Psychology is a popular field, so there’s quite a big market for introductory textbooks. I occasionally read these just to see how authors are introducing and treating various topics. In this case I read the recent book Psych (2023) by Paul Bloom. He’s somewhat edgy, having written books like Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (2016). The contents are:

Foundations

1. “Brain Makes Thought”

2. Consciousness

3. Freud and the Unconscious

4. The Skinnerian Revolution

Thinking

5. Piaget’s Project

6. The Ape That Speaks

7. The World in Your Head

8. The Rational Animal

Appetites

9. Hearts and Minds

Relations

10. A Brief Note on a Crisis

11. Social Butterflies

12. Is Everyone a Little Bit Racist?

Differences

13. Uniquely You

14. Suffering Minds

15. The Good Life

This looks fairly reasonable. Psychology is a big topic, and any book that tries to introduce the topic in 450 pages must be quite wide-ranging but brief.

As usual, block quotes from the book unless otherwise indicated, and my comments are in regular font.

I want to end this prologue with a note of humility. We know so much about the physical world and so little about mental life. This isn’t because physicists are smart and psychologists are stupid. It’s because my chosen domain of study is so much harder than Barrow’s. The mysteries of space and time turn out to be easier for our minds to grasp than those of consciousness and choice. In the pages that follow, I’ll be honest about the limitations of our young science and critical of some colleagues who think we’ve solved it all.

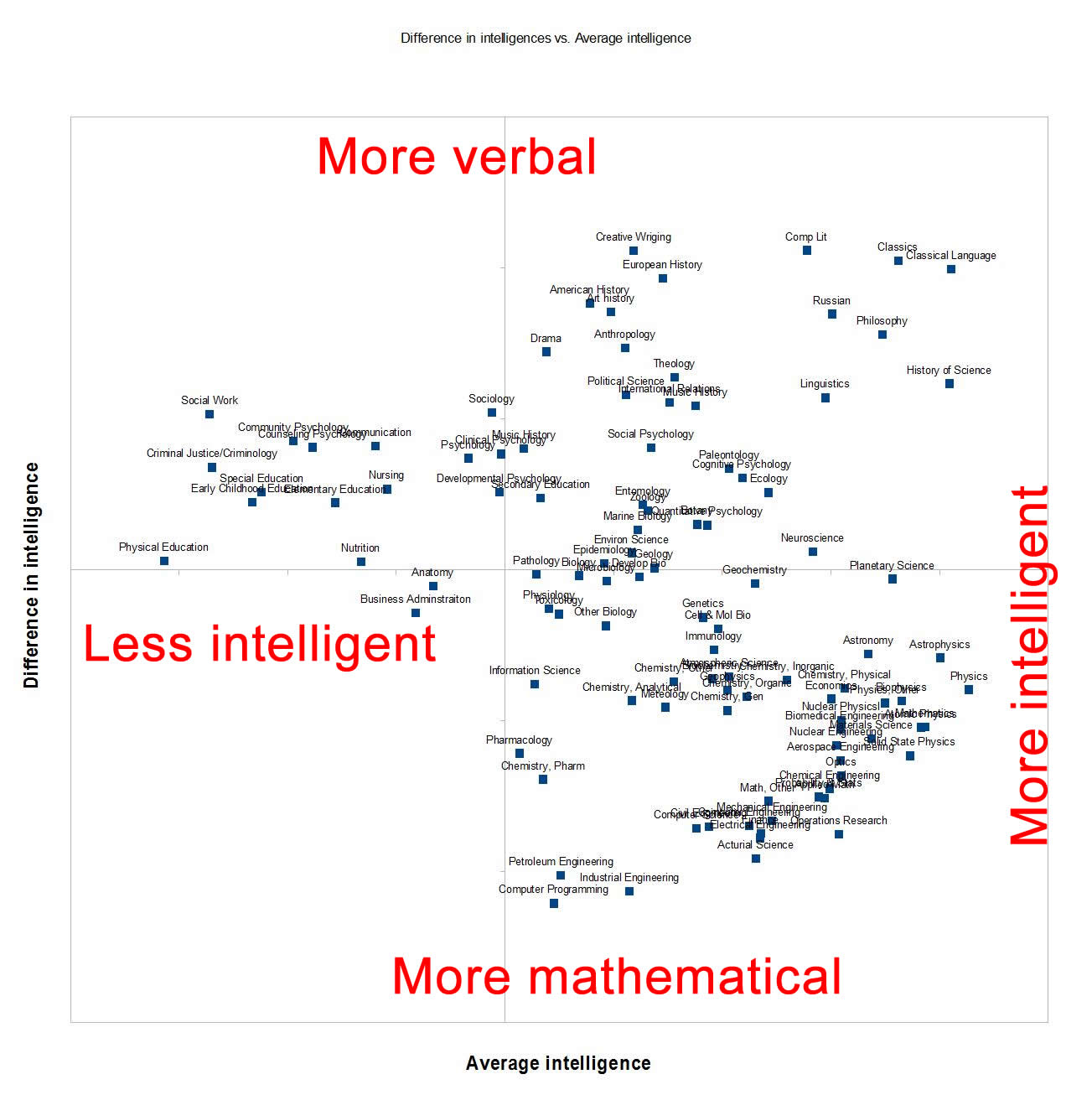

Off to a bad start! I wish psychologists would pay more attention to the study of psychologists. They are definitely not the smartest bunch, as can be seen in the endless replication failures in their field of research and the extreme fashion/fads of topics. But aside from casual observations, there’s of course quite a bit of data on which university degrees have more smarts. Here’s a typical set of results:

These are GRE (a standardized test) means by field, so these would be people applying to master and PHD degrees. These particular results are from Razib Khan’s old blogpost, but you can easily find newer and older versions of the same.

That being said, it is also true that psychology is inherently more complicated than physics. Particles don’t have ideas, they don’t change their behaviors in response to treatment, human subjects are hard to work with etc. But it’s not so clear whether psychology isn’t making so much progress because of the inherent difficulty of the field, or rather because it is done by people whose intelligence level just isn’t high enough to do science well. Certainly, some areas of psychology are doing very well. There’s no replication crisis in intelligence research. Behavioral genetics also fares fairly well, despite the usual egalitarian biases to support unlikely claims (e.g. gene-environment interactions).

Okay, then, what is the physical seat of thought? What is the source of our emotions, decision making, our passions, our pains, and everything else? Even a dualist must address some version of the question; the soul must connect to some part of our physical being to make the body act and receive its sensory information. (Descartes believed the conduit to be the pineal gland.)

