We can read in many outlets that the reason autism is increasing in prevalence is that clinicians are becoming more aware of it. The idea being that autism was already widespread, they are simply acknowledging it more or getting better at spotting it. For instance, here’s an article from StatNews (what does this have to do with statistics? I don’t know):

The main reason we are finding more autism is simple: Clinicians are getting better at spotting what was always there. There is no simple test for autism, so diagnosing it requires substantial training in observational techniques. As a result, diagnosis can vary significantly depending on the population and the competence of clinicians. The CDC reports significant variations in autism rates from state to state and even from one school district to another. Yet there is little biological evidence to explain this. In another example of the variation, prior reports found more autism in white children. [picture from StatNews]

This would be in line with the general mental health awareness trend, where everybody must at all times talk more about mental health. Here I will document that while this story is partially true, it is true in a misleading way. Namely, the main reason autism diagnoses are increasing is that diagnoses are being given more liberally. Other mental problems are increasingly being moved into the autism category and the threshold for receiving a diagnoses is declining.

Let’s begin:

- King, M., & Bearman, P. (2009). Diagnostic change and the increased prevalence of autism. International journal of epidemiology, 38(5), 1224-1234.

Methods Retrospective case record examination of 7003 patients born before 1987 with autism who were enrolled with the California Department of Developmental Services between 1992 and 2005 was carried out. Of principal interest were 631 patients with a sole diagnosis of mental retardation (MR) who subsequently acquired a diagnosis of autism. The outcome of interest was the probability of acquiring a diagnosis of autism as a result of changes in diagnostic practices was calculated. The probability of diagnostic change is then used to model the proportion of the autism caseload arising from changing diagnostic practices.

Results The odds of a patient acquiring an autism diagnosis were elevated in periods in which the practices for diagnosing autism changed. The odds of change in years in which diagnostic practices changed were 1.68 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.11–2.54], 1.55 (95% CI 1.03–2.34), 1.58 (95% CI 1.05–2.39), 1.82 (95% CI 1.23–2.7) and 1.61 (95% CI 1.09–2.39). Using the probability of change between 1992 and 2005 to generalize to the population with autism, it is estimated that 26.4% (95% CI 16.25–36.48) of the increased autism caseload in California is uniquely associated with diagnostic change through a single pathway—individuals previously diagnosed with MR.

Conclusion Changes in practices for diagnosing autism have had a substantial effect on autism caseloads, accounting for one-quarter of the observed increase in prevalence in California between 1992 and 2005.

-

Coo, H., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Lloyd, J. E., Kasmara, L., Holden, J. J., & Lewis, M. S. (2008). Trends in autism prevalence: diagnostic substitution revisited. Journal of Autism and developmental Disorders, 38, 1036-1046.

There has been little evidence to support the hypothesis that diagnostic substitution may contribute to increases in the administrative prevalence of autism. We examined trends in assignment of special education codes to British Columbia (BC) school children who had an autism code in at least 1 year between 1996 and 2004, inclusive. The proportion of children with an autism code increased from 12.3/10,000 in 1996 to 43.1/10,000 in 2004; 51.9% of this increase was attributable to children switching from another special education classification to autism (16.0/10,000). Taking into account the reverse situation (children with an autism code switching to another special education category (5.9/10.000)), diagnostic substitution accounted for at least one-third of the increase in autism prevalence over the study period.

Thus, in the years they changed the diagnostic criteria, there is a new spike in prevalence. In this case, it appears 26% of the increased rate in autism is due to reclassifying people previously diagnosed with “MR”, that is, mental retardation (very low intelligence), or “special education” (meaning about the same). No one wants to be told their child is retarded or needs to go to special education (loser/weirdo school). Parents know that’s a near hopeless case. If instead you are told your child is autistic, there is hope (just read any popular article about billionaire ‘autists’). And of course, a lot of money for those working in the industry even though there is no real treatment for autism that works.

- Arvidsson, O., Gillberg, C., Lichtenstein, P., & Lundström, S. (2018). Secular changes in the symptom level of clinically diagnosed autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(7), 744-751.

