Adrian Wooldridge is currently popular with his book The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World (2021). I read the book a while ago, but forgot to do a full book review. Inspired by recent events, I was brought back to this book and thought I would write up a review based on my notes.

The book is about how great meritocracy is. It goes over all sorts of historical examples where meritocracy wasn’t yet implemented, and various civil servant positions were just used to enrich the holders. The book describes itself thus:

Meritocracy: the idea that people should be advanced according to their talents rather than their birth. While this initially seemed like a novel concept, by the end of the twentieth century it had become the world’s ruling ideology. How did this happen, and why is meritocracy now under attack from both right and left?

In The Aristocracy of Talent, esteemed journalist and historian Adrian Wooldridge traces the history of meritocracy forged by the politicians and officials who introduced the revolutionary principle of open competition, the psychologists who devised methods for measuring natural mental abilities, and the educationalists who built ladders of educational opportunity. He looks outside western cultures and shows what transformative effects it has had everywhere it has been adopted, especially once women were brought into the meritocratic system.

Wooldridge also shows how meritocracy has now become corrupted and argues that the recent stalling of social mobility is the result of failure to complete the meritocratic revolution. Rather than abandoning meritocracy, he says, we should call for its renewal.

Table of contents:

- Introduction: A Revolutionary Idea

- PART ONE Priority, Degree and Place

-

1 Homo hierarchicus

-

2 Family Power

-

3 Nepotism, Patronage, Venality

- PART TWO Meritocracy before Modernity

-

4 Plato and the Philosopher Kings

-

5 China and the Examination State

-

6 The Chosen People

-

7 The Golden Ladder

- PART THREE The Rise of the Meritocracy

-

8 Europe and the Career Open to Talent

-

9 Britain and the Intellectual Aristocracy

-

10 The United States and the Republic of Merit

- PART FOUR The March of the Meritocrats

-

11 The Measurement of Merit

-

12 The Meritocratic Revolution

-

13 Girly Swots

- PART FIVE The Crisis of the Meritocracy

-

14 Against Meritocracy: The Revolt on the Left

-

15 The Corruption of the Meritocracy

-

16 Against Meritocracy: The Revolt on the Right

-

17 Asia Rediscovers Meritocracy

- Conclusion: Renewing Meritocracy

As usual, I will be quoting from the book in blocks to give full context (no misrepresentation), and provide my own comments.

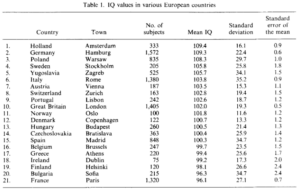

Bill Clinton’s belief that there is a tight connection between earning and learning is proving truer by the day. In the United States, for example, a young college graduate earns 63 per cent more than a young high-school graduate if both work full time – and college graduates are much more likely to have full-time jobs.10 This college premium is twice what it was in 1980 and is continuing to grow. Raw intelligence is one of the best predictors of success in life. Peter Saunders, a social-mobility researcher, estimates that performance in an IQ test at the age of ten predicts a child’s social class three times better than their parents’ social class does.11 A study of a cohort of British children born in 1970 found that those in the top quartile of IQ scores at the age of ten were much more likely to reach elite social positions (28 per cent) than those in the bottom quartile (5.3 per cent).12

This is the same changing-distributions fallacy I wrote about before, but is that the best name we can find for this? The reason the college premium is larger is not that intelligence is now more important, but that the mean intelligence levels of these two categories has changed over time due to more people entering college. This is a fake finding.

The meritocratic idea transformed Western society from the inside out. It changed the tenor of the elite by reforming the way that society allocates the top jobs and the nature of education by emphasizing the importance of raw intellectual ability. It did all this by redefining the elemental force that determines social structure. ‘When there is no more hereditary wealth, privilege class, or prerogatives of birth …’ Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, in one of the earliest attempts to understand what was going on, ‘it becomes clear that the chief source of disparity between the fortunes of men lies in the mind.’31

Well, if Greg Clark is right — and he probably is — then meritocracy was always there. Sure, there used to be less of it, but it was always possible for better minds to rise to the top, and lesser minds could find themselves suddenly poor. There’s a lot of stories of aristocrats who had lost their fortune and lands, and commoners who found themselves in high positions. There wasn’t really any hard-break with prior times without meritocracy to the present with it. It’s an illusion. Aristocrats were always smart, and since they bred mainly among themselves, they tended to stay smart too.

