See prior post on national IQs and who you can’t cite.

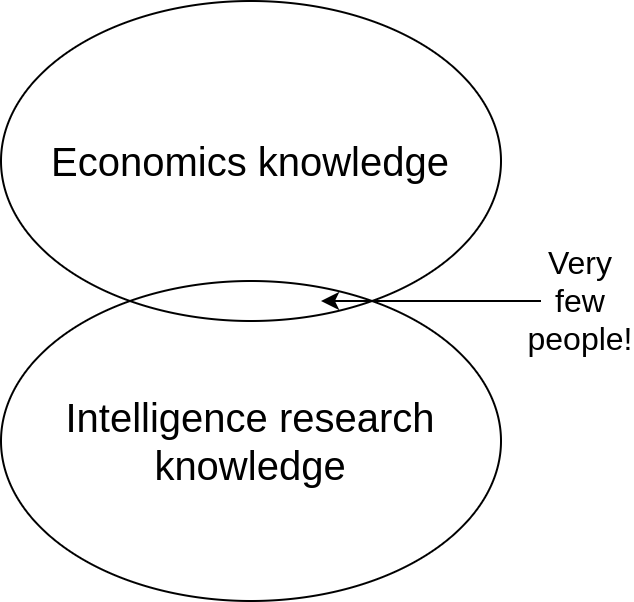

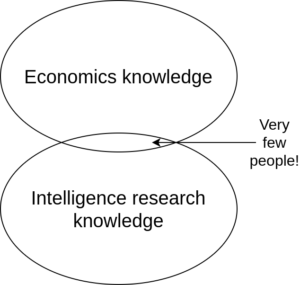

Economists and intelligence researchers don’t generally talk:

Test scores, on the other hand, offer direct measures of a variety of more-or-less specific abilities and, when the tests in question are well-constructed, objective, standardized tests, they are fairly precise measures that can be kept quite constant, over time and across space. Test experts know this; they also know a great deal about at least some of the abilities tests measure best but, because they are usually psychologists or educators and not economists, they tend to be preoccupied with their own non- economic questions, questions about why scores change and about the implications of such changes for individual development and for actions and policies intended to foster it. They do not usually know or care much about economists’ questions, and are not likely to notice when the abilities they measure directly are the same as those economists measure indirectly. Economists are not likely to notice either, because they are generally unfamiliar with the range and quality of available psychometric data and of its potential utility.

When was this written? In 1983 in this forgotten but interesting paper:

-

Lerner, B. (1983). Test scores as measures of human capital and forecasting tools. The Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies, 8(2), 131.

Various people have written about human capital at length mixing the findings from economics and intelligence research. Here follows a brief collection of key research.

-

Hanushek, E. A., & Kim, D. (1995). Schooling, labor force quality, and economic growth (No. w5399). National bureau of economic research.

Human capital is almost always identified as a crucial ingredient for growing economies, but empirical investigations of cross-national growth have done little to clarify the dimensions of relevant human capital or any implications for policy. This paper concentrates on the importance of labor force quality, measured by cognitive skills in mathematics and science. By linking international test scores across countries, a direct measure of quality is developed, and this proves to have a strong and robust influence on growth. One standard deviation in measured cognitive skills translates into one percent difference in average annual real growth rates—an effect much stronger than changes in average years of schooling, the more standard quantity measure of labor force skills. Further, the estimated growth effects of improved labor force quality are very robust to the precise specification of the regressions. The use of measures of quality significantly improves the predictions of growth rates, particularly at the high and low ends of the distribution. The importance of quality implies a policy dilemma, because production function estimates indicate that simple resource approaches to improving cognitive skills appear generally ineffective.

I think this is perhaps the first typical growth regression study with achievement test scores, though not IQs yet. They use data from before PISA was a thing, from IEA’s old surveys.

-

Lee, D. W., & Lee, T. H. (1995). Human capital and economic growth tests based on the international evaluation of educational achievement. Economics Letters, 47(2), 219-225.

Using the secondary school science achievement scores obtained by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, this paper provides more direct tests than others on the effect of human capital on economic growth, bearing important implications for theory and policy.

Like the above, but first formally published study, above is a working paper. Notable in that it actually cites Lerner’s pioneering paper, though it doesn’t show up on Google Scholar because it cited a book chapter reprint…

-

Hanushek, E. A., & Kimko, D. D. (2000). Schooling, labor-force quality, and the growth of nations. American economic review, 90(5), 1184-1208.

