Let me tell you a story about science. (Deep breath)

Once upon a time there was no peer review in science. Instead, the editor made his own comments and edits, and then published it or not. This system was fast. You only had to know one person, the editor. Send him a mail (a letter, not email!) with your submission, and then wait for the reply. This is in fact how most of scientific history worked, and the great discoveries were published in this manner. Later in the 1960s or so, peer review won in for various reasons. Now instead of the editor making his own decisions, he has to send out the submission to some other academics for review, and then wait for their recommendations. As these other academics are almost always unpaid, this process can take a while: usually months, sometimes years. Peer review is marketed as a means of quality control. Surely, it works for this purpose, But so does editorial review (editor making his own decisions). For malformed, gibberish papers, you don’t need 3 reviewers to spend 4 months to tell the editor the obvious.

OK, maybe the editor doesn’t know every subarea of his field, so he may need to defer to someone who does know the right subfield. The general approach here is to have subeditors. They could then make the decision. But they now instead get to pick the reviewers. Sometimes there is disagreement among the (sub)editors, and the editor-in-chief (the top dog) will decide. The editors generally know the reviewers they pick, so they have a reasonable guess at or know the opinions of these. Thus when they send the reviewers a controversial paper, they will also be able to say with high confidence what the reviewer’s opinion will be. Thus, the editor is effectively in charge of deciding the fate of controversial papers by proxy. It is a convenient but inefficient setup. If the authors get rejected and complain, the editor will simply say “It’s not my fault. The independent reviewers thought your paper was dog shit, so try somewhere else”. In reality, the editor may have chosen 3 people who dislike the theory advocated in the paper. It doesn’t have to be normal politics (left-right) related, it can be favorite theory of schizophrenia ‘politics’, i.e. schools of thought. So really, the editor still has the power but he can hide behind the reviewers which he conveniently selected.

The cost of all this is that scientific publishing now takes a lot longer than it used to take. In fact, it gets worse. Everybody wants to publish in the same ‘top’ journals. The top journals are not really publishing any better science insofar as objective quality metrics are concerned. However, they do get more attention, and this determines careers as attention results in citations. Economics is famous for its insane system where one can only get a good job by publishing in one of the few ‘good’ economics journals. There are also some journals that publish science from all areas and get a lot of attention. These are the tabloids, but scientists love them, because they give you a lot of attention, and thus citations. These are Nature and Science. Due to the fact that everybody wants to be published in these journals, and these journals want to keep their reputation as ‘high quality’ hard to get into, they receive 1000s of submissions a year, and they reject 95% of them or more. Then, as scientists still want to get published in the more ‘prestigious’ (meaning popular) outlets, they try the second highest one they can think of. That one will have a rejection rate a bit lower than the first one, but still high, say 90%. If they get rejected again, they send it to the third most popular journal, and so on. Eventually, the paper will get published. Essentially any scientific paper can get published somewhere if you just keep trying. It’s a matter of stamina for doing dull paperwork (journals have different formatting, length, figure etc. requirements that you have to comply with). This is rational for scientists who want to optimize their careers, but collectively suboptimal for science as everything takes a lot longer, isn’t higher quality, and there’s a massive amount of time wasted formatting papers, and reviewing the same paper multiple times. It wastes extraordinary amounts of time chasing the most popular outlets instead of getting the work published immediately. The solution to this self-made, institutional problem is to publish papers twice. Once without review, and once after you jump thru some hoops somewhere. The first publication we these preprints (they are not printed yet). (Preprints are also made to circumvent Big Publisher’s copyright control system of science as they are open access.) Now, we know that scientists don’t really believe peer review works because they cite preprints all the time as if they were the real deal. After all, if scientists had to say they wouldn’t cite work that hadn’t been approved by a committee peer-reviewed, they would be admitting that they are unable to ‘peer’ review the work themselves. So instead we live in the double publication world. Often you can find papers in economics that have been living their lives as preprints for years, even a decade before a formal publication was achieved i.e., someone bothered to try enough journals, or met an editor at a cocktail party who was willing to stack the reviewers favorably. Sometimes they just live on forever as perpetual preprints. This stuff is all very irrational and we really need some adults to man up and fix things!