Dynasty ensured that the relationship between social position and personal ability was, at best, arbitrary. Anybody who thinks that abilities are primarily determined by nurture rather than nature should spend a little time studying the history of Europe’s royal dynasties. If you happened to have an able ruler, then all well and good, but ability and lineage seldom went hand in hand, and even extreme lack of ability was no barrier to succession. Being the oldest (preferably) male heir was all that mattered. Royal dynasties increasingly loaded the dice against themselves when it came to ability by restricting their choice of mates to fellow members of royal dynasties: by Queen Victoria’s reign, the kings of most European countries were all related to each other.Walter Bagehot argued that ‘a royal family will generally have less ability than other families’ (and even speculated that in 1802 every hereditary monarch in Europe was insane).25 There were certainly extreme examples of mental weakness in royal lines. Henry VI of England was mentally incapacitated. George III suffered prolonged bouts of insanity. The Habsburgs were so prone to inbreeding that people joked that they married their cousins and slept with their siblings. The Emperor Charles V had such an extreme case of ‘Habsburg jaw’ that the upper and lower parts of his mouth didn’t mesh (a carriage accident also robbed him of his front teeth). He was always intellectually limited – ‘not very interesting’, in the words of David Hume – but deteriorated badly in old age and spent his days taking clocks apart and having his servants make them tick in unison.26 Philip II’s eldest son and heir, Prince Carlos, suffered from delusions and dementia, a condition that was not helped by attempts to cure him by forcing him to share his bed with a mummified saint.27 Charles II of Spain was a mass of genetic problems: his head was too big for his body and his tongue was too big for his mouth, so that he had difficulty speaking and constantly drooled; his first wife complained that he suffered from premature ejaculation and his second wife that he was impotent; on top of all that, he suffered from convulsions.28 Other leading Habsburgs had evocative names such as Juana the Mad and Twat-Face (Fotzenpoidl).

Wrong-headed. By only marrying among themselves, they could keep regression towards the mean at bay. If they had indiscriminately married commoners, their genotypic intelligence would have quickly declined. It is also true that hereditary mental illness was not uncommon, especially in the later times of Habsburgs. Denmark had a king with schizophrenia as well. The optimal approach is to marry mostly among themselves, and then add-in a particularly good commoner once in a while (after they have earned some title), while discarding the incompetent fellow aristocrats. This is roughly what happened. The need for various strategic alliances of course also had a role, and sometimes an unfortunate one. To pick the Danish example, while the king was insane, a German gifted commoner Johann Struensee managed to infiltrate the kingdom, using his role as the court doctor. He then paired up with the queen for an affair, while the king was running around doing schizo things (drinking and whoring). While in power, Struensee implemented a number of enlightenment-style reforms such as reduced censorship of the media. He didn’t last long, and got beheaded only 2 years later. However, he did manage to have a daughter with the queen (herself from England, married for diplomatic reasons). This daughter was then part of the royal family on her own right despite having no genetic connection to Denmark via the king. Despite this she married into other aristocrats. You can watch the movie A Royal Affair for the details.

The Song emperors (960–1279) established many of the features of the system that survived until the twentieth century. They focused the examinations more exclusively on the intellectual merits of the candidates rather than on their moral character, believing that the possession of intellectual merit was in itself evidence of moral worth, a position later echoed by Macaulay. They established three levels of examination that operated on a three-year cycle. The examination system was briefly challenged by a few interruptions – the arrival of the Yuan dynasty from Mongolia in 1280 and various revolts by disgruntled aristocrats – but the Yuan dynasty reintroduced elements of the system in 1313 and the subsequent Ming and Qing dynasties preserved and improved it.

He doesn’t mention it, but there’s a bunch of research to back that up. Of course, we know that intelligence is negatively related to criminal behavior, whether this is measured by self-report or by the court records. In terms of psychology, there’s even correlations between intelligence and moral reasoning, though this line of research has regrettably fallen out of fashion. One can find old studies like the one by Campagna, A. F., & Harter, S. (1975):

A total of 44 mental age- and IQ-matched 10-13 yr old normal and sociopathic boys were administered L. Kohlberg’s moral development interview and the WISC. Results reveal that level of moral reasoning was higher for normal than for sociopathic Ss at both mental age levels. Within each group, high-mental-age Ss tended to have higher moral judgment scores than low-mental-age Ss, suggesting the presence of a general cognitive factor underlying moral development. The poorer performance of the sociopathic Ss was interpreted as supporting the formulation that sociopathy is related to an arrest in moral development. Discussion focuses on the relative lack of opportunities for role-taking and identification in the families of sociopathic children.

Here’s another two old studies: Speicher, B. (1994), Simon & Ward 1973.

The tough question for people is that if moral development and reasoning capacity varies with intelligence, and we generally consider this ability to be important for moral status, does that mean that high intelligence defendants should be punished harder, as their moral failing will in general have been stronger to commit such actions? If moral ability is thus correlated with intelligence, does that say anything about human worth? How is it that human worth magically stays the same for everybody when no one acts that way? This guy bites the bullet.

