a threshold effect such that beyond a certain level of, say, family income, more income isn’t able to improve intelligence any further. Think of a family that is on the drink of starvation in the early 1900s. Their kinds are stunted, they don’t attend more than 3rd grade school, never properly learn to read and write because they have to help the family on the farm, and their food isn’t the best either — mostly variations on maize and potatoes. This is not the best environment for the development of intelligence. Then we can imagine a comfortable middle class family from 1950. They have clean water, the dad has a decent job, the mother works at home taking care of the family and the house. They don’t eat the most expensive food, but it is decently varied, and they have access to public libraries in the school and elsewhere, and can buy any other books within reason. This environment sounds a lot better for the development of intelligence. Now imagine a modern family. They have everything in far greater quantities than the 1950s family, computers, any kind of food, nutritional advice, modern medicine, vaccines against childhood diseases, the internet, long schooling etc. Thinking of the rearing environments the children in these families grow up in, it is reasonable to suppose that the improvement from the first to the second family matters more than the improvement from the second to the third. Or from the third to an even richer family, say, being the child of Bill Gates or Elon Musk.

We can probably intuitively accept that there are diminishing returns to improving the rearing environment, but where does the diminishing returns set in? In the above model, Scarr considered a simple threshold function, which is less realistic but easier to consider mathematically. The implication of this line of thinking is that heritabilities should be higher in higher SES families. And that’s where race comes in. Scarr was writing about the American situation and in that country and pretty much everywhere else, African-descent (“Blacks”) people have lower SES, so their children are exposed to worse environments, potentially stunting some part of their cognitive abilities. Scarr’s 1971 study is the first attempt at tying together all these ideas with a quantitative analysis. Later another researcher David Rowe also studied this, and they together got their names on this idea: the Scarr-Rowe effect. Later authors like James Flynn (1980) also argued along similar lines against Jensen’s views.

But really, it wasn’t actually Scarr’s idea. In fact, this whole line of argument was Jensen’s own idea (1968)! Giving his best ideas to his critics was typical Jensen:

One way of testing the hypothesis that a particular segment of the population is intellectually handicapped because.of its position on the environmental continuum would be to carryout a heritability study within this segment of the population. If the hypothesis represented by Figure 2 has any merit, heritability estimates should be significantly lower for groups reared in the more disadvantaged part of the environmental continuum. Here, then, is one feasible means of directly testing the hypothesis that Negroes perform below most other groups on tests of intelligence and scholastic achievement because of environmental rather than genetic difference.

So who is right? Are Blacks’ heritability for intelligence lower than Whites’ in the USA or not? Or are American Blacks already far beyond into the diminishing returns part of the curve where we can’t see any differences? Our study was the first meta-analysis of this claim:

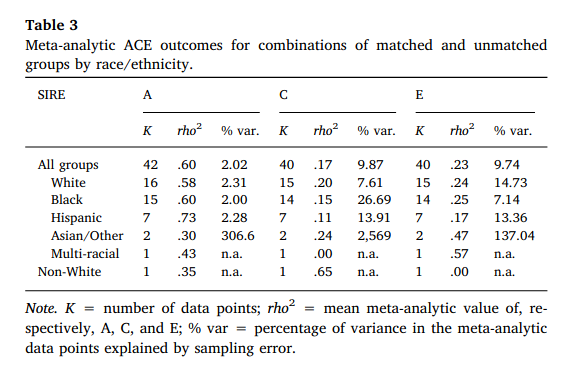

Via meta-analysis, we examined whether the heritability of intelligence varies across racial or ethnic groups. Specifically, we tested a hypothesis predicting an interaction whereby those racial and ethnic groups living in relatively disadvantaged environments display lower heritability and higher environmentality. The reasoning behind this prediction is that people (or groups of people) raised in poor environments may not be able to realize their full genetic potentials. Our sample (k = 16) comprised 84,897 Whites, 37,160 Blacks, and 17,678 Hispanics residing in the United States. We found that White, Black, and Hispanic heritabilities were consistently moderate to high, and that these heritabilities did not differ across groups. At least in the United States, Race/Ethnicity × Heritability interactions likely do not exist.