Phew. Rant over! Seems insane? Is that stuff about peer review being a recent thing really true? Yes. For instance, this 2014 piece in Scientific American tells us about the history of pre-publication peer review:

Peer review was introduced to scholarly publication in 1731 by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, which published a collection of peer-reviewed medical articles. Despite this early start, in many scientific journal publications the editors had the only say on whether an article will be published or not until after World War II. “Science and The Journal of the American Medical Association did not use outside reviewers until after 1940, “(Spier, 2002). The Lancet did not implement peer-review until 1976 (Benos et al., 2006). After the war and into the fifties and sixties, the specialization of articles increased and so did the competition for journal space. Technological advances (photocopying!) made it easier to distribute extra copies of articles to reviewers. Today, peer review is the “golden standard” in evaluation of everything from scholarly publication to grants to tenure decision (in the post I will focus on scholarly publication). It has been “elevated to a ‘principle’ — a unifying principle for a remarkably fragmented field” (Biagioli, 2002).

Those interested in details can read e.g. A Century of Science Publishing: A Collection of Essays (2001), which has a chapter covering the history.

The above might seem bad enough, but it gets worse. What if the scientists who were assigned reviewing duty didn’t really do this based on the merits alone, but used a strong prior based on social status of the author? I mean, we would call this status bias. From a Bayesian perspective it’s the same as having a strong initial belief that works by famous scientists is good. I mean, if the guy is good enough for a Nobel Prize, who I am to question his math even if it looks wonky? There’s a new study making the rounds looking into this question. Brian Nosek is promoting it on Twitter. He is himself a famous scientist (he’s behind the Open Science Foundation):

He has a personal anecdote about this too from back when he wasn’t famous:

The paper is this one. Fittingly, it’s not peer-reviewed so it’s probably pseudoscience a preprint:

- Huber, J., Inoua, S., Kerschbamer, R., König-Kersting, C., Palan, S., & Smith, V. L. (2022). Nobel and novice: Author prominence affects peer review. Rudolf and König-Kersting, Christian and Palan, Stefan and Smith, Vernon L., Nobel and novice: Author prominence affects peer review (August 16, 2022).