Speaking of equality, he quotes John Adams (2nd US president):

Adams also provided one of the clearest explanations of the distinction between substantive and formal equality that lies at the heart of the meritocratic creed:That all men are born to equal rights is true. Every being has a right to his own, as clear, as moral, as sacred, as any other being has. This is as indubitable as a moral government in the universe. But to teach that all men are born with equal powers and faculties, to equal influence in society, to equal property and advantages, through life, is as gross a fraud, as glaring an imposition on the credulity of the people, as ever was practiced by monks, by Druids, by Brahmins, by priests of the immortal Lama, or by the self-styled philosophers of the French Revolution.30Yet Adams was given to agonizing. In a letter to Benjamin Rush in 1809 he explained that hereditary aristocrats might be bulwarks against political vice:I believe there is as much in the breed of men as there is in that of horses. I know you will upon reading this cry out: ‘Oh, the Aristocrat! The advocate for hereditary nobility! For monarchy! and every political evil!’ But it is no such thing. I am no advocate of any of these things. As long as sense and virtue remain in a nation in sufficient quantities to enable them [sic] to choose their legislatures and magistrates, elective governments are the best in the world. But when nonsense and vice get the ascendancy, command the majority, and possess the whole power of a nation, the history of mankind shows that sense and virtue have been compelled to unite with nonsense and vice in establishing hereditary powers as the only security for life, property, and the miserable liberty that remains.31

In fact, most of the greats of old wrote things like that. Maybe he has some statues one can pull down somewhere.

These bold attempts to reinterpret merit as inborn intelligence and to measure innate intelligence with IQ tests encountered fierce opposition. For the arguments were not only breathtakingly bold, they also had revolutionary practical implications for everything from education to the military. Pedagogical conservatives fought intelligence tests on the grounds that they weren’t as good at spotting academic merit as traditional examinations. Pedagogical radicals argued that the new breed of psychologists underestimated the power of education to develop ability and unleash talent. All sorts of people objected to the hubris of the testing movement. ‘One does not allow the first person who comes along on the pretext that he is a psychologist, to decide in a few minutes whether one is or is not an acceptable sample of humanity,’ Albert Challand, a French psychologist, said, ‘and to settle definitively the possibilities that one might have for success in one’s career.’1Walter Lippmann, the doyen of American columnists, mounted a formidable attack on the new science in a series of articles in the New Republic in 1922 that foreshadowed almost all the later criticisms of IQ testing. The concept of intelligence is frustratingly vague, he argued; IQ tests are shoddy measuring sticks; there is no evidence they measure a fixed trait; and ‘intelligence’, whatever that might be, is only loosely correlated with success in life. He warned that ‘if intelligence testing ever really caught on, the people in charge of it would occupy a position of power which no intellectual had held since the collapse of theocracy’.2 ‘I hate the impudence of a claim that in fifty minutes you can judge and classify a human being’s predestined fitness in life,’ he wrote in a later article in the Century Magazine, echoing Challand. ‘I hate the pretentiousness of that claim. I hate the abuse of scientific method which it involves. I hate the sense of superiority which it imposes.’3

Walter Lippmann sounds more and more cringe every time I read anything he has written. All emotion and no science. I don’t know why everybody keeps quoting him after 100 years. How did some journalist get this kind of status? I can’t think of anything he said that was important and correct. I hope our future descendants won’t be hearing about Angela Saini, Adam Rutherford, Malcolm Gladwell etc. in 100 years time.

IQ testing got its great practical breakthrough with America’s entry into the First World War in 1917. The army commissioned a group of psychologists, most notably Lewis Terman and Robert Yerkes, to classify more than 1.7 million soldiers; and the psychologists quickly devised two sorts of mass tests, alpha tests for people who were literate in English, and beta tests for those who were not. They were soon processing more than 10,000 examinees a day – an extraordinary achievement for a new and controversial technique. Unit commanders paid increasing attention to the results of the tests in deciding which soldiers to keep and which to try to pass on to other companies: some 7,700 recommendations for discharge and 28,000 for transfer were forwarded to army discharge boards on the basis of the tests.29 The tests might not be able to provide a direct measure of bravery or the power of command, Yerkes admitted, but then added, on the basis of no clear evidence, that these qualities ‘are far more likely to be found in men of superior intelligence’.30

Yerkes was of course correct. There’s a bunch of military data on outcomes of soldiers related to their intelligence. It’s universally positive for all types of performance. Here’s some results from Project A by way of Gottfredson 1997:

Odd though it was, Genetic Studies of Genius nevertheless had merits. It reinforced the idea that genius could be studied alongside other natural phenomena. It exploded popular stereotypes of gifted children that had their roots in the Romantic idea of mad geniuses. Far from being small and sickly, Terman discovered, they were taller and fitter than average; far from being scrofulous misfits, they were better adjusted than average. The Termites went on to have highly successful careers, earning higher salaries and better professional rewards than a control group.Terman’s fixation on ‘natural genius’ was driven in part by his autobiography – he was one of ten children, suffered from tuberculosis as a child, attended a one-room schoolhouse and spent his summers working on the farm – and in part by his enthusiasm for national efficiency, a fashionable idea when he was growing up. ‘Whether civilization moves on and up,’ he argued, ‘depends most on the advances made by creative thinkers and leaders in science, politics, art, morality, and religion. Moderate ability can follow or imitate, but genius must show the way.’48 Geniuses might not be the stunted freaks of popular lore, but if you put them in classes that failed to stretch their abilities they might well become misfits and rebels.