In a table:

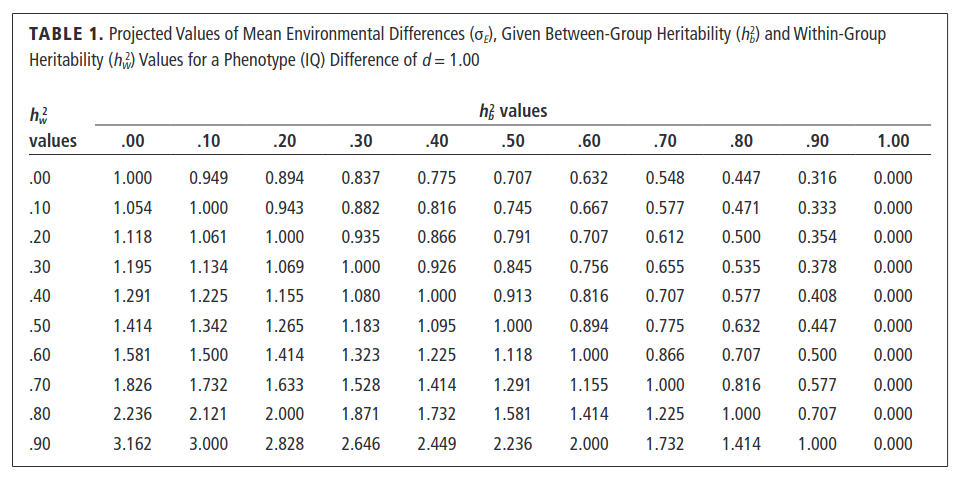

We found that for Blacks and Whites, there’s no difference. The estimates were 58% for Whites and 60% for Blacks. Hispanic was estimated at 73% but with much less data, so it should not considered a real difference. This finding is very problematic for those claiming no genetic contribution to the Black-White gap because equal and high heritabilities for intelligence makes their case untenable. Why? Jensen’s variance argument. Russell Warne (2021) provides a modern summary, but the short-form is this: If we assume that there are no differences in the average genetic intelligence between two groups (Black and White, but it could be any), then the entire group difference must be due to non-genetic, that is, environmental effects. However, if we know that within-groups, variation in intelligence is mostly caused by variation in genetics, and less so environmental factors, it potentially makes the math impossible. If we accept a 80% heritability for adult intelligence (and we should), that means that there is only 20% variation left that could cause the gap. As variance is a squared metric, to get the causal effect size, we take the square root, so we get sqrt(0.20) = 0.45 beta. Now, if we know that the groups differ by 1 standard deviation (15 IQ), we can see that this hypothetical environmental cause must be 1/0.45 = 2.24 standard deviations higher for the Black group. However, looking around at datasets, there are no environmental differences for Blacks and Whites in America that are this big, not even when combined. Recall, that combining them is sub-additive because people with lower incomes also have lower educational attainment, lower social class, live in worse neighborhoods etc., on average. We can also construct a table for different sets of numerical assumptions, here from Warne’s article:

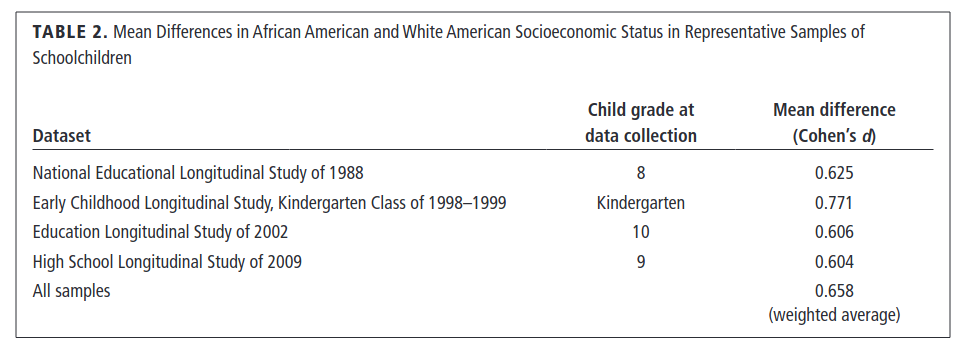

On the far left is the assumed within-group heritability for both groups. If we assume this is 80%, and the between-group heritability is 0 (h²b, in second column), then the gap size of the non-genetic cause must be 2.24 d, same value as above. You can pick any other values you prefer. If you think 80% is too high, you can look at 60% and see that the gap size must still be 1.58 d, impossibly high. For the record, here are some observed gap sizes for family SES from Warne’s paper:

So, the overall gap size for these kinds of family measures is about 0.66, far far too low for the required values. In fact, you could try to go backwards: if the gap we see is about 0.66, which values of the model make sense? The between-group heritability must be at least 50% to get a fitting value, but that’s assuming an absurd within group heritability of 0%. If we won’t go lower than 60% heritability within-group, then the between group heritability must be between 80% and 90%!