Direct measures of labor-force quality from international mathematics and science test scores are strongly related to growth. Indirect specification tests are generally consistent with a causal link: direct spending on schools is unrelated to student performance differences; the estimated growth effects of improved labor-force quality hold when East Asian countries are excluded; and, finally, home-country quality differences of immigrants are directly related to U.S. earnings if the immigrants are educated in their own country but not in the United States. The last estimates of micro productivity effects, however, introduce uncertainty about the magnitude of the growth effects.

A follow up on the above.

-

Weede, E., & Kämpf, S. (2002). The impact of intelligence and institutional improvements on economic growth. Kyklos, 55(3), 361-380.

Standard indicators of human capital endowment — like literacy, school enrollment ratios or years of schooling — suffer from a number of defects. They are crude. Mostly, they refer to input rather than output measures of human capital formation. Occasionally, they produce implausible effects. They are not robustly significant determinants of growth. Here, they are replaced by average intelligence. This variable consistently outperforms the other human capital indicators in spite of suffering from severe defects of its own. The immediate impact of institutional improvements, i.e., more government tolerance of private enterprise or economic freedom, on growth it is in the same order of magnitude as intelligence effects are. The senior author is responsible for picking a ‘politically incorrect’ topic, i.e., analyzing the impact of IQ or average intelligence. The junior author has done the data compilation and the computations.

This paper uses the Richard Lynn national IQs (2002) in a typical economist regression study for economic growth. I think this is the first growth modeling paper with national IQs specifically and being forthright about the constructs involved.

- Jones, G., & Schneider, W. J. (2006). Intelligence, human capital, and economic growth: A Bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. Journal of economic growth, 11(1), 71-93.

Human capital plays an important role in the theory of economic growth, but it has been difficult to measure this abstract concept. We survey the psychological literature on cross-cultural IQ tests and conclude that intelligence tests provide one useful measure of human capital. Using a new database of national average IQ, we show that in growth regressions that include only robust control variables, IQ is statistically significant in 99.8% of these 1330 regressions, easily passing a Bayesian model-averaging robustness test. A 1 point increase in a nation’s average IQ is associated with a persistent 0.11% annual increase in GDP per capita.

Possibly the most important of these studies. Needs replication and expansion. I suggest to go further back in time using age heaping data. These are also available for subnational units.

-

Ram, R. (2007). IQ and economic growth: Further augmentation of Mankiw–Romer–Weil model. Economics Letters, 94(1), 7-11.

Solow’s growth model is further augmented to include IQ in addition to proxies for education and health. The estimates indicate that IQ variable greatly erodes the size and significance of education and health parameters and dominates even a measure of institutional quality.

Dominating institutional measures is surprising, since one would expect that institutional quality largely mediates the link between intelligence and [other good stuff]. Also because institutions is what normie economics talk about when they try to explain cross-national variation (e.g. Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth, Acemoglu et al 2005, >6000 citations!). Naturally, it is also something that supports semi-open borders since they imagine one can keep institutions the same while taking in a lot of 3rd worlders.

- Jones, G., & Schneider, W. J. (2010). IQ in the production function: Evidence from immigrant earnings. Economic Inquiry, 48(3), 743-755.

We show that a country’s average IQ score is a useful predictor of the wages that immigrants from that country earn in the United States, whether or not one adjusts for immigrant education. Just as in numerous microeconomic studies, 1 IQ point predicts 1% higher wages, suggesting that IQ tests capture an important difference in cross‐country worker productivity. In a cross‐country development accounting exercise, about one‐sixth of the global inequality in log income can be explained by the effect of large, persistent differences in national average IQ on the private marginal product of labor. This suggests that cognitive skills matter more for groups than for individuals. (JEL J24, J61, O47)

Notable for being one of the first studies to use home national IQ for immigration outcomes. I already reviewed all of these studies in this post. Unfortunately, mainstreamers only did 2 papers (in 2010), and the other 12 are all mine.

-

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2011). The economics of international differences in educational achievement. In Handbook of the Economics of Education (Vol. 3, pp. 89-200). Elsevier.

An emerging economic literature over the past decade has made use of international tests of educational achievement to analyze the determinants and impacts of cognitive skills. The cross-country comparative approach provides a number of unique advantages over national studies: It can exploit institutional variation that does not exist within countries; draw on much larger variation than usually available within any country; reveal whether any result is country-specific or more general; test whether effects are systematically heterogeneous in different settings; circumvent selection issues that plague within-country identification by using system-level aggregated measures; and uncover general-equilibrium effects that often elude studies in a single country. The advantages come at the price of concerns about the limited number of country observations, the cross-sectional character of most available achievement data, and possible bias from unobserved country factors like culture.