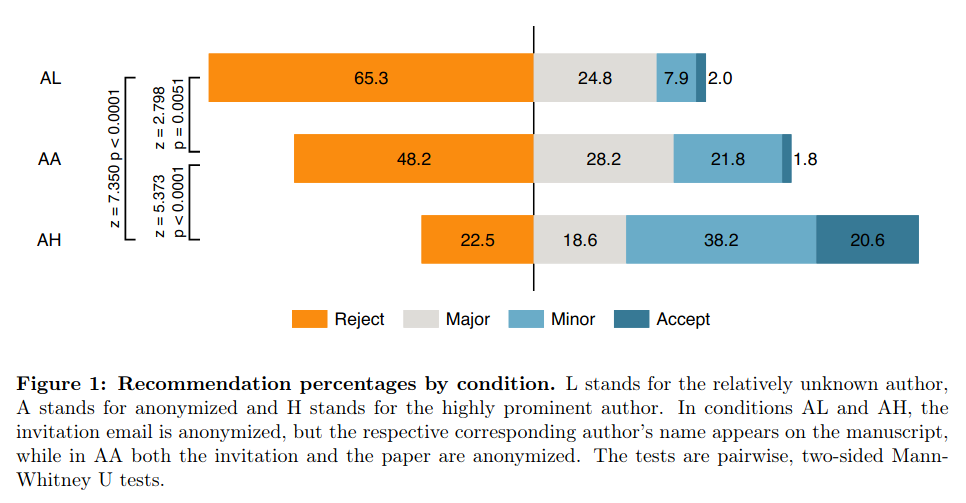

Peer-review is a well-established cornerstone of the scientific process, yet it is not immune to status bias. Merton identified the problem as one in which prominent researchers get disproportionately great credit for their contribution while relatively unknown researchers get disproportionately little credit (Merton, 1968). We measure the extent of this effect in the peer-review process through a pre-registered field experiment. We invite more than 3,300 researchers to review a paper jointly written by a prominent author – a Nobel laureate – and by a relatively unknown author – an early-career research associate -, varying whether reviewers see the prominent author’s name, an anonymized version of the paper, or the less well-known author’s name. We find strong evidence for the status bias: while only 23 percent recommend “reject” when the prominent researcher is the only author shown, 48 percent do so when the paper is anonymized, and 65 percent do so when the little-known author is the only author shown. Our findings complement and extend earlier results on double-anonymized vs. single-anonymized review (Peters and Ceci, 1982; Blank, 1991; Cox et al., 1993; Okike et al., 2016; Tomkins et al., 2017; Card and Della Vigna, 2020) and strongly suggest that double-anonymization is a minimum requirement for an unbiased review process.

The methods are straight forward. They collected a list of potential reviewers from recent papers. Then they write an invitation email to review it. The email a given person received was randomly varied, so it’s a randomized controlled trial. There were two authors of the paper they had people review, and they varied whether they were mentioned or not. One was a famous Nobel Prize winner, and the other some African guy. Vernon L. Smith and Sabiou Inoua. Never heard of them but perhaps you have. They had them write a joint paper (that isn’t public so the reviewers couldn’t find it), so there is a real paper involved. They looked at two outcomes. First, whether academics agreed to review the paper or not based on only reading the abstract and seeing or not seeing the author names. Second, how they evaluated the paper for those that agreed to review it. The first concerns whether people even want to spend time doing this work for free. The second what their opinion of the paper is, or at least, whether they want to publish it. Note that one might want to publish papers for reasons unrelated to quality, such as to increase the prestige of a journal. If tomorrow some Nobel Prize winner submitted a paper to OpenPsych or Mankind Quarterly, it would surely be good PR if it was published.

As they sent it out to 3300 academics for evaluation, the sample size is quite good and they don’t need wonky statistics because of the simple research design. They varied the email in two ways. Since there’s two authors, one can show or hide each of their names. So one can look at the effect of including a famous person or not, and the effect of including a nobody or not. They find that including a nobody or keeping them anonymous doesn’t do much. It was slightly better to hide them but not beyond what one would expect by chance alone (p > .05). In contrast, including a famous person increased the review acceptance rate by about 8%points, which is an increase of about 30% (31% to 39%). So the results are not dramatic but notable. Since a lot of people still agreed to review, it’s not clear this would affect the ultimate outcome of a submitted paper much.

Secondly, among those who reviewed the paper (about 35% of those invited), one can look at the ratings recommend they gave the editor regarding the paper, shown in the figure. There’s a massive difference. For the extreme outcomes: accept immediately was increased about 10x (2.0 to 20.6%), and reject immediately was decreased by about 3x (65.3 to 22.5%). But one cannot say from these recommendations whether reviewers were being affected by social status or whether they were being strategic (‘would be good to publish this paper in this journal that I review for’). To get around this, the authors also looked at paper quality ratings:

The quality ratings show the same thing. Markedly higher ratings for the paper based when it was written by a famous scientist vs. not. Also, revealing the name of a nobody results in worse reviews. This is curious. There’s several ways one can think about this. First, maybe the scientists are really Machiavellian and lie about the quality ratings too in order to promote a paper by famous person, or suppress a study by a nobody. I don’t see much reason to think this. Most reviewers have no ties to the journal they were reviewing for as such, so why go through with the lying? No gains for them. Second, scientists don’t pay much attention, they only skim the papers they review. Because of this they employ a strong prior based on the authors and only slightly modify this based on the actual paper contents. That’s pretty much the anti-thesis of meritocracy in science as it’s a straight violation of Merton’s universalism norm: “scientific validity is independent of the sociopolitical status/personal attributes of its participants.”. Still, we cannot say that it is strictly irrational. The reviewers are academics who worked for free to evaluate some paper. They had a quick look, and it seemed OK/bad. But they didn’t look too carefully, so they used the authors’ reputations as cue as well. Nothing irrational about this strategy. It’s lazy, sure, but academics get a lot of invitations to review, so if you want to accept a lot of them you need to work smart. Authors have an incentive to review a lot of papers because this itself gives you some prestige as you can call yourself a review for journal X, and maybe later join their editorial board.