And Terman was right too. The last post on this blog was about our vindication of the smart fraction theory.

Until the 1960s, mental measurement found its most passionate supporters on the left and its most serious critics on the right. Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the founders of the American transcendentalist movement, advocated the creation of an ‘anthropometer’ that could gauge everybody’s innate merit. ‘I should like to see that appraisal applied to every man, and every man made acquainted with the true number and weight of every adult citizen, and that he then be placed where he belongs, with so much power confided to him as he could carry and use.’59 J. B. S. Haldane, a leading member of the British Communist Party and an editor of the party’s mouthpiece, The Daily Worker, dismissed ‘the curious dogma of the equality of man’.60 ‘We are not born equal, far from it. The best community is that which contains the fewest square pegs in round holes, bricklayers who might have been musicians, company directors who, by their own abilities, would never have risen above the rank of clerk.’61 Haldane believed that, if anything, supporters of grammar schools didn’t go far enough: ‘the most important experiment, to my mind, would be to start a school whose membership was confined to really intelligent children. Such children could easily reach the standards of the average university graduate at eighteen.’62In Russia, the early Bolsheviks were devotees not just of IQ testing but of craniometry. In 1923, as Lenin lay dying, Trotsky told the Party that ‘Lenin was a genius, a genius is born once a century, and the history of the world knows only two geniuses as leaders of the working class: Marx and Lenin’, and to prove the general point (soon dissociated from ‘the traitor Trotsky’), the Party invited a German neurologist, Oskar Vogt, to come to Moscow in 1925 to study their recently deceased leader’s brain to understand why he was so exceptional. Vogt dissected the brain into more than 30,000 pieces, analysed the pieces in all sorts of ways and, after months of deliberation, came to the conclusion that Lenin was indeed a ‘mental athlete’ (Assoziationsathlet). Vogt secured Stalin’s support to establish the V. I. Lenin Institute for Brain Research in a lavish mansion expropriated from an American businessman: the institute served as a research centre, studying the brains of Lenin and other leading revolutionaries, and housed a Pantheon of Brains, camprising a large collection of the brains of prominent Soviet intellectuals. It still exists but remains closed to foreign scholars.63By contrast, many conservatives regarded mental measurement as the devil’s work. Lord Percy of Newcastle, the Conservative president of the Board of Education under Stanley Baldwin and a younger son of the 7th Duke of Northumberland, the grandest grandee in northern England, felt that those psychologists who held that children inherited a fixed IQ had fallen ‘easy victims to the calvinistic nightmare of predestination’.64 T. S. Eliot argued that ‘an educational system which would automatically sort out everyone according to his native capacities’ would ‘disorganise society and debase education’.65 Edward Welbourne, the reactionary master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, dismissed IQ tests as ‘devices invented by Jews for the advancement of Jews’.66The best way to expose the foolishness of the Gould–Kamin school of thought is to set the IQ testers in their historical context: reconstruct the social structures and social attitudes of the first half of the twentieth century and it’s impossible not to be struck by the radicalism of the IQ testing movement. The champions of mental measurement were advocating nothing less than a reconstruction of the established social order and the replacement of a ruling class based on lineage and tradition with one based on ability and achievement. ‘Reactionaries’ have never come in such a revolutionary form.

It’s amazing to me how the historical communists made their beliefs work together. Modern communism is all about how all humans are really akshualy equal in everything that matters psychologically, and any deviation from this norm in social status is due to the devil capitalraciphobiaism. The old-school communists seem to have been much more interested in taking down the aristocracy and its hereditary wealth. They weren’t concerned that taking down the old elite would just produce a new hereditary elite.

The prejudice against ‘swots’ and ‘grinds’ became stronger in the 1920s thanks to the growing cult of the WASP. F. Scott Fitzgerald idealized Princeton as a place populated by willowy young men strolling from luncheon to tea without ever taking a detour to the library. Others were openly antisemitic in their vituperation against ‘greasy grinds’ who wasted their university years in study. In 1926, Yale produced a new admissions policy that was intended to put more emphasis on character. The student-run Yale Daily News praised the policy on the grounds that it would prevent the university from being overrun by ‘abnormal brain specimens’ but suggested that the admission tutors go further: candidates should be required to submit photographs of their fathers along with their applications.78

1920’s version of post physique. Based? But it didn’t last long.

This treatment of women depended on two articles of faith. The first was the doctrine of ‘separate spheres’, which held that men and women held sway in different areas of life, each of which had its own distinctive functions and regulations: women ruled in the ‘private sphere’, which was focused on home-making and child-rearing, while men ruled in the public sphere, which was devoted to competition and money-making. ‘Their vocation is to make life endurable,’ a Tory MP told the Commons. The two spheres complemented each other: the home was a necessary counterbalance to the capitalist world of self-seeking. One American advice manual, A Voice to the Married (1841), told wives in no uncertain terms that they had a duty to provide their husbands with a haven in a heartless world: ‘an Elysium to which he can flee and find rest from the sorry strife of a selfish world’.6 Without the ‘haven’, administered by what Coventry Patmore dubbed, in 1854, ‘the angel in the house’, the world would be too heartless to be endured, but without the heartless capitalist doing battle in the marketplace there would be no money to sustain civilization.

