Administering physical (corporal) punishment has a long history. Public flogging or whipping used to be commonplace, and now they are mostly illegal, and we regard foreign countries who employ these as backwards. In fact, the history much longer than that because non-human animals also use it. Do you think mother dog or cat is going to sit down and explain things to her puppies? I grew up in the countryside with dogs and cats, so I’ve seen plenty of animal parenting. Mainly, when puppies or kittens misbehave, the mother will either bark ‘yell’ at them, snap at them, growl and the like. In case this doesn’t work, the mother will sometimes bite them in a way that doesn’t cause any long-lasting damage, but is painful so as to induce a deterrence or learning effect. You can find many people telling you that if your dog has been particularly bad, you should bite its ear as a punishment in order to mimic this natural behavior. Now, searching around online, it was difficult to find good writings on this. There’s thousands of dog/cat sites, Reddit posts, Quoras and so on. The academic literature wasn’t impressive either, though one can read reviews of dog training methods saying things like:

Several owner–dog interaction variables were important to Taiwanese dogs’ aggressive responses, with physical punishment being the most prominent: dogs subjected to physical punishment for undesirable behaviors scored significantly higher on all three aggression subscales. The direction of the causal relationship between dog aggression and physical punishment cannot be ascertained; owners might be more inclined to punish aggressive dogs or dogs might behave more aggressively after being physically punished. Similar relationships were reported in some previous studies (Takeuchi et al., 2001; O’Sullivan et al., 2008b; Tami et al., 2008). However, Perez Guisado and Munoz-Serrano (2009) discovered an opposite trend (dogs that were physically punished scored lower on dominance aggression) and concluded that physical punishment could be the most effective way of avoiding dominance aggression. Neither our study nor previous studies (Takeuchi et al., 2001; O’Sullivan et al., 2008b; Tami et al., 2008) support this proposition. That dogs that are physically punished are more aggressive could simply reflect a higher tendency for dog owners to physically discipline more aggressive dogs. Nonetheless, the fact that they continued to behave aggressively should cast doubt on the effectiveness of physical punishment in reducing dog aggression. We also cannot rule out the possibility of physical punishment causing dogs to become more aggressive. The benefit of using physical punishment on dogs should therefore be evaluated more carefully.

Bad dogs get beaten, or beating a dog makes it bad, or both? This issue comes up in the behavioral genetics literature sometimes, and occasionally, some of the intellectuals will talk about various forms of corporal punishment as deserving another look (e.g. Robin Hanson), whether as part of parenting or criminal justice. These are really two sides of the same coin, if we consider the state to be a kind of parent and the citizens its children. Take this Richard Hanania tweet from March:

Or the most recent case of Malcolm Collins who:

And that’s the headline.

It was only in very recent history that Western countries decided that the state most protect children against their parents administering even light corporal punishment:

Why was it banned? I think there are two parts. First, the academics say it’s bad, and they point to correlations between use of corporal punishment and aggression in humans. Second, it’s easy to find horrific situations of parental abuse.