For most of history, people thought that the answer was the heart. This was apparently the belief of diverse populations around the world, including the Maya, the Aztecs, the Inuit, the Hopi, the Jews, the Egyptians, the Indians, and the Chinese. It is a view at the foundation of Western philosophy; Aristotle wrote, “And of course, the brain is not responsible for any of the sensations at all. The correct view [is] that the seat and source of sensation is the region of the heart. . . . The motions of pleasure and pain, and generally all sensation plainly have their source in the heart.” After all, the heart responds to feelings; it pounds when you are lustful or angry; it is still when you are calm.16

It’s curious that this idea was so widespread despite it’s inherent implausibility. Even the ancient Greeks could see that animals differ in brain sizes, and that the ones with larger brains relative to body size were much smarter and had more complex behaviors. But then again, it is easy to be smart in hindsight. Aristotle wasn’t stupid, but he had some rather strange failings when it comes to biology. For instance, he wrote:

Males have more teeth than females in the case of men, sheep, goats, and swine; in the case of other animals observations have not yet been made: but the more teeth they have the more long-lived are they, as a rule, while those are short-lived in proportion that have teeth fewer in number and thinly set.

In light of modern knowledge, this is am odd failing. Surely, going to a school and counting the teeth of the children can’t have been that hard, or even a sample of adults.

Other creatures with brains have similar capacities for feelings and for rational action. A chimpanzee might shake with fear or bellow with rage. A cheetah chasing an antelope who darts behind a tree won’t run into the tree but will move around it. How do brains do all this?

People often get caught up in the seemingly paradoxical nature of this inquiry—isn’t it weird that we’re using our brains to understand our brains? One physicist, Emerson M. Pugh, wrote, “If the human brain were so simple that we could understand it, we would be so simple that we couldn’t.” The comedian Emo Phillips says, “I used to think that the brain was the most wonderful organ in my body. Then I realized who was telling me this.”

I think this is spot on. The brain is a neutral network. These are inherently complicated. It takes a more complicated neural network to understand a neural network (i.e., to back-engineer it). Humans aren’t smart enough to understand human neurology in detail, only AI could figure this out. But if/when it does, it won’t be able to explain this to us humans anyway. The good news is that complex models like neural networks can usually be summarized fairly well by the simpler models we can use, linear models and their extensions.

But sometimes people get too interested in the brain, neglecting the mind. Occasionally you bump into a neuroscientist who says that theirs is the real science. Sure, you can talk about ideas, emotions, short-term memory, and so on, but when you really get down to it, the serious theories will be about brain areas, neurons, and neurotransmitters. This is what matters. Neuroscience makes psychology irrelevant.

This attack on psychology is based on a confusion about how scientific explanation works. Just because we know about molecular biology doesn’t mean that we stopped talking about hearts, kidneys, respiration, and the like. The sciences of anatomy and physiology did not disappear. Cars are made of atoms but understanding how a car works requires appealing to higher-level structures such as engines, transmissions, and brakes, which is why physics will never replace auto mechanics. Or to take an analogy closer to psychology, you can best understand the strategies that a computer uses to play chess by looking at the program it implements, not the material stuff the computer is made of. The same chess program can run on a 1980s mainframe computer, a 1990s desktop, a 2000 laptop, or a present-day smartphone. The physical structure of the hardware changes with each generation, but the program can stay constant.

The true test of a science is whether it can predict the future. While it is true that psychology is reducible in theory to neuroscience, in practice it would be stupid to try to make predictions about humans based only on neuroscientific models. We don’t make predictions of animal evolution based on molecular biology either.

There are studies in which psychologists tell people stories about somebody who has a meal in a restaurant, and later ask their subjects what they remember about the story. People add plausible details. Someone might remember that they’ve been told the diner paid the bill even if it wasn’t in the story, just because this is what people do in restaurants.44 Just as with the similar phenomenon in perception, this sort of “filling in” is a rational way for the mind to work.

Another example of this is from a classic paper published in 1989, called “Becoming Famous Overnight.”45 The first paragraph summarizes the findings, and it’s so well written (at a level that I have very rarely seen in a scientific journal) that I’m going to quote it here:

Is Sebastian Weisdorf famous? To our knowledge he is not, but we have found a way to make him famous. Subjects read a list of names, including Sebastian Weisdorf, that they were told were nonfamous. Immediately after reading that list, people could respond with certainty that Sebastian Weisdorf was not famous because they could easily recollect that his name was among those they had read. However, when there was a 24-hr delay between reading the list of nonfamous names and making fame judgments, the name Sebastian Weisdorf and other nonfamous names from the list were more likely to be mistakenly judged as famous than they would have been had they not been read earlier. The names became famous overnight.

We see this sort of misattribution all the time in the real world. I once told a story to friends about a funny but somewhat stressful experience I had a few years ago, and later on, my wife gently reminded me that, while the details were correct, it happened to her, not to me.

Bloom cites a lot of these old studies in the book. The problem is that these are often p-hacked and don’t replicate. For this reason, when reading books like this I usually look up these studies to see if they look solid. It’s this one: Becoming Famous Overnight: Limits on the Ability to Avoid Unconscious Influences of the Past, 1989). It’s a terrible study. Every p value is bad, Bloom should have checked, and not cited such bullshit:

The difference among conditions in the ability to discriminate between famous and new nonfamous names approached significance, F(2, 33) = 2.40 (MSe = .279), p < . 11.

An analysis of the latency of correctly rejecting nonfamous names revealed a marginally significant interaction between single versus dual task and type of nonfamous name, F(I, 30) = 3.76 (MSe = 66,529), p < .06.

This difference in criterion approached significance, F(I, 15) = 3.73, p < .07.

I am not even cherry-picking, these are all the p values reported in the 3-part article!

I’m not quite so skeptical. While I think that the relevance of neuroscience is often overblown, some of the results really do matter for psychological theory.

Just as one example, in research by Naomi Eisenberger and her colleagues, subjects have their brains scanned while they play a virtual ball-tossing game that they believe is with two other people.37 Actually, it’s a computer program, and it’s designed to give them the feeling of being excluded, by having the other characters toss the ball to one another, and leaving the human out.

This hurts. Being shunned is painful, and this study was designed to explore the theory that the pain of rejection shares deep commonalities with actual physical pain. And this is what the brain scanning found: Relative to those subjects who didn’t get socially shunned, people in the social exclusion condition had increased activation in parts of the brain such as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula, the same parts of the brain that are activated when feeling physical pain. This finding has a surprising (though controversial) consequence, which is that interventions that reduce one sort of pain should reduce the other, and indeed there is some evidence that drugs like Tylenol, designed to work on physical aches and pains, can also diminish the hurt of loneliness.38

Psychology doesn’t reduce to neuroscience, but neuroscience really can tell us interesting things about how the mind works.

