Back in 2015 at ISIR, a researcher gave a presentation about mental illness and intelligence, reporting it was elevated at high intelligence levels, along with all kinds of other issues. This was later published as a paper in 2018.

- Karpinski, R. I., Kolb, A. M. K., Tetreault, N. A., & Borowski, T. B. (2018). High intelligence: A risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities. Intelligence, 66, 8-23.

High intelligence is touted as being predictive of positive outcomes including educational success and income level. However, little is known about the difficulties experienced among this population. Specifically, those with a high intellectual capacity (hyper brain) possess overexcitabilities in various domains that may predispose them to certain psychological disorders as well as physiological conditions involving elevated sensory, and altered immune and inflammatory responses (hyper body). The present study surveyed members of American Mensa, Ltd. (n = 3715) in order to explore psychoneuroimmunological (PNI) processes among those at or above the 98th percentile of intelligence. Participants were asked to self-report prevalence of both diagnosed and/or suspected mood and anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and physiological diseases that include environmental and food allergies, asthma, and autoimmune disease. High statistical significance and a remarkably high relative risk ratio of diagnoses for all examined conditions were confirmed among the Mensa group 2015 data when compared to the national average statistics. This implicates high IQ as being a potential risk factor for affective disorders, ADHD, ASD, and for increased incidence of disease related to immune dysregulation. Preliminary findings strongly support a hyper brain/hyper body association which may have substantial individual and societal implications and warrants further investigation to best identify and serve this at-risk population.

Now at ISIR in Vienna in 2022, we get this talk:

High intelligence is associated with mental health problems in a sample of intellectually gifted Europeans

Mr. Jonathan Fries 1 , Dr. Tanja G. Baudson2,3,4 , Dr. Kristof Kovacs 5 , Dr. Jakob Pietschnig1

SP

1 Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna,

Austria

2 HS Fresenius Heidelberg University of Applied Sciences, Heidelberg, Germany

3 Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education (IGDORE)

4 MENSA in Deutschland gGmbH, Germany

5 Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, HungaryBackground: High intelligence is a well-known predictor of favorable health outcomes and longer lifespans. However, recent evidence suggests that the proposed linear relationship between health and cognitive ability might not extend to the upmost end of the intelligence spectrum, indicating that intellectually gifted individuals exhibit high prevalences in an array of specific physical and mental health conditions, so-called overexcitabilities. Presently, only few targeted investigations of this research question have been carried out, and none outside the USA. Here, our objective was to replicate and extend previous accounts to numerous uninvestigated overexcitabilities in a sample of intellectually gifted Europeans.

Methods: We conducted a preregistered survey among members of MENSA, the world’s largest society of individuals scoring in the highest two percent of the intelligence distribution. In all, 615 (307 female) members of the chapters from Austria, Germany, Hungary, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom participated. Results: Compared to reference populations, the intellectually gifted sample showed considerably elevated rates of several conditions, such as autism spectrum disorders (risk ratio = 2.25), chronic fatigue syndrome (RR = 5.69), depression (RR = 4.38), generalized anxiety (RR = 3.82), or irritable bowel syndrome (RR = 3.76). Previously reported conditions such as asthma, allergies, or autoimmune diseases were within the general population range.

Discussion: We demonstrate that gifted individuals face specific health challenges com- pared to the general population. Contrary to previous work, mental health was markedly more affected than physical health. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon currently remains speculative, because our investigation yielded only limited evidence for the previously endorsed psychoneuroimmunological explanation. Our results partially contrast earlier findings and call into question whether “overexcitability” is a useful term to describe health issues experienced by intellectually gifted individuals.