The second was the idea that women are the ‘weaker sex’, at once frailer and finer than men. This started with a simple physiological observation – that women are, on average, shorter and physically weaker than men – and then proceeded to construct a mighty skyscraper of prejudice on this foundation. Women are slaves to their body’s menstrual rhythms, which can render them moody and distracted. They are more intellectually and physically fragile than men – ‘Frailty, thy name is woman,’ as Shakespeare has it in Hamlet. On the other hand, they are closer to heavenly things – like a ‘milk-white lamb that bleats for man’s protection’, as Keats put it. Expose them to horrible sights and they will fall apart. Subject them to hard thinking and they will become deranged. Women are like beautiful flowers which make the world more splendid but wither and die in harsh conditions.

Surely hilarious and exaggerated, but in retrospect, we gotta wonder if not these people were unto something.

At the high point of Social Darwinism, in the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras, these two ideas were reinforced by a third, that women were lower down the evolutionary scale than men. Charles Darwin set the ball rolling in The Descent of Man (1871), arguing that, across the natural world, full-grown females are more backward than full-grown males. Gustave Le Bon, the author of The Psychology of Crowds (1895), ran with the ball: women ‘represent the most inferior forms of human evolution … they are closer to children and savages than to an adult, civilized man. They excel in fickleness, inconstancy, absence of thought and logic, and incapacity to reason.’ He dealt with the problem of female geniuses such as George Eliot with a chilling aside: ‘Without doubt there exist some distinguished women, very superior to the average man, but they are as exceptional as the birth of any monstrosity, as, for example, of a gorilla with two heads; consequently, we may neglect them entirely.’8

To prove his case, Le Bon went around measuring women’s heads, along with the heads of ‘savages’, ‘geniuses’, and so on, even inventing a portable cephalometer which he could whip out whenever the mood took him. The result was clear to him: women have smaller heads than men, mediocre men have smaller heads than talented men and ‘inferior races’ have smaller heads than ‘superior races’. He also employed (somewhat random) archaeological evidence to prove that these differences had become greater over time, as the differential pressure of evolution made men more ‘dominant’ and women more ‘passive’.

The OG craniometrician! Of course, these results are all correct insofar as head sizes are concerned, so someone should check this guy’s results and see if they fit with modern results. I’ve never heard of him in the endless debates about Morton’s skulls.

The earliest intellectual blow to Johnson’s vision of solving America’s oldest problem came with the so-called Coleman Report: a massive study of educational spending in 4,000 schools with nearly 600,000 students produced in 1966 by a sociologist, James Coleman. Coleman concluded, much to his own surprise as well as everyone else’s, that there was little difference between white-majority and black-majority schools when it came to physical plant, curricula or teacher characteristics. There were certainly big differences in performance – differences that continued to widen as children spent more time in school – but these differences could not be explained in terms of how much was spent on schools. The one school characteristic that did show a relationship to scores in achievement tests was the presence of affluent families.

The conclusion of the report was shocking to a country that believed that problems could be fixed by spending money on well-intentioned social reforms. You couldn’t solve the problem of minority poverty simply by improving the quality of the physical plant. You had to go deeper into the structure of society – perhaps challenging America’s wide inequalities of reward, as the left argued, or perhaps looking at problems of the black family structure, which had been shattered by slavery, as the right, and particularly a new school of former Democrats known as neoconservatives, argued. The report was so shocking that the Johnson administration considered not releasing it, and eventually did the next best thing, releasing it on the Friday of a fourth of July weekend.

The Coleman report famously led Arthur Jensen to write his 1969 masterpiece: How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?. It is eminently readable after half a century, and holds up well too. It turns out that in social science, when you don’t cheat with the statistics, or import politics, science does work. The Coleman report, too, replicates just fine. Schools are not particularly important causes of academic achievement, or much else.

Another solution to the problem of racial integration – bussing – was even more unpopular than affirmative action. The bitterest fight took place on the Democrats’ home turf of Boston. Judge W. Arthur Garrity, a graduate of Harvard Law School and close friend of the Kennedy clan, decided to mix two schools together – South Boston High, in the heart of Irish ‘Southie’, and Roxbury High, in the heart of the black ghetto. The result was a social explosion, pitting race against race and the working class against the mandarins. State troopers were mobilized. Parents punched each other. Whites fled the school system: soon there were just 400 pupils attending South Boston High – guarded by 500 police.61 Racial hostility was reinforced: one study of the long-term impact of bussing on racial attitudes concluded, coolly but devastatingly, that ‘the data suggest that, under the circumstances obtaining in these studies, integration heightens racial identity and consciousness, enhances ideologies that promote racial segregation, and reduces opportunities for actual contact between the races’.62 Class hostility was added to racial hostility: Judge Garrity lived in genteel Wellesley, where the children were unaffected, and Michael Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor who sent in the troops, lived in equally genteel Brookline. This was clearly a case of the ruling class imposing their elevated principles on everybody’s children but their own. Bussing caused mayhem but did nothing to improve educational results: in 1974, Roxbury High and South Boston High had been the two worst-performing schools in Boston; a decade later, they were even worse.