It’s this one: Does Rejection Hurt? An fMRI Study of Social Exclusion (2003). Sounds terrible, fMRI and social psychology together is a recipe for disaster. However:

As predicted, group analysis of the fMRI data indicated that dorsal ACC (Fig. 1A) (x = –8, y = 20, z = 40) was more active during ESE than during inclusion (t = 3.36, r = 0.71, P < 0.005)

Basically all the p values they report are tiny, so it’s definitely not p-hacked but could still be fraudulent. The study apparently never mentions the sample size, but it seems to be n=13 by counting their scatterplot. Might be legit.

It turns out that only a small fraction of the sensory experience makes its way in; everything else is ignored and lost forever. In one famous study, reported in a paper titled “Gorillas in Our Midst,” subjects are shown a video in which people in white shirts and black shirts are standing in a hallway passing basketballs back and forth.24 The subjects’ task is to focus on the white shirts and count the passes they make. People don’t find this hard, but it does take all their attention. Here’s the twist: In the middle of the video someone dressed as a gorilla walks onto the scene, stops in the middle and pounds his chest, then walks off. About half of the subjects miss it, though the presence of the gorilla is screamingly obvious for anyone who is not told to focus on the passing of the basketballs.

We tend to be ignorant of these limitations. It feels like we are conscious of the world, not just a small sliver of it. It feels like we can attend to multiple things at the same time, rather than being forced to move our attention back and forth. Our limitations are harmless enough if we are writing emails when watching television or listening to a podcast while mowing the lawn. But they can be fatal in cases where something occasionally needs our full attention, such as driving. Talking on the phone, even using a hands-free device, slows our reaction time on the road, to an extent that is roughly the same as being legally intoxicated.25

That gorilla study was of course always heavily popularized, so let’s check it out: Gorillas in Our Midst: Sustained Inattentional Blindness for Dynamic Events (1999). P values seem good though, maybe because it was done by Christopher F. Chabris who is generally solid.

If you go to Wikipedia, you’ll find an entry called “List of Cognitive Biases,” and it goes on for a while, spanning from “agent detection” to “the Zeigarnik effect.”3 Some of these supposed biases are quite specific. There is, for instance, the “rhyme as reason” bias, which states that we are more likely to believe rhyming statements than nonrhyming equivalents (one such study finds that people are more persuaded by a sentence like “What sobriety conceals, alcohol reveals” than one like “What sobriety conceals, alcohol unmasks”).4 This bias is said to explain in part the acquittal of accused murderer O. J. Simpson, where the defense made the closing argument: “If the gloves don’t fit, you must acquit.” It rhymes, so it’s extra convincing.

The study is: Birds of a Feather Flock Conjointly (?): Rhyme as Reason in Aphorisms (2000). P values:

Analyses of the accuracy ratings indicated that, overall, there were no reliable differences in mean ratings between extant rhyming and nonrhyming aphorisms (5.51 and 5.45, respectively) or original and modified versions (5.63 and 5.35), p > .10 in both cases. However, participants in the control-instructions condition generated slightly higher ratings overall than those in the warning condition (5.68 and 5.26), Fp (1, 98) 4 2.79, p < .08, and Fi (1, 58) 4 2.63, p < .12. This marginal effect was moderated by a reliable Aphorism Type × Version × Instruction Condition interaction, Fp(1, 98) 4 7.84, p < .01, and Fi (1, 58) 4 5.58, p < .02. The relevant means are presented in Figure 1. Planned analytical comparisons (Keppel, Saufley, & Tokunaga, 1992) were used to investigate differences among the means. As we predicted, participants who were not cautioned to distinguish aphorisms’ semantic content from their poetic qualities (the control-instructions condition) assigned higher accuracy ratings to the original rhyming aphorisms than their modified counterparts (6.17 and 5.26), Fp (1, 98) 4 12.77, p < .01, and Fi (1, 58) 4 8.62, p < .03; however, they assigned comparable ratings to the original and modified nonrhyming aphorisms (5.79 and 5.51), Fp (1, 98) 4 1.21, p > .10, and Fi (1, 58) 4 0.82.

Participants in the warning condition exhibited a markedly different pattern of accuracy ratings. The original rhyming aphorisms were assigned reliably lower accuracy ratings in this condition than in the control condition (5.42 and 6.17), Fp (1, 98) 4 4.79, p < .05, and Fi (1, 58) 4 4.26, p < .05. In addition, in the warning condition, there were no reliable differences in participants’ ratings for original and modified versions of the extant rhyming aphorisms (5.42 and 5.17), Fp (1, 98) 4 0.96, and Fi (1, 58) 4 0.65, or of the extant nonrhyming aphorisms (5.14 and 5.36), Fp (1, 98) 4 0.75, and Fi (1, 58) 4 0.52.

It’s a maybe.

My colleague Shane Frederick developed questions where the wrong answer is quick and intuitive (System 1) and the right answer requires careful deliberation (System 2). These questions make up the Cognitive Reflection Test.19 Here are a couple of examples from a more recent version of this test.20

If you’re running a race and pass the person in second place, what place are you in?

Emily’s father has three daughters. The first two are named Monday and Tuesday. What is the third daughter’s name?

When faced with the first question, many people respond by saying “first place,” but if you think about it, it’s second place. The intuitive answer for the next question is “Wednesday,” but nope, it’s . . . Emily. If you got the wrong answer, you’re not dumb, you’re just not reflecting deeply. You’re going with your gut. You’re in thrall to System 1. The extent to which you rely on System 1 for such questions connects to other things of importance, such as how likely you are to believe conspiracy theories on social media21 and how likely you are to believe in God.22

I didn’t know there were more of these cognitive reflection test-type questions following the “intuitive wrong answer vs. analytic correct answer” pattern. The issue with these is that they are mainly tests of intelligence, not of system 1 vs. 2 theory.