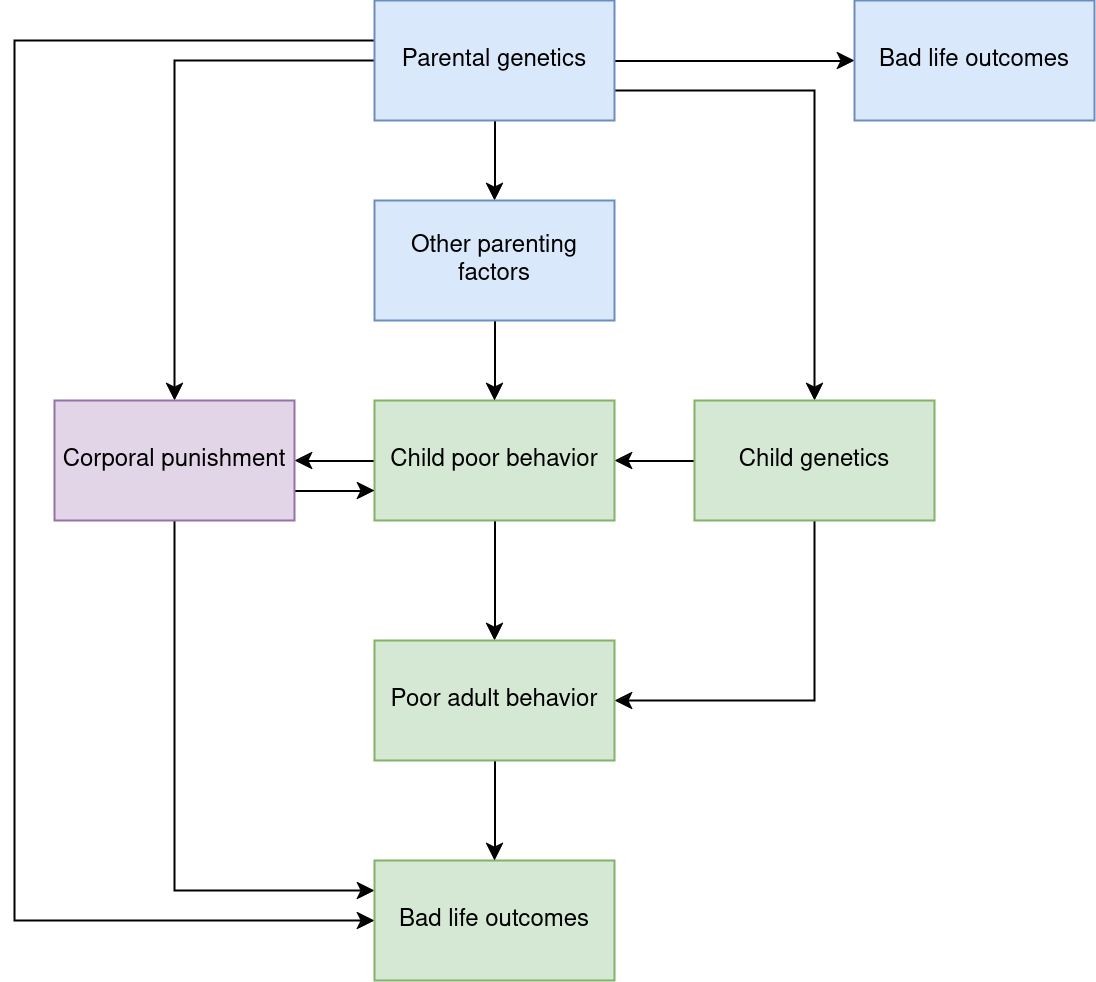

As you can imagine, the evidence about causality is not strong. How do the researchers know that corporal punishment caused the children’s later problems, and not poorly behaving children causing their parents to punish them more? In general, they don’t, they just assume this in line with the blank slate ideology. We could, however, draw up a diagram to make things more clear:

I’ve colored the parent-related variables in blue, the children related in green, and purpose for the mixed one. The arrows show possible paths of causation. One can make it more complicated, but I think the above covers most of the pathways we can think of. In a typical study, some aspects of the parents are measured, their education levels, incomes, and their parenting styles, including use of corporal punishment. For the children, usually they report their own behavior, and sometimes researchers ask their parents or teachers to rate the child’s behavior. In other cases, data from the school is used, e.g. detentions or grades. If the children have grown up, usually one looks at the most obvious outcomes like their education levels or sentences. Not every study measures every aspect, and sometimes studies just ask the (adult) children what their parents did to them in childhood. Whatever the exact variables measured, most research ignores the multiple possible pathways we see in the diagram above.

Behavioral genetics teaches us that most parent-child correlations are due to genetic similarity. So if we measure life outcomes in the parents, and in their children, the causal path is mainly through genetics. From this genetic perspective, there isn’t any causal path from corporal punishment to bad life outcomes, this association happens because genetically caused poor child behavior induces parents to try more extreme punishment methods to correct the behavior. In other words, bad dogs get punished.