Nothing has been learned from this. In Denmark, we have been importing Muslims the last couple of decades, and now we too are the proud owners of an ethnic underclass with all the usual problems. The bright minds in the government have decided that what we need to fix this is to compel students to go to the same high schools! Very retro. I’m sure this will be a great success and will report back when the good news come in.

The marriage of money and merit is being driven by two of humanity’s most basic instincts: our tendency to marry people like ourselves (assortative mating) and our desire to do the best for our children. We may continue to read our children stories about Cinderella marrying a prince, but in the real world university graduates marry other university graduates and high-school dropouts marry other high-school dropouts. Throw young adults together in the hothouse atmosphere of residential universities and there is a reasonable chance that they will mate. And if by some chance they don’t, there are always elite dating sites that can make up for lost time: the League, a dating service for Ivy League students, is informally dubbed ‘Tinder for the elites’. (Facebook itself started life as a dating site that was restricted first to Harvard and then to the Ivy League.) The proportion of men with university degrees who married women with university degrees nearly doubled between 1960 and 2005, from 25 per cent to 48 per cent, and the change may well have accelerated since then, helped in part by dating apps, which makes it easier for potential partners to screen each other for education.10

…

Assortative mating acts as a mighty multiplier of inequality: two married lawyers are substantially richer than two married shelf-stackers. It also has a much bigger impact on the overall tenor of society than the existence of a handful of billionaires somewhere in the stratosphere. One academic study of the United States shows that in 1960 a couple of high-school graduates who married each other earned about 103 per cent of the average household income. In 2005, a similar couple earned about 83 per cent of the average. At the other end of the spectrum, a couple in which both partners had done post-graduate work earned about 176 per cent of the mean household income in 1960 but 219 per cent in 2005. If people married each other at random, the overall level of inequality would be much as it was in 1960.11

This is the same fallacy as before: changing-distributions of the degrees means that a constant rate of assortative mating on educability will result in different observed rates within and between these arbitrary categories. This claim has even been disproven using genetics, as polygenic scores for education don’t care about these divisions, and show no changes in assortative mating over time.

One step up from helicopter parenting is tiger parenting. Amy Chua, a Yale law professor, caused a stir in 2011 with her semi-autobiographical the Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Her argument, summed up in an article in the Wall Street Journal, went like this:

A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids … Well, I can tell them, because I’ve done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do: attend a sleepover; have a playdate; be in a school play; complain about not being in a school play; watch TV or play computer games; choose their own extracurricular activities; get any grade less than an A; not be the No. student in every subject except gym and drama; play any instrument other than the piano or violin; not play the piano or violin.16

Though Ms Chua’s book provoked a mixture of horror and anxiety among her fellow parents, all she was really doing was taking elite parenting to its logical extreme.

Sounds like a fun childhood!

The Iraq War and the financial crisis both fit into a larger pattern: of experts pronouncing confidently on things that intimately effect the lives of the masses (bloodily so, in the case of the Iraq War) and getting it completely wrong. A 2003 Home Office report concluded that net immigration from Central and Eastern Europe would be between 5,000 and 13,000 immigrants a year. This helped to tip the Blair government’s decision not to apply a brake to East European immigration. In 2013, the ONS estimated that the actual figure was about 50,000. By 2014, there were nearly 1.5 million workers from Central and Eastern Europe living in the UK.9

Weird how governments that ease immigration laws always seem make this kind of prediction error. Here’s another one, Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart–Celler Act):

When Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the bill’s supporters seemed sure of one thing—its effects on the country’s population would be minimal. “The bill will not flood our cities with immigrants. It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society,” Sen. Ted Kennedy stated succinctly. His brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, made the same prediction: “[The bill] would increase the amount of authorized immigration by only a fraction.”

And Denmark continues to follow the great ideas of America, Foreigner Law of 1983, Danish state minister (president equivalent):

“I know that many Danes are anxious that opening borders could lead to Denmark being literally flooded by, for example, half or a whole million people from outside. That would scare people, but it doesn’t work that way.”

Denmark will soon hit 1 million foreigners, about 70% are non-Westerns (i.e., from outside EU and Anglo-lands). Immigration accelerated immediately after the law was changed. And the best part is that the state minister was a conservative.