But we don’t start off disgust sensitive. As Freud put it in Civilization and Its Discontents, “The excreta arouse no disgust in children. They seem valuable to them as being a part of their own body which has come away from it.”35 If left unattended, young children will touch and even eat all manner of disgusting things. In one of the coolest studies in all of developmental psychology, Rozin and his colleagues did an experiment in which they offered children under the age of two something that was described as dog feces (“realistically crafted from peanut butter and odorous cheese”). Most of them ate it.36

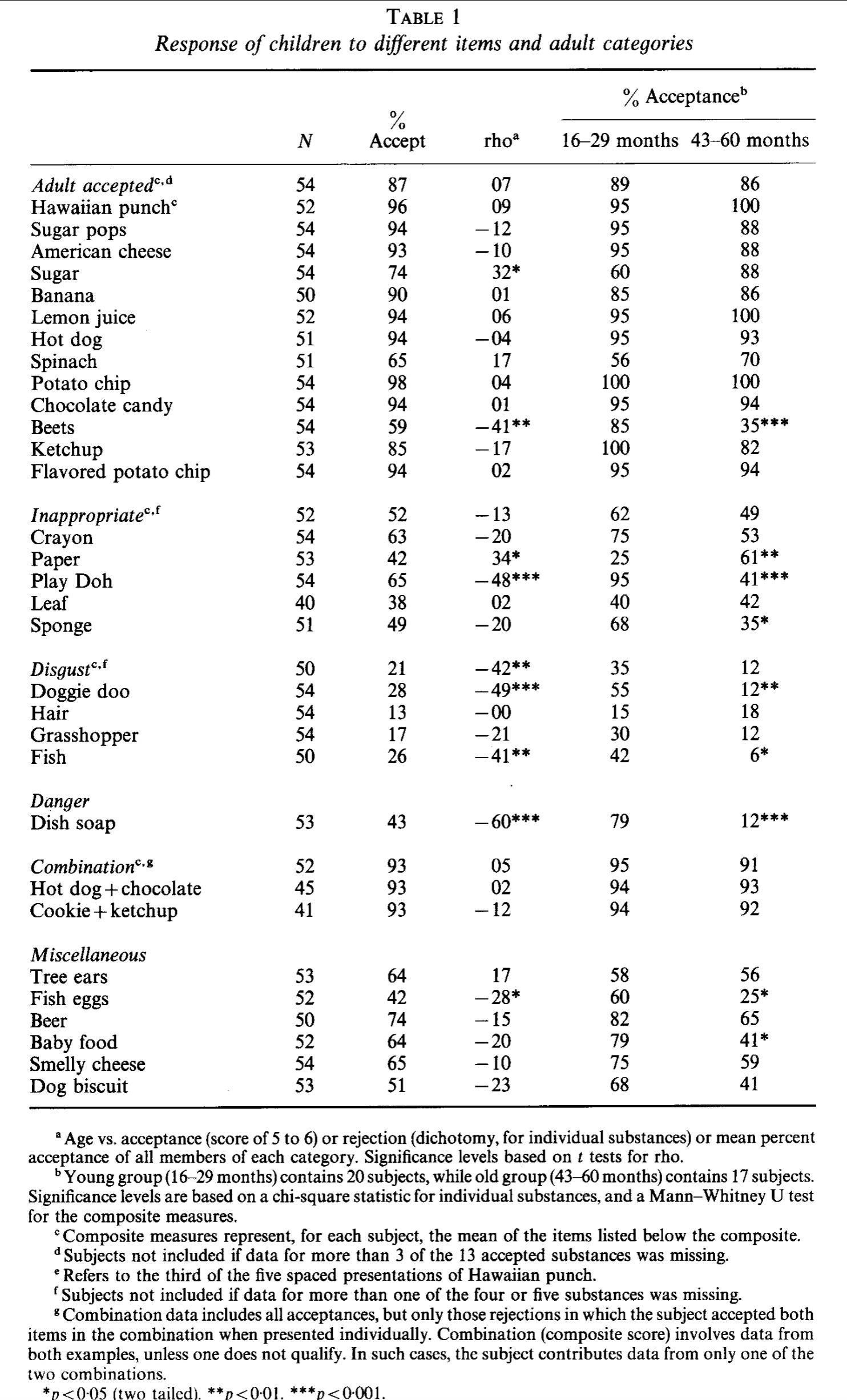

It’s this one: The child’s conception of food: differentiation of categories of rejected substances in the 16 months to 5 year age range (1986), and their table:

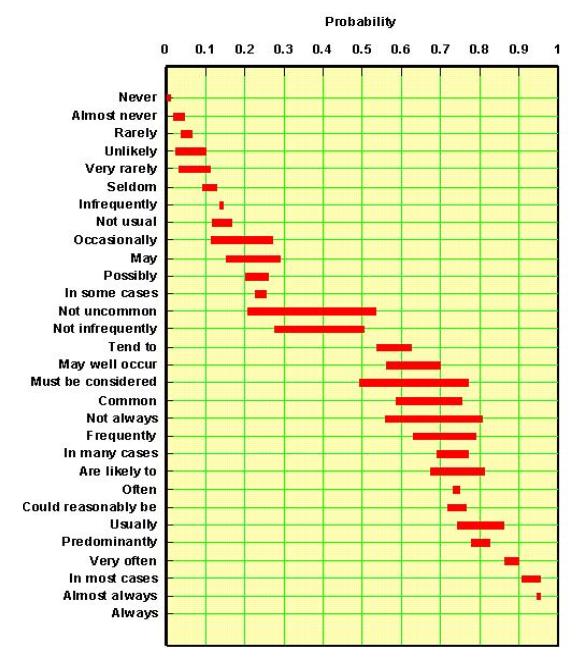

So yeah, doggie doo (poo) was indeed eaten by most children, but 55% is a poor “most”. If I tell you most men lose their hair by age 60, and you find some study showing this to be 55% of men, you would probably say I exaggerated it. Intuitively, most tends to get people to think of about say which values they think correspond to various vague numerical terms. Looks like this:

“In most cases” means about 90-95% chance.

The anthropologist Edward Westermarck proposed that humans solve this problem in a different way: We tend not to be sexually interested in those we are raised with as children.44 This disinterest overrides any conscious knowledge. You might know perfectly well that someone isn’t biologically related to you, but if you spent your childhood with him or her, it’s a libido killer. Conversely you might know perfectly well that someone is close genetic kin—as in the rare cases where someone meets, as an adult, a sibling that was separated from them at birth—but if you have never lived with that person when you were young, the idea of sex with them doesn’t necessarily gross you out.