But how can we be sure? Well, we could randomize parents to receive different parental advice including whether to use corporal punishment. Given the list of countries above that ban this entirely, this might be a difficult study to carry out. However, USA is not on the list above, and that’s because it’s still legal:

In fact, even teachers using it appears to be legal in about half the states. So conceivably someone could do a randomized controlled trial, and in some years we would know the answer. There are in fact a number of such trials where the treatment group is given advice not to use corporal punishment. The trouble with most of these is that they go like this 2016 study:

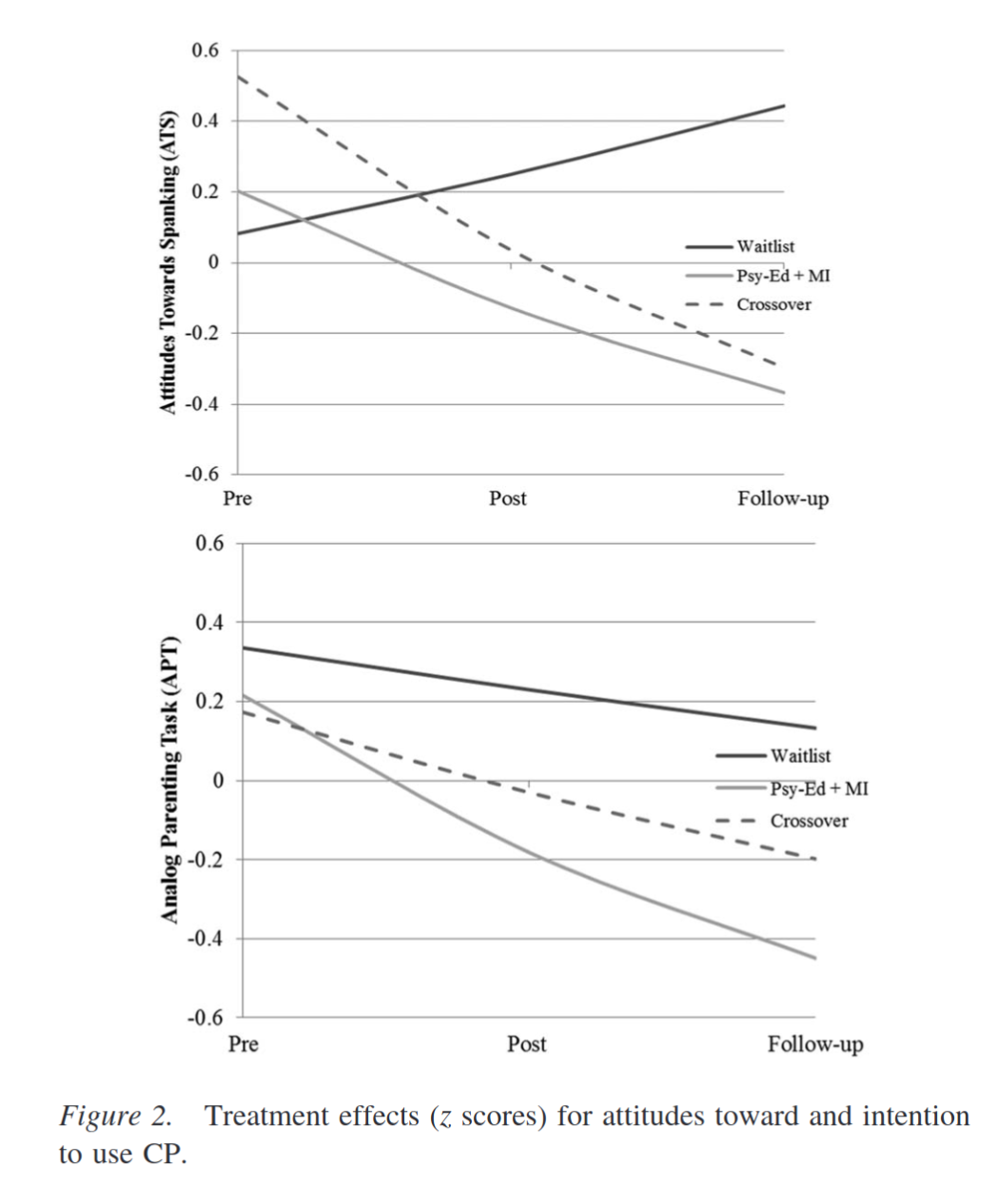

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a motivational interviewing (MI) approach in changing positive attitudes toward corporal punishment (CP), behavioral intentions, and behavior. CP has been linked to a variety of negative outcomes for children, and parents’ attitudes toward CP strongly predicts its use. Five brief interventions have been reported in the literature designed to target CP attitudes. The current study adopts a novel approach by evaluating the effects of a brief, psycho-educational intervention incorporating aspects of MI. Method: Forty-three mothers of children ages 3 to 5 completed 1 motivational psycho-education session. Participants were randomly assigned to intervention or waitlist, completing assessments at baseline, postintervention, and 1-month follow-up. After follow-up, the waitlist condition crossed over, completing the intervention and further assessments. Results: The intervention was associated with greater reductions in CP attitudes and intentions versus the waitlist; these effects were replicated in the crossover group. Further, participants’ in-session change-talk predicted greater changes in CP attitudes. The effect size of the current approach was stronger than the prior interventions. Conclusions: MI is a promising approach to address parental use of CP, though this approach needs replication with a larger sample. Several ways of incorporating this approach on a wider scale are considered.