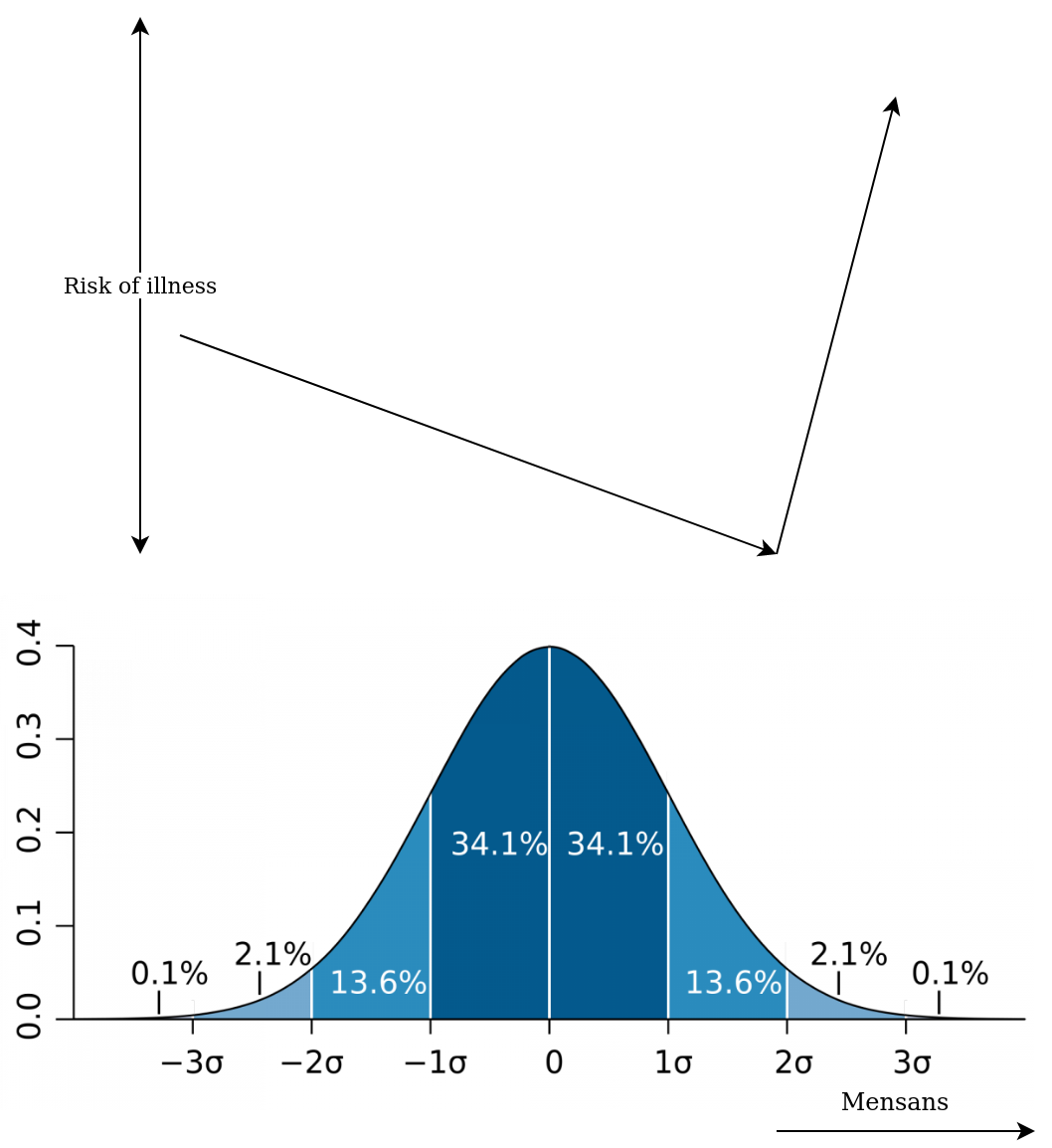

It’s a textbook example of sampling bias. The samples rely on Mensa samples. For this study to work, Mensans have to be representative of smart people in general, or at least, not be a biased sample for the things examined. But everybody knows Mensans are dorks and this is a club for underachievers. For some amusing quantitative evidence, check out the Reddit subreddit overlap tool. The strongest overlap for being in Mensa is also being in introverted personality subreddits, with a 60x+ rate. Now, low achievement for one’s intelligence can be explained by only a few things: bad work ethic, physical disability, and mental illness. These often go together (genetic fitness factor). Mensans are below average achievers for their intelligence level, and this has a lot to do with their other traits. Obviously, then, studying Mensa people and finding that they have a high rate of various issues compared to a normal population does not tell you that intelligence is associated with these problems, but rather that you have strong sampling bias. The normal way to study intelligence’s relationship to health, physical as well as mental, is to rely on large population surveys. These invariably show positive correlations, I covered the mental health and intelligence relationship in depth before, and the physical relationship was covered in a special issue about cognitive epidemiology back in 2009, but there’s newer research too. Thus, one has to either claim a very strong non-monotonic relationship for intelligence and these outcomes, such that 130+ Mensans can be at elevated risk, OR one has to conclude there is a strong sampling bias. Let’s illustrate what the Mensa people implied model looks like:

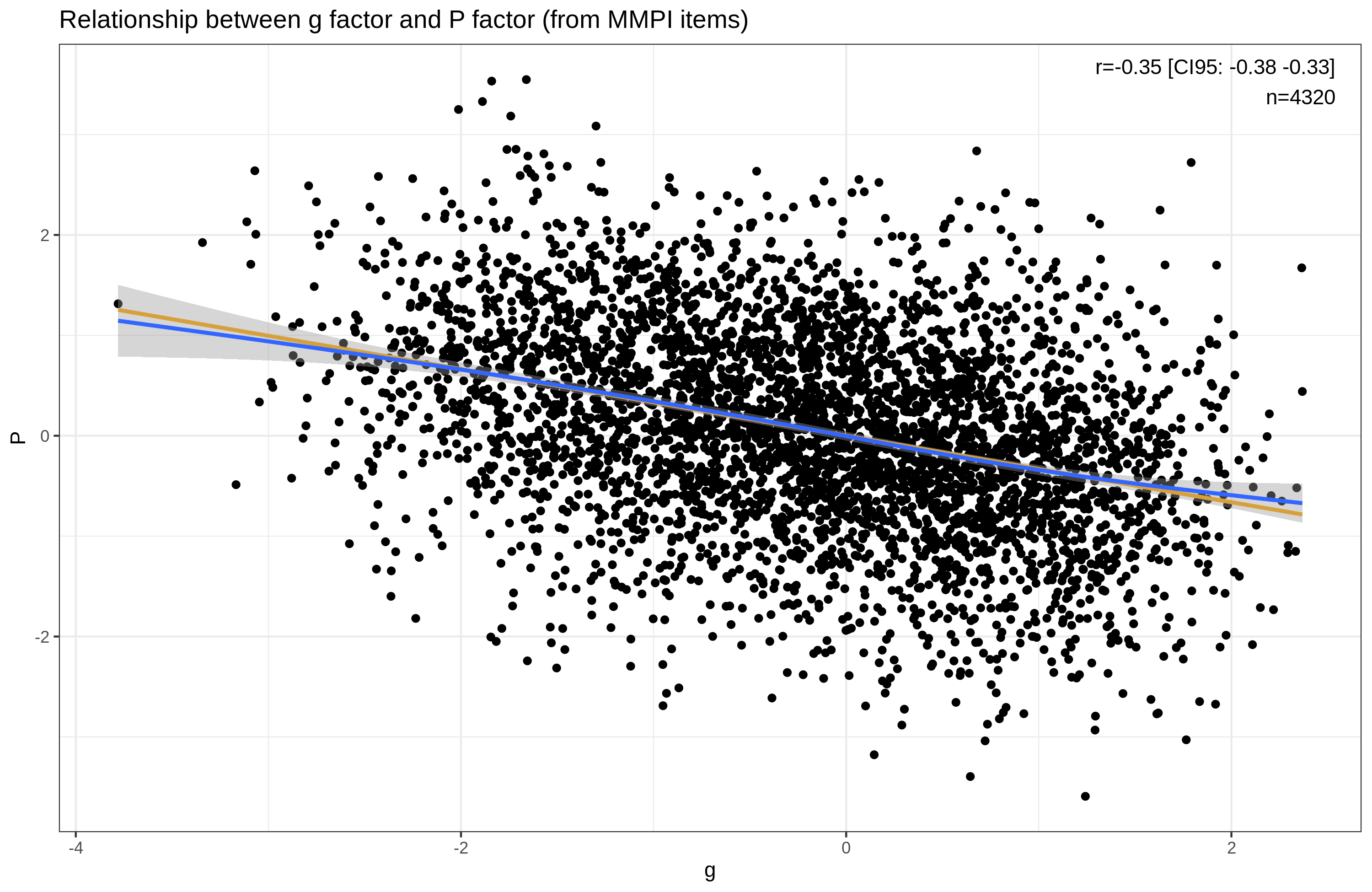

Here’s a plot of how a general score of mental health from the MMPI-2 looks like together with intelligence:

This is from our study of US army Vietnam veterans. (This plot is in the supplementary materials.) The blue line shows the non-linear fit. It doesn’t deviate from the linear fit shown in orange. Here’s plots from other studies that I covered previously:

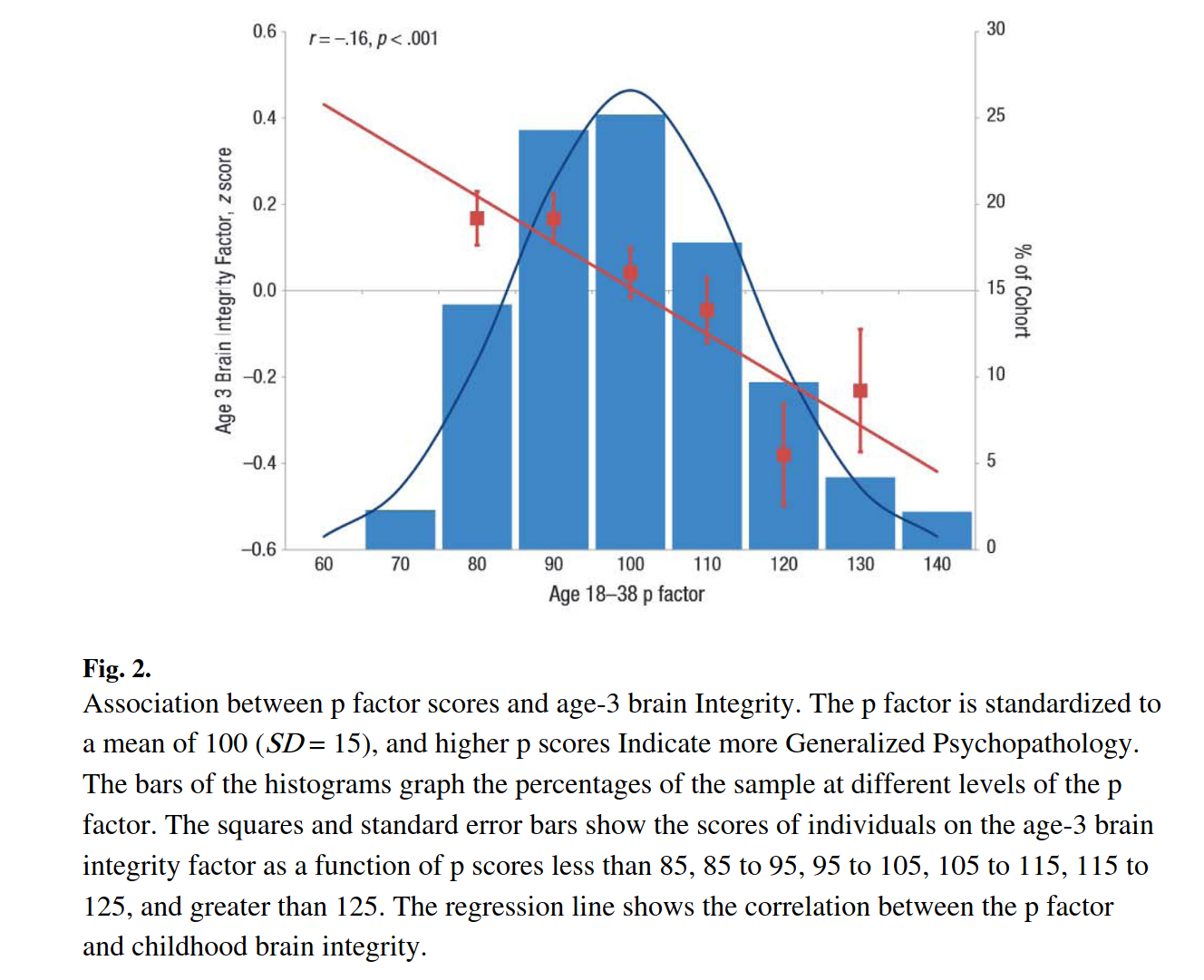

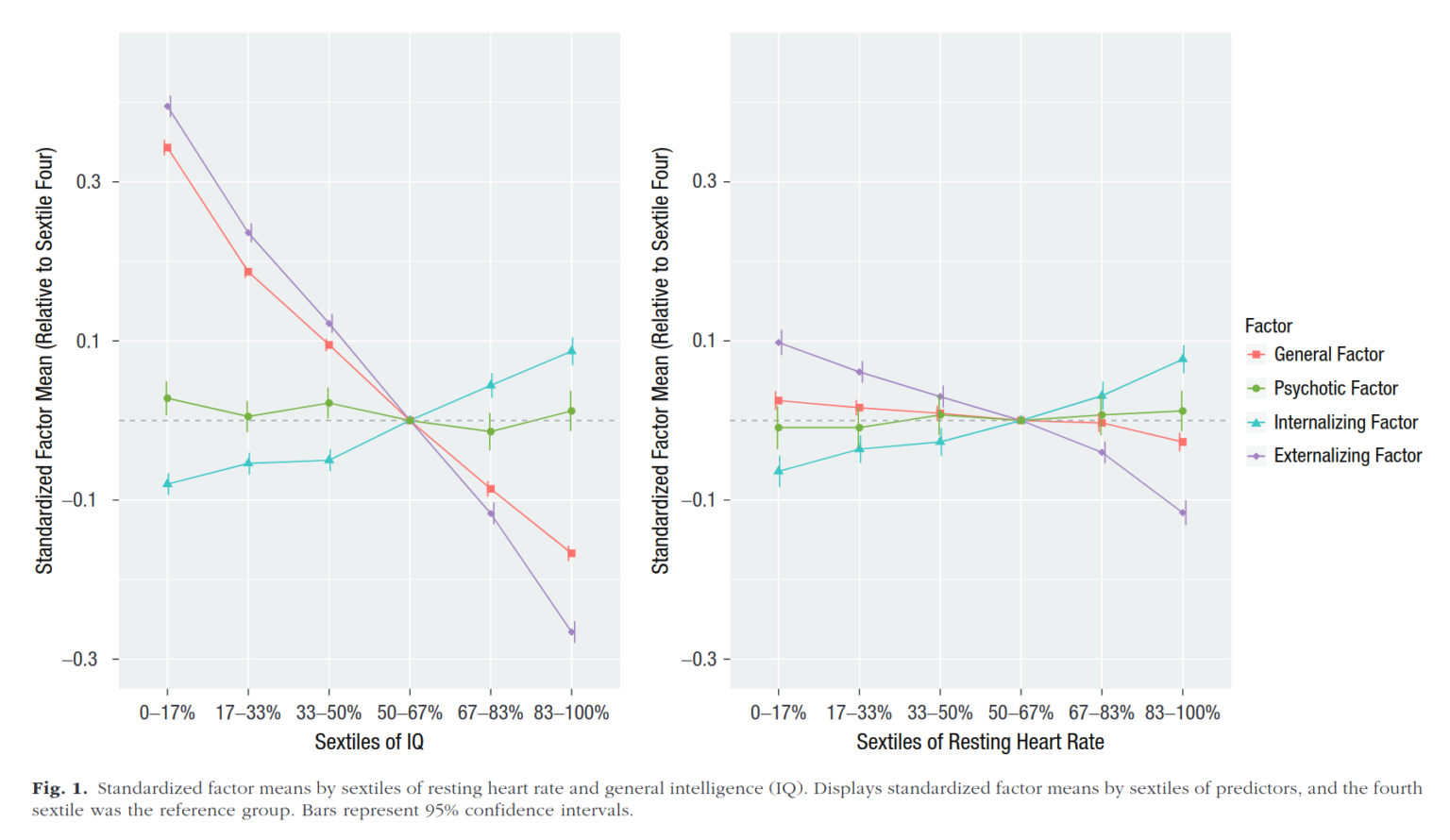

There is a slight uptick at 130 vs. 120, but the error bars are overlapping, so don’t make anything of this. Here’s a third:

Again, it is very close to linear for the observed range. The Mensa study people have to claim that these large general studies do not have sufficient range of intelligence, i.e., that the non-monotonic pattern can only be seen 130+ or maybe further out. It’s very unlikely.

There are a few proper high IQ samples where one could study this: SMPY and Terman. One could show the self-selection by asking their members whether they belong or previously belonged to a high IQ society like Mensa. My contention is that this will be predicted by bad health especially mental. I discussed the issue with Camilla Benbow, of SMPY fame. She said they are doing a new survey of SMPY soon, and it’s possible they will include this question, so that we can test this hypothesis. I will send her this blogpost, and we will see what happens!