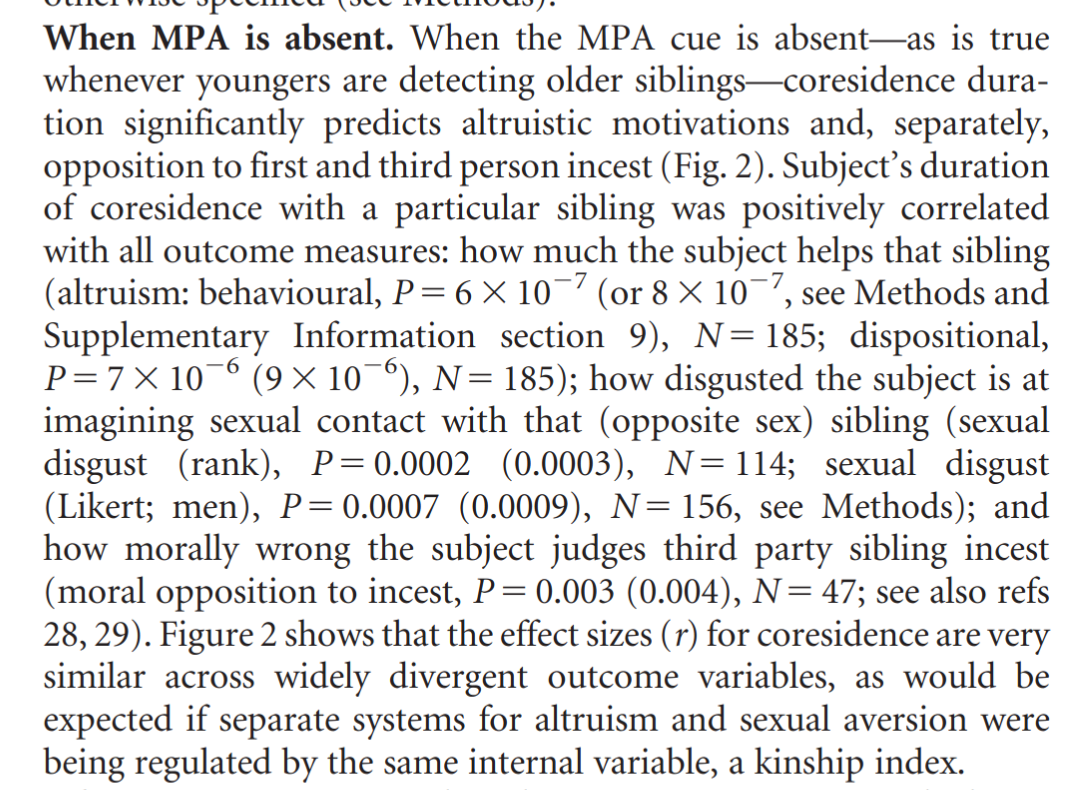

To explore the Westermarck hypothesis, the psychologist Debra Lieberman and her colleagues asked adults a series of questions—about whether they were raised with their siblings, how much they care about them, and how disgusted they are (if at all) at the thought of having sex with them. As predicted, duration of coresidence is the big factor—the longer you live with the sibling, the more sexual aversion.45

Sounds interesting given my prior summary of sexual relations between family members of adoption studies. It’s this study: The architecture of human kin detection (2007):

It checks out, tiny p values.

We are also, to a lesser extent, kind to the strangers we encounter. In many places in the world, if you stand on the street befuddled, someone will walk up and ask if you need directions, and if you scream for help, people will come. I’ve had strangers help push my car out of snow and done my own share of car pushing. If nobody gave to people asking for money on the street, people wouldn’t ask for money on the street.

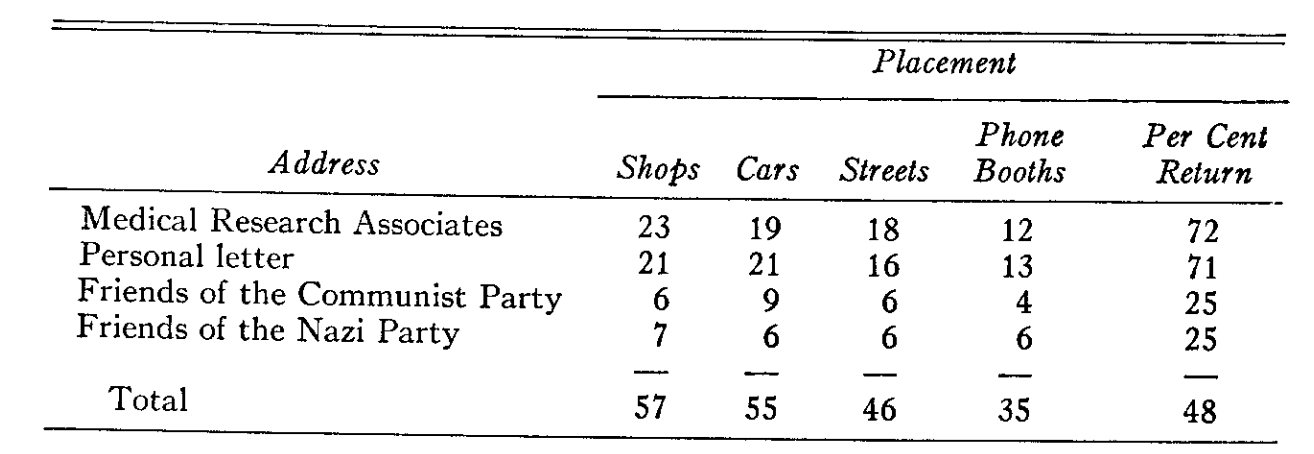

I live in Toronto now, but one study on this topic was done in my previous home of New Haven, Connecticut, by Stanley Milgram. He is better known for a famous experiment he conducted on obedience, which we’ll get to soon enough, but in 1965, Milgram was interested in kindness.62 He scattered stamped and addressed letters all over New Haven, dropping them onto sidewalks and placing them in telephone booths and other public places as if they had been forgotten. He found that most letters got to their destinations, which means that the good people of New Haven had picked them up and put them into mailboxes—simple acts of kindness that could never be reciprocated. The kindness was selective in a way that suggests a moral motivation—letters that had an individual’s name on the front, like “Walter Carnap,” tended to be mailed, but letters addressed to recipients like “Friends of the Nazi Party” were not.

Curious. It’s this one: The Lost-Letter Technique: A Tool of Social Research (1965).

Interesting that the results were the same for Nazis and Communist parties! I would guess the contrast would be very large these days.

But this is not the story that some social psychologists would tell. They will say that my review of their field missed an important discovery that shows we are nowhere near as smart as people like me think we are.

The discovery is social priming. Consider some truly striking findings. (Some of these might seem a bit crazy, but I’ll explain the theory behind them in a bit.) Sitting on a wobbly workstation or standing on one foot makes people think their romantic relationships are less likely to last.31 College students who fill out a questionnaire about their political opinions when next to a dispenser of hand sanitizer become, at least for a moment, more politically conservative.32 Exposure to noxious smells makes people feel less warmly toward gay men.33 If you are holding a résumé on a heavy clipboard, you will think better of the applicant.34 If you are sitting on a soft-cushioned chair, you will be more flexible when negotiating.35 Standing in an assertive and expansive way increases your testosterone and decreases your cortisol, making you more confident and more assertive.36 Thinking of money makes you less caring about other people.37 Voting in a school makes you more approving of educational policies.38 Holding a cold object makes you feel more lonely.39 Seeing words related to the elderly makes you walk slower.40 You are more likely to want to wash your hands if you are feeling guilty.41 Being surrounded by trash makes you more racist.42 And so on and so on.

