It’s all based on this article, which received ample media attention:

- Gignac, G. E., & Zajenkowski, M. (2019). People tend to overestimate their romantic partner’s intelligence even more than their own. Intelligence, 73, 41-51.

People can estimate their own and their romantic partner’s intelligence (IQ) with some level of accuracy, which may facilitate the observation of assortative mating for IQ. However, the degree to which people may overestimate their own (IQ), as well as overestimate their romantic partner’s IQ, is less well established. In the current study, we investigated four outstanding issues in this area. First, in a sample of 218 couples, we examined the degree to which people overestimate their own and their partner’s IQ, on the basis of comparisons between self-estimated intelligence (SEI) and objectively measured IQ (Advanced Progressive Matrices). Secondly, we evaluated whether assortative mating for intelligence was driven principally by women (the males-compete/females choose model of sexual selection) or both women and men (the mutual mate model of sexual selection). Thirdly, we tested the hypothesis that assortative mating for intelligence may occur for both SEI and objective IQ. Finally, the possibility that degree of intellectual compatibility may relate positively to relationship satisfaction was examined. We found that people overestimated their own IQ (women and men ≈ 30 IQ points) and their partner’s IQ (women = 38 IQ points; men = 36 IQ points). Furthermore, both women and men predicted their partner’s IQ with some degree of accuracy (women: r = 0.30; men: r = 0.19). However, the numerical difference in the correlations was not found to be significant statistically. Finally, the degree of intellectual compatibility (objectively and subjectively assessed) failed to correlate significantly with relationship satisfaction for both sexes. It would appear that women and men participate in the process of mate selection, with respect to evaluating IQ, consistent with the mutual mate model of sexual selection. However, the personal benefits of intellectual compatibility seem less obvious.

But Emil, the claim is right there in the abstract! Yes, but it is pretty dumb, based on a weird transformation. Look in the methods:

8.2.1. Subjectively assessed intelligence Participants assessed their own and their partner’s intelligence on a 1–25 point rating scale. Five groups of five columns were labelled as very low, low, average, high or very high, respectively (see Fig. 1). Participants’ SAI was indexed with the marked column counting from the first to the left; thus the score ranged from 1 to 25 (see Zajenkowski et al., 2016 for more details). Prior to providing a response to the scale, the following instruction was presented:

People differ with respect to their intelligence and can have a low, average or high level. Using the following scale, please indicate where you can be placed compared to other people. Please mark an X in the appropriate box corresponding to your level of intelligence.

For partner’s IQ estimation, the last two sentences of the instructions were:

Using the following scale, please indicate where your partner can be placed compared to other people. Please mark an X in the appropriate box corresponding to your partner’s level of intelligence.

In order to place the 25-point scale SAI scores onto a scale more comparable to a conventional IQ score (i.e., M = 100; SD = 15), we transformed the scores such that values of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5… 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 were recoded to 40, 45, 50, 55, 60… 140, 145, 150, 155, 160. As the transformation was entirely linear, the results derived from the raw scale SAI scores and the recoded scale SAI scores were the same.

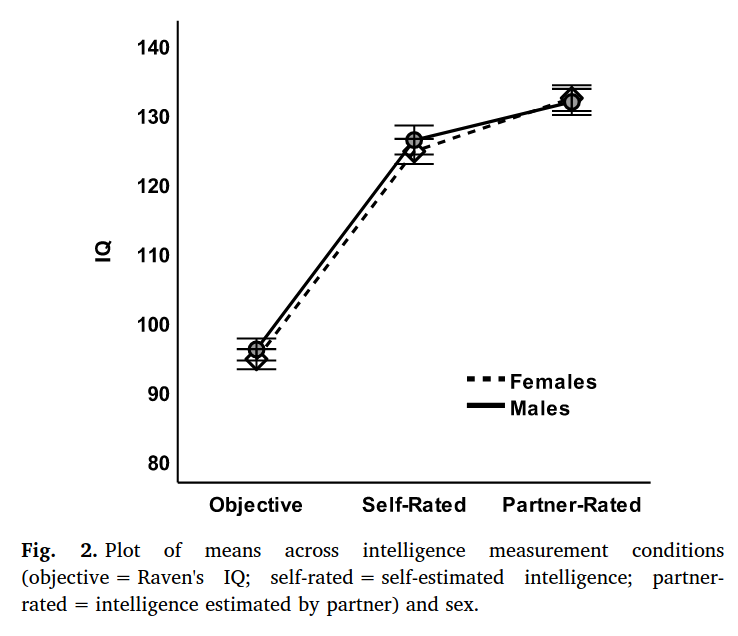

So, giving people an arbitrary 1-25 scale and then assumed each point corresponds to 5 IQ and then assuming subjects understood this, then one can compare their Raven’s IQs to the estimated IQs, and of course they are overestimated. Using this transformation, the overestimation comes out to 30 IQ or so, but it’s entirely a result of this scaling. Looks like this:

And if you plot the results:

So really, what this study found is that people put themselves and their partners about in the middle of the “high” bracket on the arbitrary scale above. This is too high, but people do not generally imagine themselves to be in the top 2-5%’s of the intelligence distribution on average.

People do often overestimate themselves, but it’s not that extreme. When you give a bunch of Twitter people a ratio scale question like “The previous page featured 25 questions testing your knowledge. How many correct answers do you think you gave?” people were too high on average by… they were actually too low by about 1 question!

People did estimate themselves to be on average 68th centile, which may be accurate, as this is a self-selected sample. If we assume the sample is of average intelligence (100), this corresponds to about 107 IQ, hardly a grievous overestimation. A typical better-than-average study finds an overestimation of:

The better-than-average-effect (BTAE) is the tendency for people to perceive their abilities, attributes, and personality traits as superior compared with their average peer. This article offers a comprehensive review of the BTAE and the first quantitative synthesis of the BTAE literature. We define the effect, differentiate it from related phenomena, and describe relevant methodological approaches, theories, and psychological mechanisms. Next, we present a comprehensive meta-analysis of BTAE studies, including data from 124 published articles, 291 independent samples, and more than 950,000 participants. Results indicated that the BTAE is robust across studies (dz = 0.78, 95% CI [0.71, 0.84]), with little evidence of publication bias. Further, moderation tests suggested that the BTAE is larger in the case of personality traits than abilities, positive as opposed to negative dimensions, and in studies that (a) use the direct rather than the indirect method, (b) involve many rather than few dimensions, (c) sample European Americans rather than East-Asians (especially for individualistic traits), and (d) counterbalance self and average peer judgments. Finally, the BTAE is moderately associated with self-esteem (r = .34) and life satisfaction (r = .33). Results from selection model analyses clarify areas of the BTAE literature in which publication bias may be of elevated concern. Discussion highlights theoretical and empirical implications.

d 0.78 is about 12 IQ. That’s for people themselves. In the study above, we saw that people overestimated their romantic partners a bit more, so maybe 15 IQ. Half the 30 claimed. That’s a big difference. This is assuming no bias (publication bias/p-hacking) in the meta-analysis, which is almost guaranteed.

It’s interesting to note the positive associations between self-overestimation and positive psychological outcomes. Seems like narcissism is adaptive. Fake it till you make it, and often you will make it, so you no longer have to fake it.