These problems are made even more infuriating by what often looks like self-dealing. This was at its most striking with the global financial crisis: bankers who preached the doctrine of capitalism red in tooth and claw during the boom years suddenly discovered the virtues of state intervention when they needed help. It was repeated with the Covid crisis, when buccaneering globalists such as Richard Branson discovered the virtues of state aid. You can also see it at work in the divisive issue of immigration. Though members of the cognitive elite like to see their pro-immigration beliefs as proof of their enlightenment (in a survey of British public opinion by Chatham House, 57 per cent of the elite thought immigration has been good for the country, compared with just 25 per cent of the general public), they also have material interests at stake. For them, immigration means cheap servants to raise their children (a necessity when two parents are both pursuing brilliant careers) and cheap service workers in bars and restaurants. For manual workers, it might well mean somebody who is willing to do their job for less money and no benefits. In the global cities where meritocrats congregate, service jobs are dominated by recent immigrants who are willing to put up with miserable wages, long hours and crowded living conditions.23

The only good thing about this is that at least the elites have to do bear most of the tax burden for their new guests.

Lee Kuan Yew vies with Thomas Jefferson for the title of the philosopher king of the meritocratic idea. Lee was a model scholarship winner: he got the best school certificate results in Singapore in 1940, when the country was a colony of Great Britain, won a scholarship to Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, and graduated with a double starred first in law. For Lee, intellectual ability was the most precious commodity in the world – and the idea that ‘all men are created equal and capable of equal contribution to the common good’ was the most dangerous illusion. It was only by harnessing the mental power of the vital few that a country, particularly a slither of a country like Singapore, could achieve national greatness. ‘I am sorry if I am constantly preoccupied with what the near-geniuses and the above average are going to do,’ he once said. ‘But I am convinced that it is they who ultimately decide the shape of things to come.’

Lee took his Galton-like faith in genius to its logical conclusion. In 1983, he sparked a ‘great marriage debate’ when he suggested that elite men should choose highly educated women as wives. (His own wife had been a classmate of his and had beaten him on a couple of papers, in English and economics.) He established a matchmaking agency, the Social Development Unit, to encourage graduates to meet, match and hopefully hatch, and introduced a Graduate Mothers Scheme to encourage highly educated women to produce three or four children. (All this effort was, in fact, wasted, given the pattern of ‘assortative mating’ that we noted earlier and the state’s dismal record in persuading people to have more children.) In 1994, he provoked a great democracy debate when he revived J. S. Mill’s idea of a variable franchise. Surely a middle-aged family man with a stake in the future should have more votes than a young wastrel who is simply bent on sowing his wild oats – or a retiree just focused on his own failing health? (Again, this effort was wasted, given that Singapore’s democracy is tightly controlled by the state.)

Smart fraction in Singapore too.

A good way to measure the virtue of meritocracy is to look at what happens if you remove it. New York’s City College had a well-deserved reputation as the ‘Harvard of the proletariat’, taking thousands of poor adolescents, many of them the offspring of immigrants, and turning them into doctors, lawyers, academics and, in the case of nine alumni, Nobel Prize winners. In the run-up to the Second World War, City students included a host of people who went on to shape America’s intellectual life, including Daniel Bell, Nathan Glazer, Sidney Hook, Irving Kristol and Irving Howe, who wrote a marvellous account of his City years in World of Our Fathers (1976). Then in 1970 the university introduced an open-access regime, admitting anyone who had graduated from the city’s high schools. The result was a simultaneous boom in student numbers and a collapse in academic standards. By 1978, two out of three students admitted to the college required remedial teaching in the three ‘R’s.10 Drop-out rates surged. Talented scholars left. Protests and occupations became commonplace. In 1994, a task force, led by Benno Schmidt, pronounced the college ‘moribund’ and ‘in a spiral of decline’. The college only began to recover after 1999, when it abandoned open admissions as a failed experiment.

Ah, yes, but we haven’t learned anything. Now SATs, GREs are being removed as entrance requirements, and elite prep schools opened to all with predictable results. It reminds me of the people who wanted to replicate the great Hungarian high schools (gymnasiums) that produced so many geniuses. Haven’t seen any geniuses come out of Hungary since they changed the demographics.

Paradoxically, treating people as moral equals also entails treating them as moral agents, who, by exercising their moral agency, can become socially unequal. Meritocracy is the ideal way of making sense of this paradox. By encouraging people to discover and develop their talents, it encourages them to discover and develop what makes them human. By rewarding people on the basis of those talents, it treats them with the respect they deserve, as self-governing individuals who are capable of dreaming their dreams and willing their fates while also enriching society as a whole. ‘The ethical justification for meritocracy is not that people should be rewarded for their genes and upbringing,’ says Peter Saunders, ‘it is that everyone benefits when the talented are induced to hone their abilities to what other people demand in the marketplace.’14 Few would dispute that the old world of patronage and connection debased everybody involved, not just by treating patrons as masters of the universe but also by treating job-seekers as interchangeable clients rather than as unique individuals with unique gifts. The new world envisaged by egalitarians and communitarians does much the same thing: by treating people as interchangeable atoms it turns institutions into omnipotent patrons that can dispense their rewards as they will.

The most obvious argument, but somehow the likes of Paige-Harden can write an entire book dealing with genetics and success and not discuss the basic efficiency argument.

