In moral philosophy, there is a theory of morality which is nearly universally used as a wrong-headed theory. It’s the might makes right theory. In other words, whoever is in power decides what is right, like for real. Textbooks will then ask the reader whether it was really morally correct in Nazi Germany to orchestrate genocide and subjugate the neighbors, whether it was right in Soviet Russia to gulag dissidents and starve the Ukrainians, whether it was right in communist Cambodia to kill all people with glasses etc. The intention of this is to make the reader go like “no way”, thus showing that morality is something that transcends a given time or place (objective morality). Of course, some other people use it as a kind of cynical, Machiavellian descriptive morality, as in, the powers that be determine what laws and norms are good and which are bad, no matter if they are really good or bad in some deeper sense.

However, what humans consider moral is a function of evolution, a fact that causes a lot of problems for any strong metaphysical views of morality (especially natural law theory, upon which the human rights doctrine depends and the American constitution). One popular theory of moral realism is that of the ideal observer theory. That’s the theory that e.g. David Hume is often taken to be a proponent of:

Hume uses this human experience to explain moral judgement. For Hume, the statement “X is good.” means the same as the statement “X is such that it would elicit the “moral approval” of all or most normal, sensitive, informed and unbiased people.” Similarly, “X is bad.” means roughly “X would illicit the moral disapproval of all or most normal, sensitive, informed and unbiased people.”

Applied to the real world, the view faces problems of universality. While there is such a thing as human nature, as in shared universals (pair bonding, fear of snakes, sexual division of labor etc.), there are also real differences in morality between populations. These probably have a partially genetic basis, making any talk about a sort of “one human” shared morality somewhat of an approximation. For instance, in a study of people’s responses to moral dilemmas, Awad et al 2018 found that:

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence have come concerns about how machines will make moral decisions, and the major challenge of quantifying societal expectations about the ethical principles that should guide machine behaviour. To address this challenge, we deployed the Moral Machine, an online experimental platform designed to explore the moral dilemmas faced by autonomous vehicles. This platform gathered 40 million decisions in ten languages from millions of people in 233 countries and territories. Here we describe the results of this experiment. First, we summarize global moral preferences. Second, we document individual variations in preferences, based on respondents’ demographics. Third, we report cross-cultural ethical variation, and uncover three major clusters of countries. Fourth, we show that these differences correlate with modern institutions and deep cultural traits. We discuss how these preferences can contribute to developing global, socially acceptable principles for machine ethics. All data used in this article are publicly available.