So, clearly, reviewer blinding is good for the nobodies right? Well:

In case that working paper versions of a manuscript have been published prior to journal submission, these results suggest that less prominent authors might profit from anonymizing their manuscripts by giving them a new title and rewriting the abstract (so that the papers are more difficult to find on the web) and submitting them to journals with double- anonymized review. This conclusion is, however, premature. In the Supplementary Information, we show that those reviewers that accept the invitation to review the paper despite being informed that the corresponding author is the less prominent researcher (in condition LL) are milder in their judgements than reviewers that respond to the anonymized invitation. This self-selection effect benefits the less prominent author and (partly) counteracts the negative component of the status bias of the less prominent author’s manuscript being evaluated less favorably. Although the net effect still points in the direction of less prominent authors benefiting from fully anonymized review, the difference to single-anonymized review is no longer statistically significant for the less prominent author (while the reversed difference for the prominent author remains highly significant).

So people who chose to review papers by nobodies are more lenient. These may be do-gooders who want to help an up-and-coming guy, or maybe wokes who are trying to White Knight an African guy in this case. Still, it works out to be a net benefit in the sense that it forces evaluation based on the merits, and removes the positive effect of a famous author, even if the self-selection removes the negative effect of being a nobody.

Can we trust these findings? I said these results were new, and new results are dubious. Well, these ones in particular are new, but the general results are not. Here’s two other studies. One from 2006:

- Ross, J. S., Gross, C. P., Desai, M. M., Hong, Y., Grant, A. O., Daniels, S. R., … & Krumholz, H. M. (2006). Effect of blinded peer review on abstract acceptance. Jama, 295(14), 1675-1680.

Context Peer review should evaluate the merit and quality of abstracts but may be biased by geographic location or institutional prestige. The effectiveness of blinded peer review at reducing bias is unknown.

Objective To evaluate the effect of blinded review on the association between abstract characteristics and likelihood of abstract acceptance at a national research meeting.

Design and Setting All abstracts submitted to the American Heart Association’s annual Scientific Sessions research meeting from 2000-2004. Abstract review included the author’s name and institution (open review) from 2000-2001, and this information was concealed (blinded review) from 2002-2004. Abstracts were categorized by country, primary language, institution prestige, author sex, and government and industry status.

Main Outcome Measure Likelihood of abstract acceptance during open and blinded review, by abstract characteristics.

Results The mean number of abstracts submitted each year for evaluation was 13 455 and 28.5% were accepted. During open review, 40.8% of US and 22.6% of non-US abstracts were accepted (relative risk [RR], 1.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.75-1.88), whereas during blinded review, 33.4% of US and 23.7% of non-US abstracts were accepted (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.37-1.45; P<.001 for comparison between peer review periods). Among non-US abstracts, during open review, 31.1% from English- speaking countries and 20.9% from non−English-speaking countries were accepted (RR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.39-1.59), whereas during blinded review, 28.8% and 22.8% of abstracts were accepted, respectively (RR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.19-1.34; P<.001). Among abstracts from US academic institutions, during open review, 51.3% from highly prestigious and 32.6% from nonprestigious institutions were accepted (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.48-1.67), whereas during blinded review, 38.8% and 29.0% of abstracts were accepted, respectively (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.26-1.41; P<.001).

Conclusions This study provides evidence of bias in the open review of abstracts, favoring authors from the United States, English-speaking countries outside the United States, and prestigious academic institutions. Moreover, blinded review at least partially reduced reviewer bias.