This chapter reviews the economic literature on international differences in educational achievement, restricting itself to comparative analyses that are not possible within single countries and placing particular emphasis on studies trying to address key issues of empirical identification. While quantitative input measures show little impact, several measures of institutional structures and of the quality of the teaching force can account for significant portions of the large international differences in the level and equity of student achievement. Variations in skills measured by the international tests are in turn strongly related to individual labor-market outcomes and, perhaps more importantly, to cross-country variations in economic growth.

-

Jones, G. (2011). National IQ and national productivity: The hive mind across Asia. Asian Development Review, 28(1), 51-71.

A recent line of research demonstrates that cognitive skills – intelligence quotient scores, math skills, and the like – have only a modest influence on individual wages, but are strongly correlated with national outcomes. Is this largely due to human capital spillovers? This paper argues that the answer is yes. It presents four different channels through which intelligence may matter more for nations than for individuals: (i) intelligence is associated with patience and hence higher savings rates; (ii) intelligence causes cooperation; (iii) higher group intelligence opens the door to using fragile, high-value production technologies; and (iv) intelligence is associated with supporting market-oriented policies. Abundant evidence from across ADB member countries demonstrates that environmental improvements can raise cognitive skills.

-

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2012). Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. Journal of economic growth, 17(4), 267-321.

We develop a new metric for the distribution of educational achievement across countries that can further track the cognitive skill distribution within countries and over time. Cross-country growth regressions generate a close relationship between educational achievement and GDP growth that is remarkably stable across extensive sensitivity analyses of specification, time period, and country samples. In a series of now-common microeconometric approaches for addressing causality, we narrow the range of plausible interpretations of this strong cognitive skills-growth relationship. These alternative estimation approaches, including instrumental variables, difference-in-differences among immigrants on the U.S. labor market, and longitudinal analysis of changes in cognitive skills and in growth rates, leave the stylized fact of a strong impact of cognitive skills unchanged. Moreover, the results indicate that school policy can be an important instrument to spur growth. The shares of basic literates and high performers have independent relationships with growth, the latter being larger in poorer countries.

-

Meisenberg, G., & Lynn, R. (2012). Cognitive human capital and economic growth: Defining the causal paths. Journal of Social Political and Economic Studies, 38, 16-54.

This study examines two key issues about the role of cognitive human capital (also known as intelligence) for economic growth between 1975 and 2009: (1) the measures of cognitive human capital that are most relevant to the prediction of economic growth; and (2) the proximate mechanisms through which this form of human capital promotes economic growth. We find that cognitive ability, measured as IQ or school achievement, robustly predicts economic growth on a worldwide scale. These two measures can be averaged into a single measure of “intelligence.” In multivariate analyses that include a measure of cognitive ability, length of schooling is a poor predictor of economic growth. The growth-promoting effect of cognitive ability is mediated by multiple mechanisms, including lower fertility and greater technological competitiveness in developing countries, and increased domestic saving rate and reduced burden of infectious diseases in all countries. The main conclusion is that rising intelligence has been a major determinant of economic growth in the recent past.

-

Jones, G. (2012). Cognitive skill and technology diffusion: An empirical test. Economic systems, 36(3), 444-460.

Cognitive skills are robustly associated with good national economic performance. How much of this is due to high-skill countries doing a better job of absorbing total factor productivity from the world’s technology leader? Following Benhabib and Spiegel (Handbook of Economic Growth, 2005), who estimated the Nelson–Phelps technology diffusion model, I use the database of IQ tests assembled by Lynn and Vanhanen, 2002, Lynn and Vanhanen, 2006 and find a robust relationship between national average IQ and total factor productivity growth. Controlling for IQ, years of education is of modest statistical significance. If IQ gaps between countries persist and model parameters remain stable, TFP levels are forecasted to sharply diverge, creating a “twin peaks” result. After controlling for IQ, few other growth variables are statistically significant.

-

Christainsen, G. B. (2013). IQ and the wealth of nations: How much reverse causality?. Intelligence, 41(5), 688-698.

