What is a taboo? Well, the dictionaries tell us (according to GPT4):

- Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th Edition (2003): “A prohibition imposed by social custom or as a protective measure.”

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition (1989): “A social or religious custom prohibiting or restricting a particular practice or forbidding association with a particular person, place, or thing.”

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition (2000): “A ban or an inhibition resulting from social custom or emotional aversion.”

(I picked older entries to avoid recent dictionary editing activism.)

What about taboos in science? There’s a long history of writing on this, but not much empirical research. For instance, Edward Sagarin wrote a book in 1980 called Taboos in Criminology. It’s unavailable anywhere I can find (please send an electronic copy if you can get it), but the summary will not surprise the modern reader:

Science and society, through intellectual and political perspectives, set limits on the propriety of certain scientific research. While this may bother those who believe that science should be unfettered in its search for truth, the real world is governed by prevalent social values, ideologies, and political policies which determine acceptable scientific enterprises and findings. In criminology, examples of unpopular orientations are many. Foremost is the link of crime to the factors of genes, biology, race, ethnicity, and religion. Those who contend, for example, that a link exists between race or ethnicity and crime, irrespecitve of social oppression, must be willing to withstand charges of racism, antisemitism, and bigotry. Such findings also challenge social policy orientations that attack poverty, unemployment, and social oppression as the roots of a high percentage of certain types of crime. The taboos imposed by a given society upon criminological research must be taken into account when proceeding into research areas where the taboos apply. While such taboos should not intimidate scientists to avoid research in certain areas, researchers should be aware of the volatile nature of the material with which they are dealing, such that findings are offered with special care and circumspection. It is inexcuseable for a scientist to publish findings that challenge prevalent social values without providing reliable, valid, and extensive empirical support. On the other hand, to avoid certain research because of its volatile nature or to suppress certain scientific findings because they might be unpopular is to allow the perpetuation of social myths that undermine the development of a more rational social system.

Glenn Loury even wrote a commentary on this during the 1990s ‘political correctness’ debate, taboo by another name.

Approaching the topic with even more distance, Philip Tetlock — of forecasting fame — discussed the use of “forbidden base rates” in 2000:

Forbidden base rates refer to any statistical generalization that devoted Bayesians would not hesitate to enter into their probability calculations but that deeply offends a religious or political community. The primary obstacle to using the putatively relevant base rate is not cognitive, but moral. In a society committed to racial, ethnic, and gender egalitarianism, forbidden base rates include observations bearing on the disproportionately high crime rates and low educational test scores of certain categories of human beings. Putting the accuracy and interpretation of such generalizations to the side, people who use these base rates in judging individuals are less likely to be applauded for their skills as good intuitive statisticians than they are to be condemned for their racial and gender insensitivity

Perhaps the most bullet-biting living philosopher, Neven Sesardić, wrote that, actually, police do and should use such base rates. Their use in the court system would surely be more controversial, but it cannot easily be attacked on rationality grounds.

With this historical review done, a few years ago, this gem was published:

- Jackson Jr, J. P., & Winston, A. S. (2021). The mythical taboo on race and intelligence. Review of General Psychology, 25(1), 3-26.

Recent discussions have revived old claims that hereditarian research on race differences in intelligence has been subject to a long and effective taboo. We argue that given the extensive publications, citations, and discussions of such work since 1969, claims of taboo and suppression are a myth. We critically examine claims that (self-described) hereditarians currently and exclusively experience major misrepresentation in the media, regular physical threats, denouncements, and academic job loss. We document substantial exaggeration and distortion in such claims. The repeated assertions that the negative reception of research asserting average Black inferiority is due to total ideological control over the academy by “environmentalists,” leftists, Marxists, or “thugs” are unwarranted character assassinations on those engaged in legitimate and valuable scholarly criticism.

It’s hard to know whether to accuse the authors of dishonesty or delusion. Nevertheless, we decided to take an empirical approach, and actually survey people to ask about what they consider taboo topics. So, to our new study:

- Pesta, B., Kirkegaard, E. O. W., & Bronski, J. (2024). Is Research on the Genetics of Race / IQ Gaps “Mythically Taboo?”, OpenPsych. https://doi.org/10.26775/op.2024.04.15

Jackson and Winston (“JW;” 2021) recently argued that no real taboos exist regarding the study of potential genetic links between race and IQ test scores. Instead, the authors essentially claimed that researchers in this area have protested too much. JW offered several arguments that presumably supported their claims, which we rebut here first. Empirically, however, we wondered just how “relatively taboo” this topic might be among Americans in general. Via Prolific.com, we surveyed 507 representative Americans on this issue. Our survey comprised 33 “taboo topics” (e.g., whether pedophilia is harmful), wherein each participant subjectively rated “tabooness” on five-point Likert scales. We found that the potential genetic basis of race / IQ gaps was the tabooest item in our survey. In fact, this topic was rated “more taboo” than were items regarding incest and even pedophilia. Further, the rank-ordering of “tabooness” was highly stable across the various demographic groups we looked at in our survey. At least among a (relatively large) representative sample of American adults, research on the genetics of race / IQ gaps is very strongly taboo. We conclude by discussing how our survey results further dampen JW’s claim that the taboo is real rather than mythical.