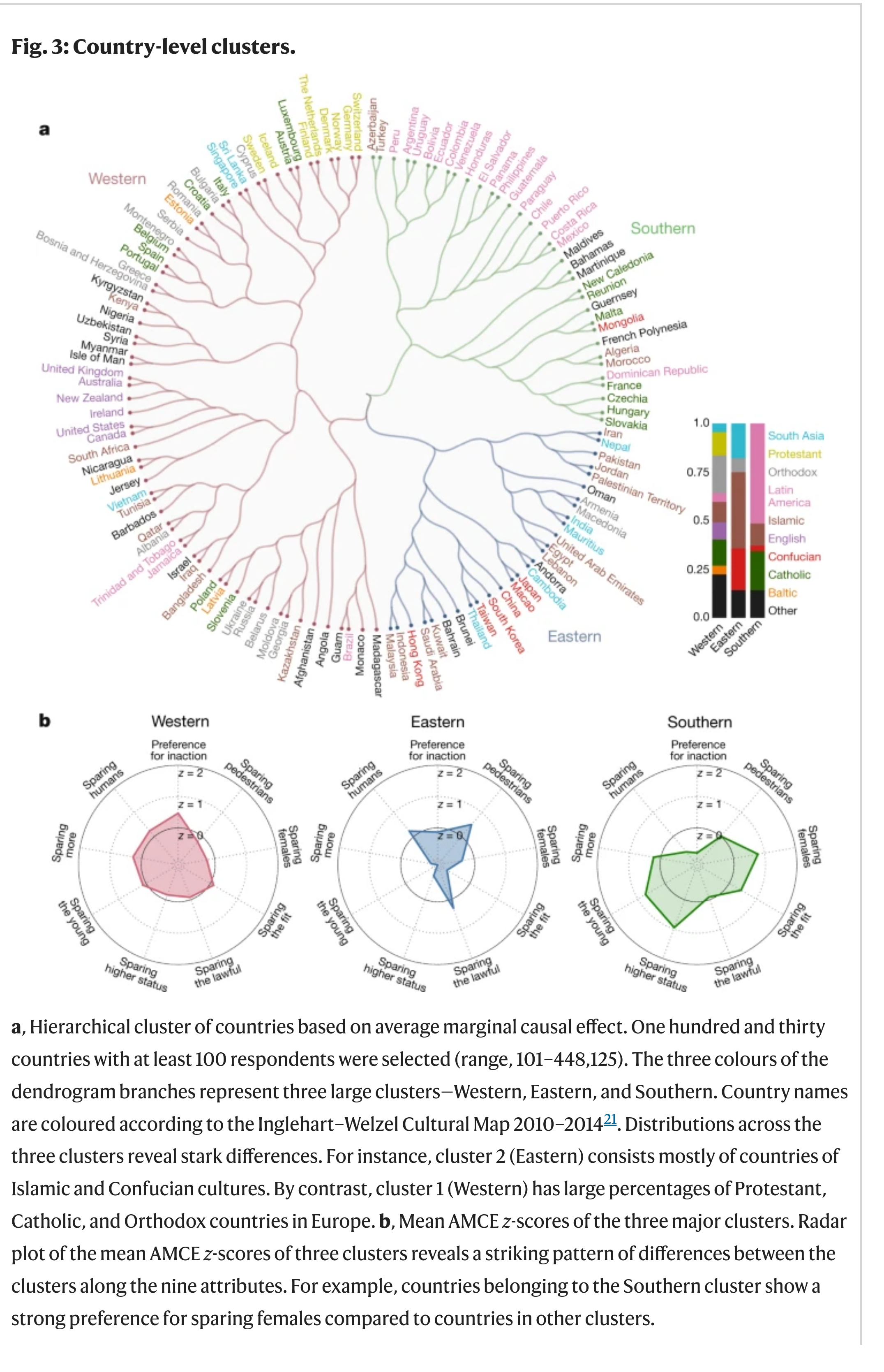

Visually:

They tried various ways of grouping countries by similar moral responding, and found a three-way split between Western, Southern, and Eastern. The split isn’t always sensible — why is Andorra grouped with Cambodia? — but it has some level of consistency (Japan, Macao, Taiwan, China, South Korea are all together, not a coincidence). Whatever the exact structuring of moral thinking across countries, cultures, and races, there is some variation that likely has a genetic basis. As such, people have evolved to have different moralities, so there cannot be just one human shared morality, but rather a variety of them. This isn’t too surprising if we consider various differences in moral behavior of people living in Western countries, say, on sociosexuality (sexual morals), life history speed (mate indiscriminately vs. long term partners only).

But it gets more tricky. In human history there was a lot of conquest. Some peoples got genocided by invading groups, say, the Neanderthals by homo sapiens. Their only remnant is a small part of Eurasians’ genomes (2-4%). Replacements sometimes happened by force (e.g. indo-Europeans), other times by migration of superior numbers (e.g. Anatolian farmers), and usually by some mix of these. But when this involves using violence, we will get back to the might makes right theory. As the replaced peoples no longer exist and the new inhabitants have the morality of the conquerors, morality according to the ideal observer will also be that of the conquerors. In that way, then, might does make right, if only in the long run. If one group of people replaced everybody else on Earth, their version of human morality would be the only human morality, and thus the truth, according to ideal observer theory.

I don’t know if anyone thought of this implication of this theory, but I’ve been pondering it the last couple of weeks.