Children’s actual behavior appears not to have been measured here, but parents’ attitudes were:

So, if we ignore the tiny sample size (the p value for the above is good, however), it appears that telling parents not to spank their children makes them report lower willingness to do so when you ask them again later. We don’t know if they actually do it less, or whether it was just talk. Are there some brave souls that went against the flow and looked at the causal evidence, and maybe even evidence that spanking might actually be good? Yes.

- Larzelere, R. E., Reitman, D., Ortiz, C., & Cox Jr, R. B. (2023). Parental punishment: Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater. In Ideological and Political Bias in Psychology: Nature, Scope, and Solutions (pp. 561-583). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Anna’s Archive]

Over the past several decades, the use of punishment as a strategy to discipline children has fallen into disfavor in popular books and among many parenting researchers. Other well-respected researchers point out important instances where punishment can be beneficial if implemented appropriately together with positive reinforcement. In this chapter, we summarize the research on punishment, ranging from parental use of timeout to the clinical use of mild electric shocks to treat severe self-destructive behaviors that are otherwise resistant to change. We find that the bifurcation of research into causally informative studies of clinical child cases and correlational studies of more representative samples have prevented progress on how consistent mild punishment can enhance positive parenting techniques such as reasoning and negotiation, especially in children with oppositional defiance. We need better punishment research to help parents, because most of them will use some kind of punishment sometimes.

The begin by discussing the role of the American Psychological Association’s advocacy behavior:

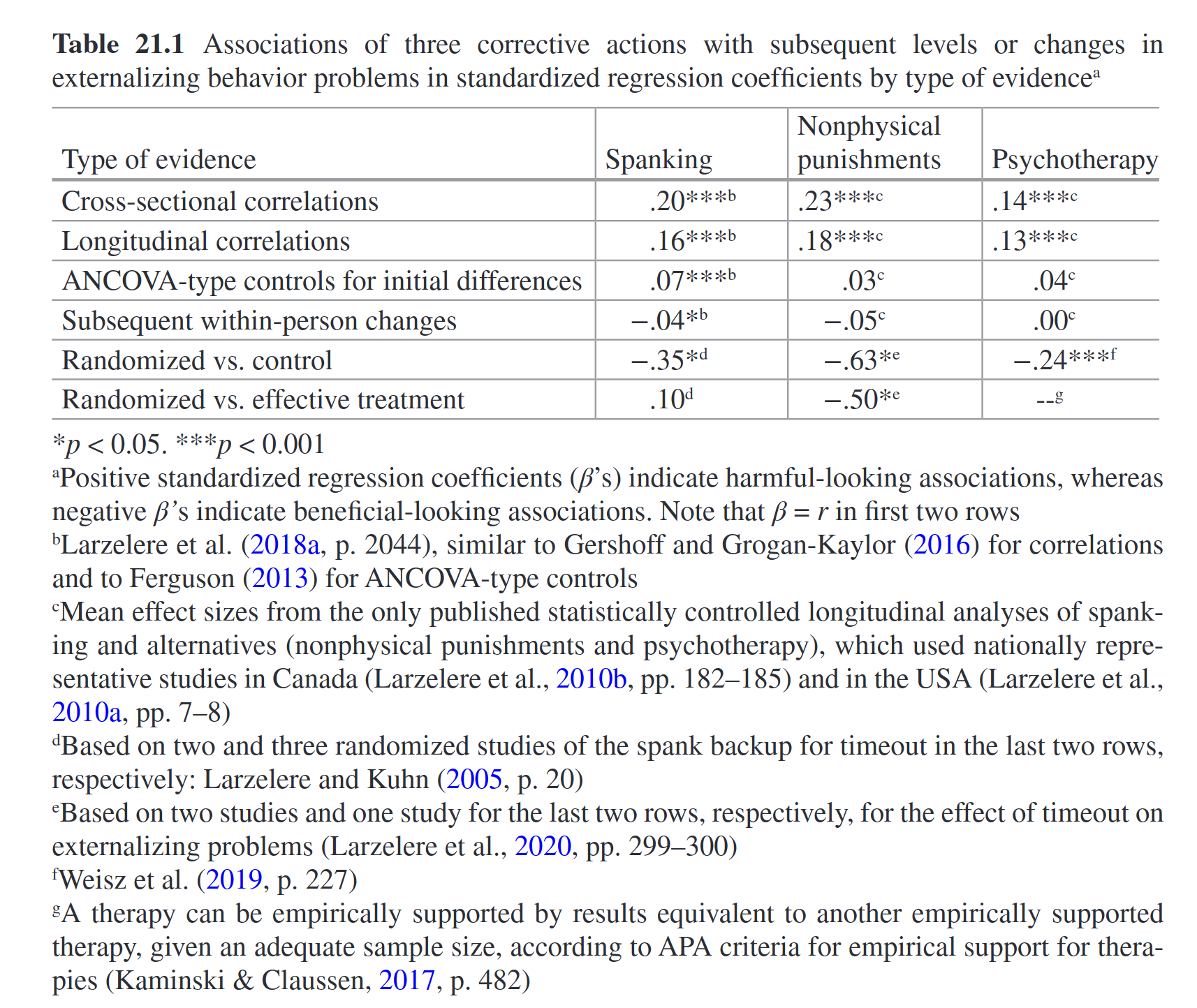

In 2018, the APA Task Force on Physical Punishment of Children recommended an APA resolution opposing all physical punishment, concluding that the “Research on physical punishment has met the requirements for causal conclusions” (Gershoff et al., 2018, p. 635). Although the Task Force cited five meta-analyses, they relied almost entirely on Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor’s (2016) evidence against physical punishment, which came exclusively from unadjusted correlations, mostly (55%) cross-sectional (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016, p. 455, 463–464). The Task Force ignored two stronger meta-analyses that went beyond correlations either by controlling statistically for preexisting differences (Ferguson, 2013) or by comparing effect sizes of physical punishment with those of alternative disciplinary tactics (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005). These other meta-analyses concluded that harmful effects of physical punishment were “trivial” (Ferguson, 2013) or limited to severe and predominant use of physical punishment (Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005).