And another from 2017:

- Tomkins, A., Zhang, M., & Heavlin, W. D. (2017). Reviewer bias in single-versus double-blind peer review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(48), 12708-12713.

Peer review may be “single-blind,” in which reviewers are aware of the names and affiliations of paper authors, or “double-blind,” in which this information is hidden. Noting that computer science research often appears first or exclusively in peer-reviewed conferences rather than journals, we study these two reviewing models in the context of the 10th Association for Computing Machinery International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, a highly selective venue (15.6% acceptance rate) in which expert committee members review full-length submissions for acceptance. We present a controlled experiment in which four committee members review each paper. Two of these four reviewers are drawn from a pool of committee members with access to author information; the other two are drawn from a disjoint pool without such access. This information asymmetry persists through the process of bidding for papers, reviewing papers, and entering scores. Reviewers in the single-blind condition typically bid for 22% fewer papers and preferentially bid for papers from top universities and companies. Once papers are allocated to reviewers, single-blind reviewers are significantly more likely than their double-blind counterparts to recommend for acceptance papers from famous authors, top universities, and top companies. The estimated odds multipliers are tangible, at 1.63, 1.58, and 2.10, respectively.

Their results are different but about the same effect of preferring authors that are from well reputed countries, institutions, and speak the right language well (English). I think there’s a bunch of these studies already, all with clear results and large samples, so there’s not much reason to doubt the findings.

These kinds of results naturally lead some to call for the literal abolition of this kind of peer review:

- Heesen, R., & Bright, L. K. (2020). Is peer review a good idea?. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science.

Prepublication peer review should be abolished. We consider the effects that such a change will have on the social structure of science, paying particular attention to the changed incentive structure and the likely effects on the behaviour of individual scientists. We evaluate these changes from the perspective of epistemic consequentialism. We find that where the effects of abolishing prepublication peer review can be evaluated with a reasonable level of confidence based on presently available evidence, they are either positive or neutral. We conclude that on present evidence abolishing peer review weakly dominates the status quo.

One could attempt to change the existing journals back to editorial review (faster but probably same amount of bias), or one could implement editor blinding. As changing institutions is very difficult, I am pessimistic about these efforts. Probably the best bet would be to make new journals that avoid these kinds of biases and slowness problems. One such is the Seeds of Science:

Scientific ideas, especially the truly innovative ones, are like seeds – they need fertile ground and tender care in order to grow to their true potential.

Seeds of Science (ISSN: 2768-1254) is a journal and community dedicated to nurturing promising ideas (“seeds of science”) and helping them blossom into scientific innovation. We have one primary criterion: does your article contain novel ideas with the potential to advance science? Peer review is conducted through voting and commenting by our diverse network of reviewers, or “gardeners” as we call them (free to join, more information available here). Visit the about page or read The Seeds of Science Manifesto to learn more about our mission and philosophy.

SoS has some success, but I think the right way would be to team up with some famous scientists at good institutions that dislike the current system and have them agree to spearhead the new one by publishing there themselves a lot, thus granting them prestige by association. That’s how the various other new journals that revolves around open access came to prominence. These are multi-journals like PLOSone and MDPI. These journals are usually for-profit, so they are expensive. Artificially so because they can make more money that way. There’s a variety of less known journals that do this much cheaper, because of course publishing a scientific journal does not really cost 3000 USD, but rather 50 or so. Since these newer alternatives are mostly run by nobodies, they don’t get much attention. Our own journal OpenPsych is an example of this, except it’s entirely for free (I funded it). It does have pre-publication peer review, but it’s open/transparent so one can see what’s going on.

From a personal perspective, I find these kinds of findings unsurprising. I am not merely a nobody, I’m infamous, mainly due to the long-term (6+ years) efforts of the deranged stalker Oliver D. Smith and the RationalWiki (RatWiki). In the good old days of 12 February 2016, Oliver started his harassment campaign by impersonating some guy called Ben Steigmans. This was actually in revenge for me banning him from a forum. Oliver loves to join random peoples forums, then act poorly, get banned, and then go on multi-year stalking campaigns against them. Be that as it may. Anyone who is a productive, public dissident can be expected to get harassed by either the state itself or its willing helpers like Oliver/RatWiki, Paypal, Amazon, banks, and so on. That’s just the price of being a dissident, now as in history, so I don’t want to complain too much about it as I chose this path willingly.