In fact, this Mensa fallacy is not new at all. Gwern posted about it some years ago in a note on his SMPY literature review post (he was also at ISIR 2015):

An example of the ‘Mensa fallacy’—using a pathologically self-selected self-diagnosed sample—would be Karpinski et al 2018, “High intelligence: A risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities”, which takes Mensa survey results at face-value while ignoring the fact that Mensa has attracted losers since its founding (a fact that I know was pointed out to the authors well before publication, and which they defend merely by saying that self-report data is common in many other areas while ignoring all contradictory evidence, which they pass over in silence).

The results are a priori unlikely as all population samples show that good things increase (eg. Brown et al 2021), and dysfunctionality & mental illness rates drop steeply with increasing IQ definitely at least to the top decile (often the top percentile) with no quadratic or other curve observable indicating asymptotes or impending reversals; these results are so large and well known that Karpinski et al cannot doubt them, and so they attempt to ‘save the appearances’ with ad hoc invocations of nonlinear thresholds at high intelligence, while still relying on the relatively low IQ threshold of Mensa membership. Their results are so absurd as to discredit any attempt to claim that a Mensa sample can tell us anything at all about high intelligence, as (with the exception of the modest allergies finding) they are completely inconsistent with genetic & phenotypic correlations, almost impossible to reconcile with the universal life-expectancy/SES/education/IQ/wealth/mental-health correlations observed everywhere in psychology/sociology/medicine, and non-self-selected high-IQ samples (whether Terman, SMPY, FLS, Munich Longitudinal Study, SET, HCES, Scottish survey, Scandinavian population registry-based, UKBB etc)—including a self-reported Asperger’s relative risk of 223!It’s unclear how these are even arithmetically reconcilable with the population estimates, as such large risk increases ought to push the averages way up at the top decile or percentiles, overwhelming the modest lower risks for non-Mensa-level individuals. Further, if any of the relative risks were true, higher intelligence would be one of the strongest risk factors ever discovered for illness, far exceeding the effects of minor things like smoking. If such relative risks were true of Mensans, who are merely ~+2.3SD (being generous & taking their 1% criterion at face-value), then the RRs of groups like SMPY, MIT, Nobelists, or Fields Medalists, who are 3–6SD, would be off the charts, and it would be difficult to so much as run a SMPY summer-camp without dealing with multiple suicide attempts or psychotic breaks, or find a single child who seemed at all socially-well-adjusted, or an eminent scientist who had not been institutionalized, or… Of course, this is not the case. No reported statistics from SMPY or other high-IQ samples not suffering from self-selection into exaggerated self-diagnoses agree with this, and researchers & journalists who interact with SMPYers and similar high-IQ cohorts fail to mention that the entire cohort is nuttier than a Snickers bar, and often mention that the members defy stereotype by seeming quite healthy, well-adjusted, and happy. (The implications continue to go beyond that—considering just genetics, such pathology would force stabilizing selection, which we do not observe.)

So all Karpinski et al 2018 has to offer is a cautionary warning about GIGO: Mensa members are either remarkably selected for pathologies, or are not responding honestly (perhaps due to the trendiness of self-diagnosing autism as an excuse for failure).

Yet here we are. In fact, these Mensa sample studies go back a long time. I looked around in the literature and studies of Mensans have been done since at least 1960s:

- Fogel, M. L. (1968). Mensa society. American Psychologist, 23(6), 457.

This column discusses Mensa. The author would like qualified research workers, such as psychologists or graduate students working on theses or dissertations, who are in need of a high-IQ group to consider studying Mensa. Mensa is a ready-made population of high-intelligence subjects, representing all levels and fields of endeavor, who would be willing to participate in psychological studies and opinion surveys. The only qualification for membership in Mensa is a score on an acceptable intelligence test higher than that of 98% of the general population. At present there are 17,000 active members, of whom 12,000 are American.

- Taft, R. (1971). A note on the characteristics of the members of Mensa, a potential subject pool. The Journal of Social Psychology, 83(1), 107-111.

One third of the respondents did not live a t home with two parents during their childhood (up to the age of 16 years). Of these respondents, approximately a third came from homes broken by a separation or divorce between their parents: i.e., 12 percent of the entire sample. A further 12 percent of the homes were not intact because of the death of one or both of the parents. This suggests much less domestic stability than is the normal in Australian middle-class homes, especially when it is noted that the respondents tended to be firstborn (see below). As further evidence of the instability of their homes, one third of the respondents described their homes as unhappy when they were children. This is double the figure found by the author in an unpublished study of 254 mature persons who were attending adult education summer courses in Western Australia. It is also double the figure found for Australian university students.