Truly striking only in the credulity of the researchers involved. However, later he goes on to say:

We don’t live in this bizarro world. For the sake of argument, I’ve been assuming that these effects are real. But social priming effects are the most controversial in psychology. We talked about the replication crisis just before this chapter, describing how certain research practices have led to false positives—findings in the literature that are not true. This crisis has hit hardest in the domain of social priming, devastating what one critic called “primeworld.”50 Indeed, one of the items on my list is clearly fraudulent—the “finding” that being surrounded by trash makes you more racist was published by Diederik Stapel, who later admitted to making it up. As far as I know, none of the other findings are fraudulent, but they are all uncertain (including one that I was coauthor of), and several of them have failed to replicate.

Again, some instances of social priming might be robust, just subtle and hard to find. Now, there’s nothing wrong with subtle. I’ve always been fascinated with the potential connection between physical purity and moral purity,51 and some of the demonstrations of a link might hold up. Standing like Wonder Woman might not influence hormones, but it does seem to boost your confidence.52 Even if the effects only emerge in controlled laboratory conditions, the findings, if replicable, can tell us some interesting things about the mind.

But the subtlety of the effects suggests that they really don’t play much of a role in everyday life. They certainly don’t show us that consciousness is irrelevant. From a practical point of view, they might not matter at all.

Then why bother citing them? These should just be ignored, or shown as examples of scientific failure of social psychology. Is there any robust social priming effect like the above?

As an example—and sorry if you’ve heard this one before—check out this riddle:

A father and son are in a car accident. The father dies. The son is rushed to the hospital, he’s about to get an operation, and the surgeon says, “I can’t operate—that boy is my son!” How is this possible?

Answer: The surgeon is the boy’s mother. Well, duh. When I first heard the riddle, it was a real head-scratcher, but that was a while ago, and I would have thought it would no longer work now. Everyone knows that women can be surgeons. But a study done in 2021 found that only about a third of college students who had never heard this riddle before gave that answer.26 The students were either stumped or gave other answers. The surgeon could be the boy’s stepfather, adoptive father, or second father in a same-sex marriage. Other answers included “It could be a dream and not reality,” “While the son was in the operating room he died, and when he saw the surgeon, it was his dad’s ghost,” and “The ‘father’ killed could be a priest, because priests are referred to as fathers and members of the church are ‘sons.’”

Presumably, it’s not that university students in 2021 didn’t know that surgeons could be women. And yet, when they thought of a surgeon, they thought of a man, so much so that they entertained outlandish alternatives. This hints at a certain sort of duality between our considered views (“Of course women can be surgeons”) and what naturally comes to mind when given a riddle like this one (“Surgeons are men”).

Such implicit notions sway us in ways that matter. As one example, consider the study, mentioned earlier, in which psychologists put baseball cards up for sale on eBay.27 Sometimes the cards were held by a light-skinned hand and sometimes they were held by a dark-skinned hand. This has an effect: People’s maximum bids dropped about 20 percent for the darker hands. Other studies have been done in which résumés that are identical are sent out to different individuals, except that one is John Smith and the other is Jane Smith, or one is a member of the Young Republicans and the other a member of the Young Democrats, or one is white and the other Black, and so on. If people were just responding to the merits of the candidates, and ignoring factors such as sex, politics, and race, they should, on average, respond identically to these résumés. But they don’t; they are influenced by biases, in all sorts of ways, even when they believe themselves to be fair and egalitarian.28

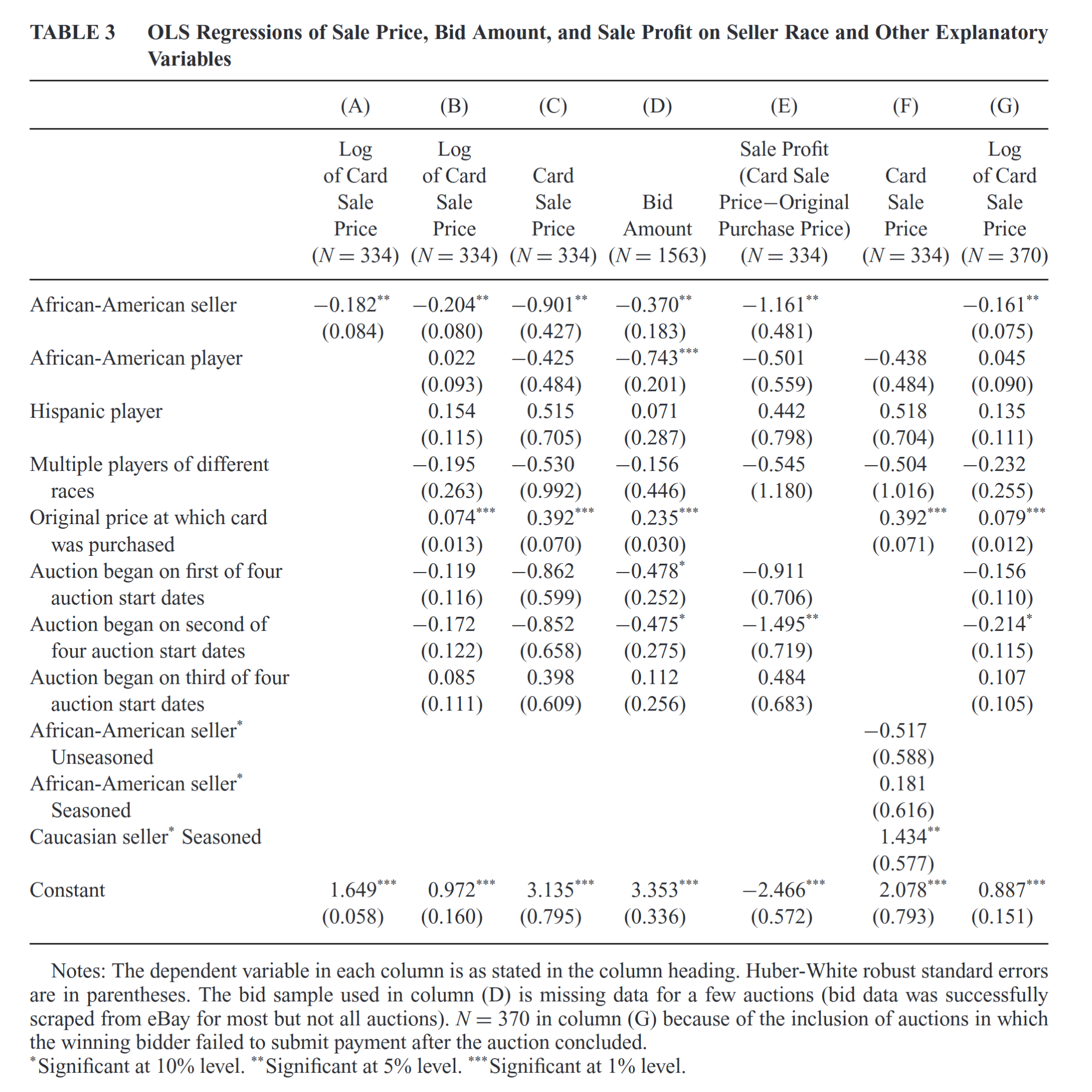

Bloom fails to understand the role of priors in cognition. Candidates are not magically made equal just because of some CV given rampant discrimination in standards for acquiring these. That’s why these resume studies are uninterpretable with regards to “taste discrimination”. Looking up that baseball card study, it’s this one: Race Effects on eBay (2015).