Suppose you acquire a RatWiki or some other notorious reputation by other stalkers or attack journalists (e.g. The Tainted Sources of ‘The Bell Curve’), then peer review is even worse for you. First, you have to go through the editor. The editor himself will see that you are infamous and may be inclined to reject your paper entirely on whatever or no grounds. If you make it past this initial screening, the editor might still dislike your paper, so he will give you some hostile reviewers, who in 3-6 months time will reject your paper based on seemingly scientific sounding reasons that just happen to correlate perfectly with their political ideology. “Science has spoken” he will say if you try any appeals. So you eventually will have to publish in a less popular journal, or self-publish it (on your blog, say). Then comes the second part of the attack. The critics will now say: “Look, this work wasn’t peer reviewed/wasn’t properly peer reviewed/was published in a low quality journal, so it sucks and we should dismiss it.”. What a beautiful system! Still, dissident papers do make it through peer review from time to time. This can be due to sheer luck. Maybe the editor was fair, and he selected some ‘random’ reviewers (i.e., the first people who replied to his invitation to review), and these just happened to be favorable to the paper. Or maybe the editor was secretly a dissident too, or pro-diversity of opinion, so he made sure to pick some favorable reviewers. Naturally, editors don’t go around advertising this, as they would get attacked and fired themselves. As such, publishing in academic journals as a dissident involves getting to know a lot of editors (and subeditors), and figuring out who is secretly also a dissident and who will once in a while allow for a dissident paper in the journal they run. They can’t do this too often as their role would get questioned. In fact, sometimes even after a single dissident paper, editors can get bullied or fired. One editor who published a paper in defense of colonialism received death threats and capitulated:

This Viewpoint essay has been withdrawn at the request of the academic journal editor, and in agreement with the author of the essay. Following a number of complaints, Taylor & Francis conducted a thorough investigation into the peer review process on this article. Whilst this clearly demonstrated the essay had undergone double-blind peer review, in line with the journal’s editorial policy, the journal editor has subsequently received serious and credible threats of personal violence. These threats are linked to the publication of this essay. As the publisher, we must take this seriously. Taylor & Francis has a strong and supportive duty of care to all our academic editorial teams, and this is why we are withdrawing this essay.

The solution to editorial bias seems to be that we need more blinding. To prevent the editor from being biased, he has to be blind to the authors too. So that is what a triple blind system would look like. In this system, authors submit something into a website. The website then removes all the names, emails and so on, and sends the abstract to the editor for evaluation. He can then ship it further to a subeditor, or send out review invitations, who will be equally blind to the authors. (This is somewhat an illusion as people can often guess the author’s identities.) I am not sure I know any journal that uses this feature. There are woke people who advocate for triple blinding because they want to remove the biases in favor of the aforementioned groups, who are mostly old European men. That’s fair. Of course, they may not realize that their own efforts will also help dissidents that they hate. Would they still be willing to advocate for this if they realized that? Maybe! Kathryn Paige Harden has previously noted how open science efforts — open data and open code — helps dissidents do science too, and that this is a problem:

Maybe the reformers can come up with a method for removing the bias in peer review against non-Europeans and low prestige institutions while still keeping the bias against dissidents. I mean, it seems easy enough, they should just set some explicit quotas or grant extra points in the peer review evaluations based on the authors’ characteristics. 1 points for being a woman. 2 points for being nonbinary, 1 point for homosexuality, ½ for having divorced parents, 3 for being African and so on. Basically ask authors to take the intersectionality score survey and report their score. This approach would be the same as used in university admissions (300+ SAT points for being African), recruitment in the public sector and so on, so it wouldn’t surprise me at all if woke science also adopted this.