There aren’t that many great options for those who claim the between-group heritability is 0. They can 1) claim heritabilities are actually much lower for Blacks and Whites, or 2) claim heritabilities are lower for Blacks only, or 3) claim some kind of magical cause of gaps that has no within-group variation. Decades of attacks on heritability estimates has generally failed to lower the estimates, so option (1) has been more or less exhausted. Option (2) is the promise of Scarr-Rowe effects if real, and that’s why Sandra Scarr pursued them. Option (3) is nonsensical as there is no such cause in real life that doesn’t vary between families but somehow varies between racial groups. (For those psychometrically inclined, this model is also ruled out by strict measurement invariance.) This leaves environmentalists mainly with (2). Our paper was a new examination of this escape route from Jensen’s variance argument. As we failed to find any difference, the evidence is now also strongly against this option, which leaves no more options.

QED? Well, not according to Turkheimer and Giangrande, who teamed up with his student and gathered an even larger dataset to show that there really are such differences in heritability and we are scientifically mistaken wrote a weird polemic attack on our paper in a different journal. You get the idea from the title of their paper “Race, ethnicity, and the Scarr-Rowe hypothesis: a cautionary example of fringe science entering the mainstream“. So, rather than attack us on scientific grounds, it mostly consists of trying to misdirect the debate. Truly bizarrely, the main claim of G&T (their initials) is that… Scarr-Rowe was never really about race at all! So we had to again review this history lesson, which Turkheimer surely knows, as he himself cited these papers at various points. In our words:

In sum, our literature review demonstrates that Jensen, Osborne, Vandenberg, Nichols, Scarr, Hodges, Rowe, Guo, and even Turkheimer himself, were interested in race/ethnicity x heritability interactions (either in-and-of themselves or via SES). Contrast this with G&T, who instead suggested that Pesta et al. “create[d] the false impression that their race- and ethnicity-based analyses are founded on well-established literature” (p. 4).

The rest of G&T proceeds in similar fashion, e.g.:

G&T also claimed that race x heritability interactions have no bearing on interpreting SES x heritability interactions. This statement is in direct contrast with statements made by Rhemtulla and Tucker-Drob (2012), who worried that SES x heritability interactions might be confounded by race x heritability interactions. Therefore, it is obviously important for modern researchers to test whether SES x heritability interactions are indeed independent of race x heritability interactions. This is not new in the literature, as Scarr-Salapatek (1971a), Turkheimer et al. (2003), as noted by Turkheimer (personal communication, October 4th, 2013), and others have conducted these tests. Also, as discussed above, Pesta et al. (2020) fully acknowledged that certain racial/ethnic groups may be environmentally disadvantaged in biological (e.g., in terms of nutrition, lead exposure, or iodine deficiency) or social ways not captured by SES.

They complain about various strange things. For instance, since not many papers reported ACE (twin study) estimates by race, often we carried out new studies using public datasets, or wrote authors to ask them to compute results for our meta-analysis. Honestly, we would normally be commended for being thorough and avoiding potential publication bias, but G&T scolds us for doing new analyses ourselves instead! G&T also complains about our weighting scheme (correctly!), but ignores that in our original article we also reported results using another scheme, and these were about the same — weights don’t affect these results much. And on and on it goes.

Academic politics

The next part was trying to publish our reply. The idealistic view of science is that you publish some study, someone else publishes criticism, you publish a reply to the criticism, and on and on until the marketplace of ideas has figured out who is right. So first we tried the journal where G&T published their paper, but got rejected twice. We chronicle this timeline in our appendix for those who are very interested in that drama. So eventually we gave up and sent it to Intelligence, the journal that initially published our work. This kind of thing is quite typical. Editors don’t want a potentially hot potato in their journal, so they look around for whatever reason or policy can be given. If no one ever talks about this problem, no one will do anything about it. But talking about it can be construed as whiny. Indeed, Kevin Bird AKA Commie Kevin did just this thing on Twitter to mock our new paper:

Here it should be noted that Kevin Bird is playing a two-faced game. He and his communist friends send emails to journals to complain about our work, to their universities, and succeeded in getting Bryan Pesta fired, and potentially was part of other people getting fired. Then he mocks us publicly for complaining about mistreatment. What kind of person does that? Well, here’s some of his other tweets:

Make your own judgments about his character.

Drama aside, it seems we have closed one of the remaining escape paths in the race and intelligence debate. A lot of other work remains, for instance, more analyses using polygenic scores of both modern and ancient genomes. You can subscribe to this blog to further this research.