Background The prevalence of autism has been reported to have increased worldwide. A decrease over time in the number of autism symptoms required for a clinical autism diagnosis would partly help explain this increase. This study aimed to determine whether the symptom level of clinically diagnosed autism cases below age 13 had changed over time.

Methods Parents of Swedish 9-year old twins (n = 28,118) participated in a telephone survey, in which symptoms and dysfunction/suffering related to neurodevelopmental disorders [including autism, but also attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), and Learning Disabilities (LD)] in their children were assessed over a 10-year period. Survey data was merged with the National Patient Register containing clinically registered autism diagnoses (n = 271).

Results In individuals who had been clinically diagnosed with autism before the age of 13, the symptom score for autism decreased on average 30% over more than a decade in birth cohorts 1992–2002. There was an average decrease of 50% in the autism symptom score from 2004 to 2014 in individuals who were diagnosed with autism at ages 7–12, but there was no decrease in those diagnosed at ages 0–6.

Conclusions Over time, considerably fewer autism symptoms seemed to be required for a clinical diagnosis of autism, at least for those diagnosed after the preschool years. The findings add support for the notion that the observed increase in autism diagnoses is, at least partly, the by-product of changes in clinical practice, and flag up the need for working in agreement with best practice guidelines.

In other words, if previously you would have been classified as kinda autistic, but not really clinically so, you are now more likely to be given a mild autism diagnosis (“autism spectrum disorder”). This decreasing standard means that those classified as autistic are relatively less autistic compared to the “neurotypicals”. Or, we might say, the autists are getting less autistic. In prior times, autistics were those screaming children you had to lock up in an institution as they were often non-verbal.

We can also see the changing standard of diagnosis by comparing people with autism diagnoses vs. neurotypicals on various other traits. If they are getting less distinct, we know that the diagnostic criteria are becoming less strict, or at least, it is including different kinds of people than previously.

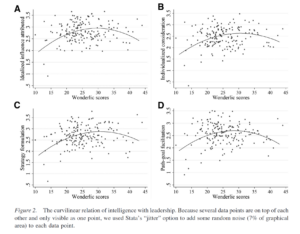

- Rødgaard, E. M., Jensen, K., Vergnes, J. N., Soulières, I., & Mottron, L. (2019). Temporal changes in effect sizes of studies comparing individuals with and without autism: a meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry, 76(11), 1124-1132.

Objective To examine the correlation between publication year and effect size of autism-control group comparisons across several domains of published autism neurocognitive research.

Data Sources This meta-analysis investigated 11 meta-analyses obtained through a systematic search of PubMed for meta-analyses published from January 1, 1966, through January 27, 2019, using the search string autism AND (meta-analysis OR meta-analytic). The last search was conducted on January 27, 2019.

Study Selection Meta-analyses were included if they tested the significance of group differences between individuals with autism and control individuals on a neurocognitive construct. Meta-analyses were only included if the tested group difference was significant and included data with a span of at least 15 years.

Data Extraction and Synthesis Data were extracted and analyzed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline using fixed-effects models.

Main Outcomes and Measures Estimated slope of the correlation between publication year and effect size, controlling for differences in methods, sample size, and study quality.

Results The 11 meta-analyses included data from a total of 27 723 individuals. Demographic data such as sex and age were not available for the entire data set. Seven different psychological and neurologic constructs were analyzed based on data from these meta-analyses. Downward temporal trends for effect size were found for all constructs (slopes: –0.067 to –0.003), with the trend being significant in 5 of 7 cases: emotion recognition (slope: –0.028 [95% CI, –0.048 to –0.007]), theory of mind (–0.045 [95% CI, –0.066 to –0.024]), planning (–0.067 [95% CI, –0.125 to –0.009]), P3b amplitude (–0.048 [95% CI, –0.093 to –0.004]), and brain size (–0.047 [95% CI, –0.077 to –0.016]). In contrast, 3 analogous constructs in schizophrenia, a condition that is also heterogeneous but with no reported increase in prevalence, did not show a similar trend.