After this, they performed their own literature review:

So in the weak designs (cross-section, longitudinal), we see that use of corporal punishment (spanking), non-physical punishment (e.g. time-out, grounding) both associate with later worse child behavior. However, the randomized trials find the opposite results, maybe even that spanking has a slight positive effect (but p < .05). They supply a few case studies:

In 1995, the parents of two young adults with severe developmental disabilities initiated a legal challenge against new legislation in Ontario that prohibited them from continuing to consent to electric-shock treatment for their two children (Gerhardt, 1996). That treatment had proven far more effective than anything else to prevent their children from harming themselves with extreme self-injurious behavior. Three other parents testified that the treatment had cured similar behaviors in their children, who had previously struck themselves from 30 to 124 times per minute, making them bloody and causing blindness in one of their eyes. One of the two suing parents testified that her son had banged his head up to 300 or 400 times per day before this treatment, unless fully restrained or medically sedated. All five parents testified that they had tried multiple treatments for many years before reluctantly trying aversive treatment, and all five testified that the treatment had benefited their children greatly.

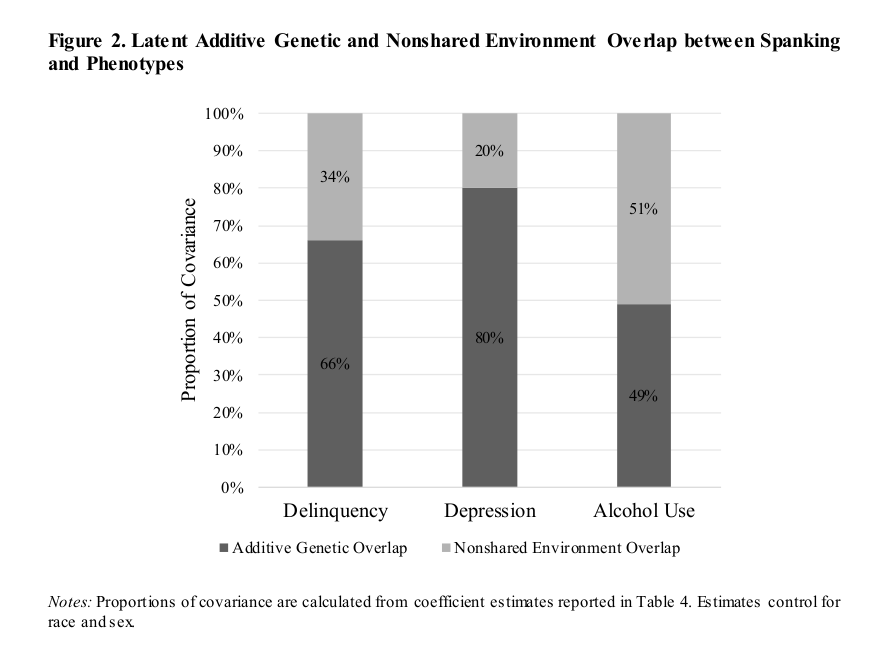

Do we have an alternative approach? I mentioned behavioral genetics above, so could we use family data to figure out the likely causality? There is at least one genetically informative study of spanking and ‘psychosocial outcomes’, and it does indeed find that 60-80% of the relationship between psychological variables and spanking is genetic in origin.

Beware that when variables show a genetic overlap (bivariate heritability), this is difficult to interpret because genetic causes can have behavioral mediators. The evidence here is consistent, I think, with spanking causing bad outcomes, but that this reflects shared genetics in who administers and receives the spanking. But certainly, the high joint heritability means that the cross-sectional data cannot be interpreted the ways most researchers do as merely reflecting parent-to-child causation.

I don’t know this literature well enough to say whether Larzelere and colleagues did their work properly, but I would not be surprised if the truth is as they say. There are many parenting methods one can use, and when children misbehave, some kind of punishment is in order. If the violation is severe enough, or the child stubborn enough, then maybe physical punishment is what is needed, with proper administration of course. Hanania and Collins thus appears to be on the right side of the evidence here, even if the evidence is not compelling. Certainly, there is no good evidence that occasional spanking causes severe behavioral problems in general, and little reason for it be to banned based on the weak evidence we have.