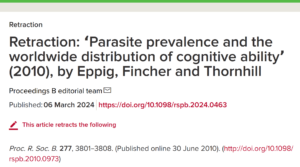

This paper uses data from 130 IQ test administrations worldwide and employs regression analysis to try to quantify the impact of living conditions on average IQ scores in nationally-representative samples. The study emphasizes the possible role of conditions at or near the test-takers’ time of birth. The paper finds that the impact of living conditions is of much smaller magnitude than is suggested by just looking at correlations between average IQ scores and socioeconomic indicators. After controlling for test-takers’ region of ancestry, the impact of parasitic diseases on average IQ is found to be statistically insignificant when test results from the Caribbean are included in the analysis. As far as IQ and the wealth of nations are concerned, causality thus appears to run mostly from the former to the latter. The test-takers’ region of ancestry dominates the regression results. While differences in average scores worldwide can thus be plausibly viewed as being influenced by genetic differences across world regions, it is also possible that score differences are influenced by regional differences in culture that are independent of genetic factors. Differences in average IQ across world regions may change in the years ahead insofar as the strength of Flynn effects may not be uniform, but some regional differences in average g levels seem likely to continue indefinitely.

-

Jones, G., & Potrafke, N. (2014). Human capital and national institutional quality: Are TIMSS, PISA, and national average IQ robust predictors?. Intelligence, 46, 148-155.

Is human capital a robust predictor of good institutions? Using a new institutional quality measure, the International Property Rights Index (IPRI), we find that cognitive skill measures are significant, robust, and large in magnitude. We use two databases of cognitive skills: estimates of national average IQ from Lynn and Vanhanen (2012a) and estimates of cognitive ability based on Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) scores estimated by Rindermann, Sailer, and Thompson (2009). The Rindermann cognitive ability scores estimate mean performance as well as performance at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the national population. National average IQ and the 95th percentile of cognitive ability are both robust predictors of overall institutional quality controlling for legal system, GDP per capita, geography dummies, and years of total schooling. Some possible microfoundations of this relationship are discussed.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2015). The knowledge capital of nations: Education and the economics of growth. MIT press.

Book length review from their perspective. Have not read this but I should.

-

Jones, G. (2015). Hive mind: How your nation’s IQ matters so much more than your own. Stanford University Press.

Another book length review from an economist perspective. This one is suitable for non-researchers, experts won’t learn much. See review here.

-

Rindermann, H. (2018). Cognitive capitalism: Human capital and the wellbeing of nations. Cambridge University Press.

A long book that reviews tons of stuff from a psychologist perspective, but it is very broad in coverage.

- World Bank: Harry A. Patrinos & Noam Angrist. August 12, 2019. Harmonized learning outcomes: transforming learning assessment data into national education policy reforms.

In the most mainstream move yet, the World Bank has put out their own averaging of test scores. They are still too cowardly to label it correct (intelligence), but they call it “harmonized test scores” and “learning outcomes” (previously “education quality”, thus assuming that schooling causes the score gaps, what lies!). OK, whatever, we will take it. They even produce verboten maps like this:

They have a project with a website of their dataset.

- Meisenberg, G. (2020). Editorial: Human Capital and the Wealth of Nations. Mankind Quarterly, 60(4), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.2020.60.4.1

A strange editorial-research paper, but very nice brief review.

- Christainsen, G. B. (2020). Rushton, Jensen, and the Wealth of Nations: Biogeography and Public Policy as Determinants of Economic Growth. MANKIND QUARTERLY, 60(4), 458-486.

This paper offers a review of some of the empirical literature on economic growth and discusses its recent evolution in light of developments in intelligence research and genomics. The paper also undertakes the first regression analysis of economic growth to use the most up-to-date version (VI.3.2) of David Becker’s data set of international IQ scores. The analysis concerns the growth of 94 countries from 1995-2016. The new regression analysis replicates the results of Jones and Schneider (2006) in finding IQ to have a robust impact on economic growth. Political and economic institutions are represented in the regressions via a country’s “degree of capitalism” (aka “economic freedom”), which is found to have an impact that is positive and statistically significant. A change from communism to a market economy does much to increase growth, but the paper finds diminishing returns to free markets. Countries whose people are mostly of sub-Saharan African descent have low average IQ scores, but the paper finds that other factors also have lessened economic growth not only in Africa, but in Haiti and Jamaica as well. Rushton and Jensen (2005, 2010) put forth the hypothesis that average IQ differences across ethnic groups are 50% due to genetic differences, and 50% due to differences in natural and social environments. Applied to international IQ scores, the paper finds the hypothesis to be very reasonable.

Christainsen is working to integrate the fields better and replicate findings. Stay tuned for more upcoming work by him.

So the research seems to be picking up pace in recent years, no doubt due to massive availability of open data every few years from PISA, TIMSS, PIAAC and so on, multiple ready-made national datasets. The internet also makes it easier to talk to people outside one’s expertise.