…

Twenty percent of the respondents indicated that they had suffered from a serious physical disability extending over a long period of time. Nearly 40 percent of these disabilities were respiratory allergies (asthma and hay fever), and 20 percent were visual defects. However, 89 percent of the respondents described their general health throughout their life as “quite healthy” or “very healthy.” O n the whole the males were more healthy and had fewer serious disabilities than the females. Thirty percent of the males and 32 percent of the females reported that they had had serious emotional conflicts that have interferred with their lives or have led to illnesses requiring medical attention. This compares with 18 percent of males and 38 percent of females found for a general Australian population ( 5 ) . Thus the Mensa males are high on neurotic manifestations, while the females are about normal.

…

It is not always possible to infer whether the characteristics found for the Mensa members are related to their high intelligence, or to the fact that they represent a group of persons who have voluntarily joined this exclusive group. As a third possibility the special characteristics could be due to a combination both these factors; this seems to be the most likely explanation, since some of the characteristics, such as the highly educated backgrounds are associated with high intelligence, and some, such as being exhibitionistic and dissatisfied, probably relate more to their willingness to join the Mensa organization

Given this rather obvious problem, it is amazing to see this kind of study being done multiple times. Then again, the Karpinski study already has 160 citations since 2018 and was widely featured around the internet (> 11k social media mentions), so there is surely a big demand for studies showing this fake relationship. As such, we can expect academics to keep producing these studies. Science as usual.

Addendum

After writing this post, a colleague pointed out that there is a preprint also pointing out this issue. It was given by a talk at ISIR 2022 too, but since I didn’t see these talks (on account of being barred from the conference!), I didn’t know about this preprint. Here it is:

- Williams, C. M., Peyre, H., Labouret, G., Fassaya, J., Garcia, A. G., Gauvrit, N., & Ramus, F. (2022). High Intelligence is not a Risk Factor for Mental Health Disorders. medRxiv.

Objective Studies reporting that highly intelligent individuals have more mental health disorders often have sampling bias, no or inadequate control group, or insufficient sample size. We addressed these caveats by examining the difference in the prevalence of mental health disorders between individuals with high and average general intelligence (g-factor) in the UK Biobank.

Methods Participants with general intelligence (g-factor) scores standardized relative to the same-age UK population, were divided into 2 groups: a high g-factor group (g-factor 2 SD above the UK mean; N=16,137) and an average g-factor group (g-factor within 2 SD of the UK mean; N=236,273). Using self-report questionnaires and medical diagnoses, we examined group differences in prevalence across 32 phenotypes, including mental health disorders, trauma, allergies, and other traits.

Results High and average g-factor groups differed across 15/32 phenotypes and did not depend on sex and/or age. Individuals with high g-factors had less general anxiety (OR=0.69) and PTSD (OR=0.67), were less neurotic (β=-0.12), less socially isolated (OR=0.85), and were less likely to have experienced childhood stressors and abuse, adulthood stressors, or catastrophic trauma (OR=0.69-0.90). They did not differ in any other mental health disorder or trait. However, they generally had more allergies (e.g., eczema; OR=1.13-1.33).

Conclusions The present study provides robust evidence that highly intelligent individuals have no more mental health disorders than the average population. High intelligence even appears as a protective factor for general anxiety and PTSD.

Question Are high IQ individuals at increased risk of mental health disorders?

Findings In the UK Biobank (N ≃ 7,266 – 252,249), highly intelligent individuals (2SD above the population mean) were less likely to suffer from general anxiety and PTSD, and no more likely to have depression, social anxiety, a drug use disorder, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Meaning Contrary to popular belief, high intelligence is not a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and even serves as a protective factor for general anxiety and PTSD.

So my conclusions hold just as well in the UK Biobank too. Nothing too surprising. The finding of allergies, I question because diagnoses and self-reported diagnoses are affected by individuals seeking out diagnoses. I thinking is that smarter people are more inclined to figure out sensitivities they might or might not have to food and get an official diagnosis, or a self-diagnosis for these. The only way around this confound is to use a physician check-out and test for all the relevant traits for each subject. Such datasets are rare, but exist for e.g. draftees who undergo mandatory physical examination.