Typical economist p < .05 stuff. Shrug tier.

Some other tests don’t fare any better. One well-known personality test is the Rorschach Inkblot, where a person describes what they see in an ambiguous figure like the one below. (Fun fact: the inventor of this test, Hermann Rorschach,6 was obsessed with inkblots; his nickname in school, in Switzerland, was . . . Klex, or “inkblot”!)

This is a test that’s been used for psychiatric diagnosis, criminal cases, custody hearings, and other high-stakes decisions. But many psychologists and psychiatrists believe that it has little or no validity.7 It does remarkably poorly at predicting any outcomes that matter.

But that’s false. Rorschach tests do predict stuff, as does the Myers Briggs. It doesn’t matter what the initial theory was. Bloom should not be repeating such popular myths of psychologists.

We’ve seen that there is a relationship between IQ and various forms of kindness; this is true as well for these other traits.48 Lack of self-control is associated with a tendency to engage in all sorts of cruel acts, which is why drugs like alcohol, which loosen our inhibitions, are so often involved in the commission of violent crime.49 Psychopathy is associated with high impulsivity, while studies of extraordinary altruists, such as those who donate their kidneys to strangers, find that they are less impulsive than the rest of us.50

These points were anticipated by the philosopher Adam Smith long ago. In his book The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759, Smith discusses the qualities that are most useful to a person and comes up with the following (note that “superior reasoning and understanding” is what we are calling intelligence, and “self-command” is what we now call self-control). Smith writes:

The qualities most useful to ourselves are, first of all, superior reason and understanding, by which we are capable of discerning the remote consequences of all our actions, and of foreseeing the advantage or detriment which is likely to result from them: and secondly, self-command, by which we are enabled to abstain from present pleasure or to endure present pain, in order to obtain a greater pleasure or to avoid a greater pain in some future time. In the union of those two qualities consists the virtue of prudence, of all the virtues that which is most useful to the individual.51

Pretty interesting quote from Adam Smith.

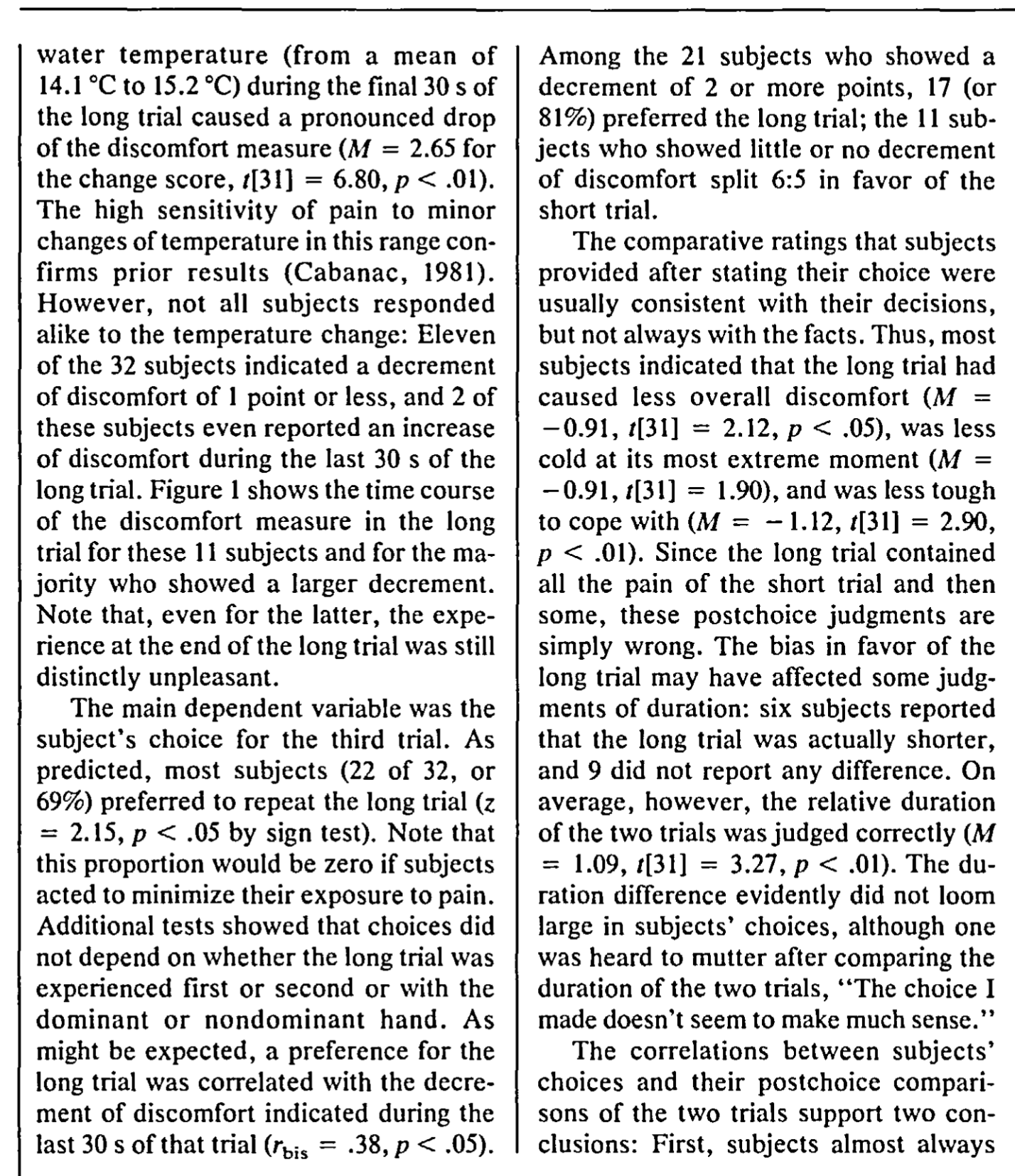

It turns out that when we think about past events, we tend to focus on two things—the peak (the most intense moment) and the ending. One study provides a dramatic illustration of this. Experimenters exposed subjects to differing levels of pain—by having them immerse their hands in freezing water—for different periods of time.68 Here were the trials:

- 60 seconds of moderate pain.