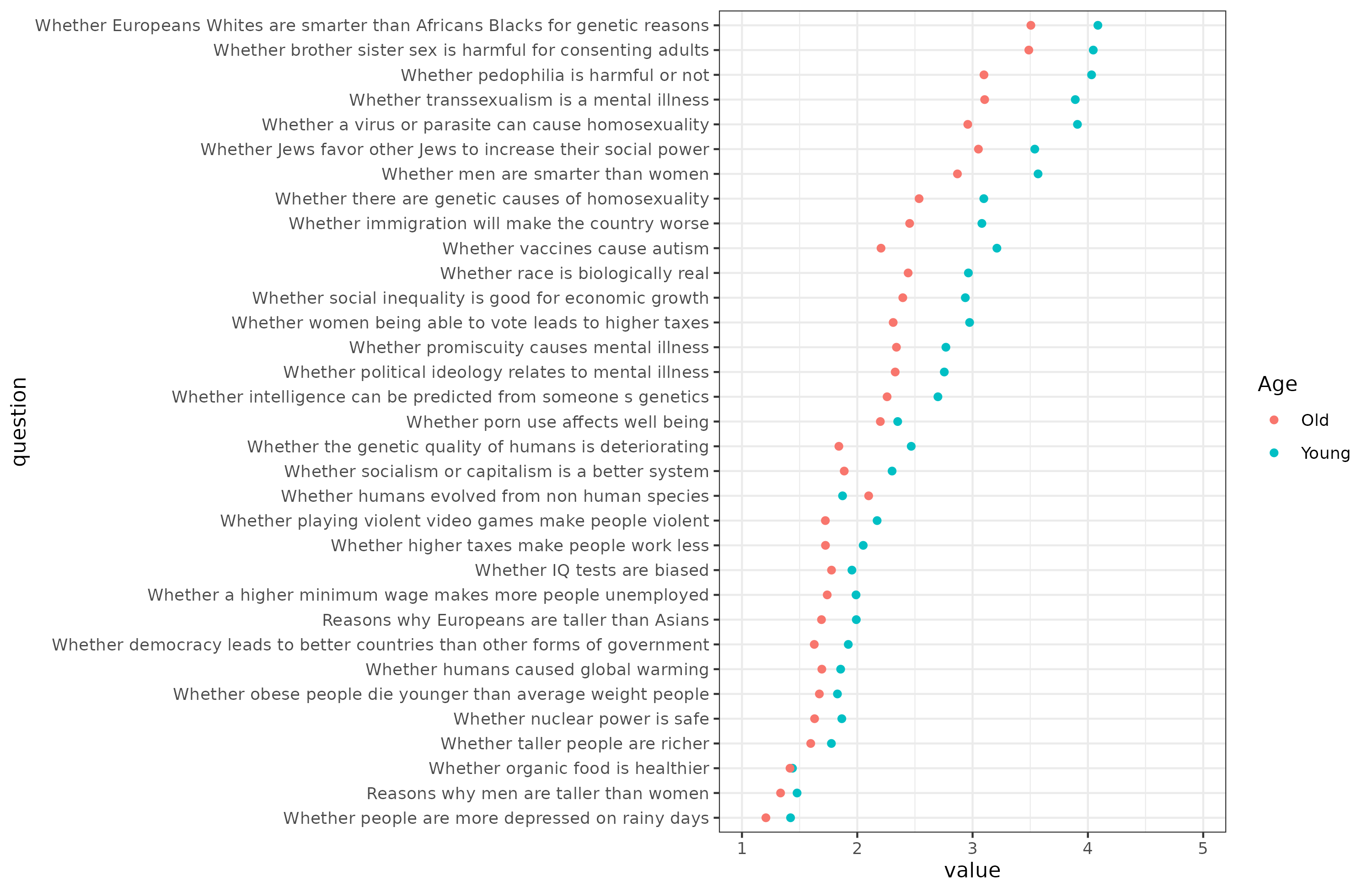

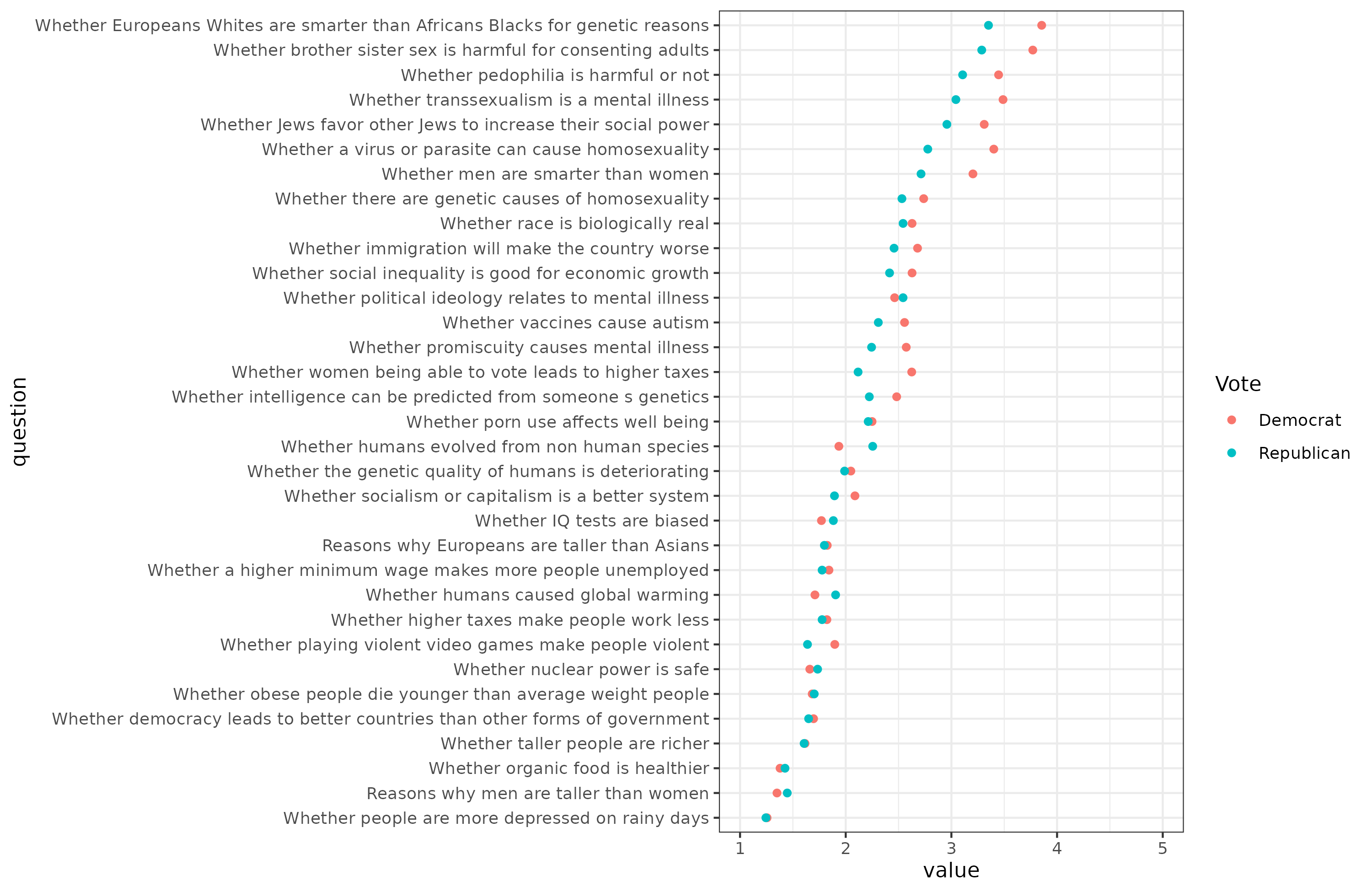

The specific prompt was: “Of the following questions, please indicate how taboo you think the question is”, with 5 options from “not at all taboo” to “extremely taboo”. We tried to include a wide variety of questions, some taboo, and some not taboo. The results look like this:

Thus, of our set of 29 scientific topics or questions, the most taboo was “Whether European Whites are smarter than African Blacks for genetic reasons”. It outranks even topics we intentionally included to compete for the top position including incest, pedophilia, gay germ theory, Jewish ethnocentrism as route to power, and mental illness in transsexuals.

It would appear that if the future of Western civilization depends on debunking this falsehood as per Nathan Cofnas, the future is indeed bleak.

Next we checked whether various subgroups of the sample agreed, and the answer was a resounding yes. For instance, men and women:

People of all races:

The young and the old:

And those of different politics:

And even those high or low in scientific knowledge (measured by a 7-item test):

The correlation between all sets of estimates was over .90, approaching 1.00 when the samples were relatively large (sampling error causes bias towards 0). Though, it should be noted that some groups find things more taboo in general than others: Democrats more than Republicans, the Young more than Old. There are also some dispersion effects, e.g., those high in science knowledge varied a bit more in their taboo ratings than those low in science knowledge.

One could attempt to claim that, though regular American adults have a strong perception of high vs. low tabooness of various questions, this might fail to generalize to scientists. This is not very likely, as “given the strong convergence between all identity groups surveyed, that the academic research community significantly differs from the pattern found here (see also the lack of results for our scientific knowledge variable)”.

It would seem as the collective scientific endeavor of humanity becomes more centralized, especially since the 1960s, social taboos become stronger and more uniform. The result of this is that there’s very little possibility of doing science on taboo topics. Since taboos do not necessarily reflect truthfulness, this is a very serious limitation of the centralization of science. What can be done to reduce the biasing effect of taboos on science?