Finally, no book on meritocracy is complete without whining about The Bell Curve. The best way to do this is to not actually read The Bell Curve, and then argue against strawmen. There’s several examples in this book’s conclusion. It’s weird from an objective perspective because TBC is also a pro-meritocracy book which relied on mainstream scientific evidence at the time of writing. But despite its merits, it must always be attacked because it was a bit too honest about race differences.

In 1994, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray published a highly controversial book called The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life.25 The book did a disservice to the meritocratic idea in all sorts of ways, but two stand out: it argued that a truly meritocratic society would inevitably calcify into a caste society and it posited that the average IQ of black people is about ten to fifteen points lower than the average IQ of white people (which is in turn lower than the average IQ of Asian people). Both these arguments misrepresent the psychometric science upon which the book is supposedly founded.

Here’s TBC itself:

Unchecked, these trends will lead the U.S. toward something resembling a caste society, with the underclass mired ever more firmly at the bottom and the cognitive elite ever more firmly anchored at the top, restructuring the rules of society so that it becomes harder and harder for them to lose. Among the other casualties of this process would be American civil society as we have known it. Like other apocalyptic visions, this one is pessimistic, perhaps too much so. On the other hand, there is much to be pessimistic about.

This theme in the book is really just a continuation of Murray’s prior Coming Apart, about the dissolution of small town America, into a geographically divided country. However, I don’t think TBC was really saying that a truly meritocratic system would result in a caste. Meritocracy by itself does not produce castes, it only does that together with movements of people and various institutions supporting this.

The ethnic gaps are of course real. It’s always infuriating when books confidently, morally self-righteously repeats these falsehoods. It’s not difficult to check because pretty much every scientific source says the same thing about the gaps and their reality.

Herrnstein and Murray are wrong to imply that meritocracy will eventually lead to a static society. They repeat a common mistake in the nature–nurture debate: assuming that nature is a more conservative force than nurture. The truth is the opposite: it is nature rather than nurture that is the great disruptor. Parents can’t guarantee that their children will be exactly like them because of the unpredictable dance of the chromosomes through genetic recombination and the statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean (the tendency of tall children to have slightly shorter children and short people to have slightly taller children).

In actual fact, regression towards the mean is explicitly discussed in TBC to make the exact same point:

This differentiation by cognitive ability did not coalesce into cognitive classes in premodern societies for various reasons. Clerical celibacy was one. Another was that the people who rose to the top on their brains were co-opted by aristocratic systems that depleted their descendants’ talent, mainly through the mechanism known as primogeniture. Because parents could not pick the brightest of their progeny to inherit the title and land, aristocracies fell victim to regression to the mean: children of parents with above-average IQs tend to have lower IQ s than their parents, and their children’s IQs are lower still. Over the course of a few generations, the average intelligence in an aristocratic family fell toward the population average, hastened by marriages that matched bride and groom by lineage, not ability.

–

The Bell Curve is wrong to focus on group rather than individual differences for two reasons. The first is that group differences can easily be accounted for by environmental differences: Herrnstein and Murray concede that the environment accounts for anything from 20 to 60 per cent of IQ differences but then fail to acknowledge the fact that environmental differences can account for average differences in test results: African-Americans live, on average, in much poorer neighbourhoods than whites. The second is that group differences are far smaller than individual differences. Herrnstein and Murray focus on the small difference between averages in various populations. But the most striking fact revealed by IQ tests is the huge difference within populations. The differences that matter are the differences between individuals rather than the (purported) differences between groups.

TBC does not focus on group differences. Literally, the first 12 chapters are only about White people (269 pages of 553). There are two chapters about ethnic differences, running less than 100 pages. There are two more chapters about affirmative action, which concern group differences indirectly. Mostly, the message of TBC is that we need to learn to live together despite being different in intelligence and race. The last chapter is titled “A place for everyone”.

Race differences cannot easily be accounted for by environmental differences. In fact, Jensen’s variance argument along with current estimates of the influence of genetics shows this to be impossible. Anyone familiar with the debate knows this problem, Flynn wrote about it back in 1980, Jensen made his argument in detail in 1973. Race differences are not small. An effect size of 1.00 d (Black-White IQ gap) is very large in social science.

Conclusions

This book is an enjoyable read of various historical facts that lead to a more efficient and fair society. Meritocracy is indeed great for almost everybody. It is a shame that the author felt the need to hammer on The Bell Curve in the conclusion. It’s almost a ritual. We may speculate this was done out of ignorance, in which case it casts doubt on the rest of the book’s scholarship. How could the author have made these statements if he had read the book or any other mainstream book on intelligence? (e.g. Haier, Rindermann). Alternatively, it was done to “punch right”, so that no reviewer would attack the book on grounds that it didn’t sufficiently repudiate The Bell Curve, racism etc. By throwing a few punches in that direction, the author may have saved himself from enduring something similar to what Murray had to endure the last 30 years. The morality of such lies, however, is very dubious. Live not by lies.