- 60 seconds of exactly the same moderate pain. Then, for 30 more seconds, the temperature is raised a bit, still painful, but less so.

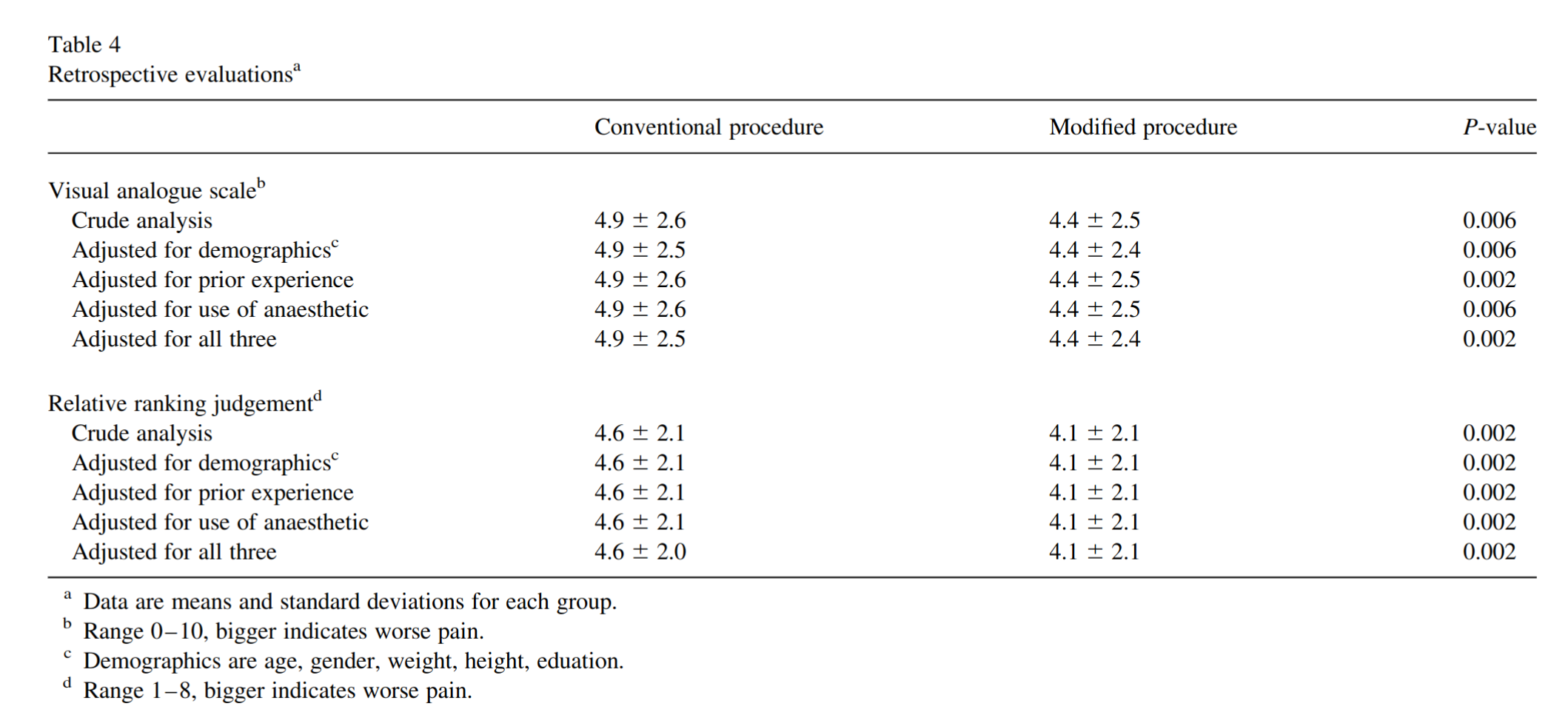

Which did subjects prefer? You might think A because, duh, less pain. But, no, they preferred B because of the better ending. In another study,69 Kahneman and his colleagues went outside of the lab. They tested volunteers who were undergoing a colonoscopy procedure (this was done at a time when these procedures were substantially more unpleasant), and, for half of the people, artificially prolonged the procedure, by leaving the scope inside them for an extra three minutes, not moving, which was uncomfortable but not painful. These people with the additional discomfort rated their experience as overall less unpleasant, just because it ended on a less painful note.

One of the classic Kahnemen works. But is that legit though? These studies are: 1) When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End (1993), and 2) Memories of Colonoscopy: A Randomized Trial (2003).

Maybe OK, but some p < .05’s.

The overall effect seems legit, but a lot of the other stuff in this study is p = .03 tier, even with sample sizes of many hundreds.

Finally, about his influences on writing the book:

I am grateful to the authors of three excellent books that had a big influence on me as I worked on the manuscript: The Idea of the Brain: The Past and Future of Neuroscience by Matthew Cobb; The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality by Kathryn Paige Harden; and Freud: Inventor of the Modern Mind by Peter D. Kramer. I am grateful as well to other scholars whose work I went back to over and over again, including Susan Carey, Frank Keil, and Elizabeth Spelke (on the topic of child development), Edward Diener (happiness), Julia Galef (rationality), Daniel Gilbert (social psychology), Joseph Henrich (culture), Steven Pinker (language, rationality), Stuart Ritchie (intelligence), and Scott Alexander (perception, clinical psychology). I know that some readers will want to know where to go to learn more about psychology—this paragraph is my answer.

The Paige-Harden/Ritchie influence shows in the discussion of behavioral genetics findings. This chapter is mostly pretty good, but it repeated the already disproven claim of large gene-environment interaction for heritability in the USA. I guess we have to wait another decade for this claim to die. The legacy of Eric Turkheimer.

Conclusions

Overall, this was an OK read. If I had read more recent alternative books trying to introduce the reader to psychology, I would be able to compare them. Still, it includes citations to lots of low quality research. I don’t think psychologists should be writing books dubious research like that. Maybe Bloom should have paid Ritchie to go through all the research cited with a comb to avoid the worst p = .07 marginal significance stuff. The chapters on differential psychology and behavioral genetics were mostly pretty decent, which is probably far better than most psychology textbooks. I think the book covered too much history, not sure people need to know about details of Skinner’s studies or the history of that debate.