Conclusions and Relevance The findings suggest that differences between individuals with autism and those without the diagnosis have decreased over time and that possible changes in the definition of autism from a narrowly defined and homogenous population toward an inclusive and heterogeneous population may reduce our capacity to build mechanistic models of the condition.

The important part here is to note that schizophrenia, which has seen no prevalence increase, shows no changes over time. Again, no one wants their child to be given a schizophrenia diagnosis. Even with all the lying about schizophrenics not being violent, stereotypes don’t change that much as reality provides too much contrary information.

This kind of trend in mental health shows how responsive psychiatry is to consumer demand. This messes with the scientific data and thus science. Science should be trying to carve nature at its joints, not trying to make parents happy by changing the diagnoses of their children. We don’t make up new categories of non-cancer and tell cancer patients that’s what they have. And worse, we get to listen to all these popular articles saying that the autism prevalence is definitely just due to society becoming more welcoming when really, scientists and clinicians are cooking the books. Such battles for threshold are a natural result of trying to split people into discrete groups (autistic or not) instead of considering autism just another normal-ish distribution that each person has a place in. I understand the human impulse to make parents happy, of course, but who is this really helping in the long run?

Ideally, we would invent treatments for autism. This is going to be difficult in practice given the very large genetic influence on autism.

- Tick, B., Bolton, P., Happé, F., Rutter, M., & Rijsdijk, F. (2016). Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: a meta‐analysis of twin studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(5), 585-595.

Results The meta-analysis correlations for monozygotic twins (MZ) were almost perfect at .98 (95% Confidence Interval, .96–.99). The dizygotic (DZ) correlation, however, was .53 (95% CI .44–.60) when ASD prevalence rate was set at 5% (in line with the Broad Phenotype of ASD) and increased to .67 (95% CI .61–.72) when applying a prevalence rate of 1%. The meta-analytic heritability estimates were substantial: 64–91%. Shared environmental effects became significant as the prevalence rate decreased from 5–1%: 07–35%. The DF analyses show that for the most part, there is no departure from linearity in heritability.

Conclusions We demonstrate that: (a) ASD is due to strong genetic effects; (b) shared environmental effects become significant as a function of lower prevalence rate; (c) previously reported significant shared environmental influences are likely a statistical artefact of overinclusion of concordant DZ twins.

There is likely little parents can do currently to avoid having autistic children, other than not being autistic themselves (more precisely, having high polygenic scores for autism). This lack of family-related causation would also mean that social interventions aren’t likely to be very useful. Instead, if one wants to do something about this, one would probably have to try more risky, direct biological interventions during the fetal stage (experiment on pregnan women). That doesn’t sound like a study that is going to be approved any time soon (not without reason!). Especially not if we cannot even agree that autism is something you generally want to avoid at least the worst parts of, and instead want to glamorize it, or say it’s just another way of being. The simple story is that autistics do worse in society in general, they are less happy, more likely to have other diagnoses, more likely to fail at jobs, live on benefits, fail at forming relationships, and so on. These negative outcomes are regrettable but due to their inability to properly cooperate with other humans, as well as shared genetics with other mental problems.

There is, however, a genetic solution. One could use embryo selection to reduce the chances of having an autistic child. Probably many prospective autistic parents will be seeking out this option in the near future. Genetic prediction models for autism are not too bad currently, and surely will improve fast as genetic datasets become larger. From a human achievement perspective, there is a conondrum here. Given the outsized achievement of the highly intelligent autists on scientific and technological progress, but with personal costs, we might deprive our species of socially valuable genetics using such selection. I consider this a big worry for this technology and something that is hard to deal with from a libertarian perspective. Even if one wants to ban strong selection against autism, it will be very difficult to enforce as prospective parents can simply fly somewhere else for the treatment. The situation for autism is thus unlike the case with intelligence where more is almost always better. This is something that bioethicists should be debating.