Given the interest in the recent estimates of Scott Alexander’s, Gwern’s etc. IQs on Twitter, I thought it might be informative and entertaining to carry out a real survey (defined as me polling random people on Twitter). So we made a survey, which you might take here. This post explains the results based on the n=584 people who contributed data.

First, we need to talk about the dirty parts. Some people decided it was fun to troll the survey. Naturally, I am the target:

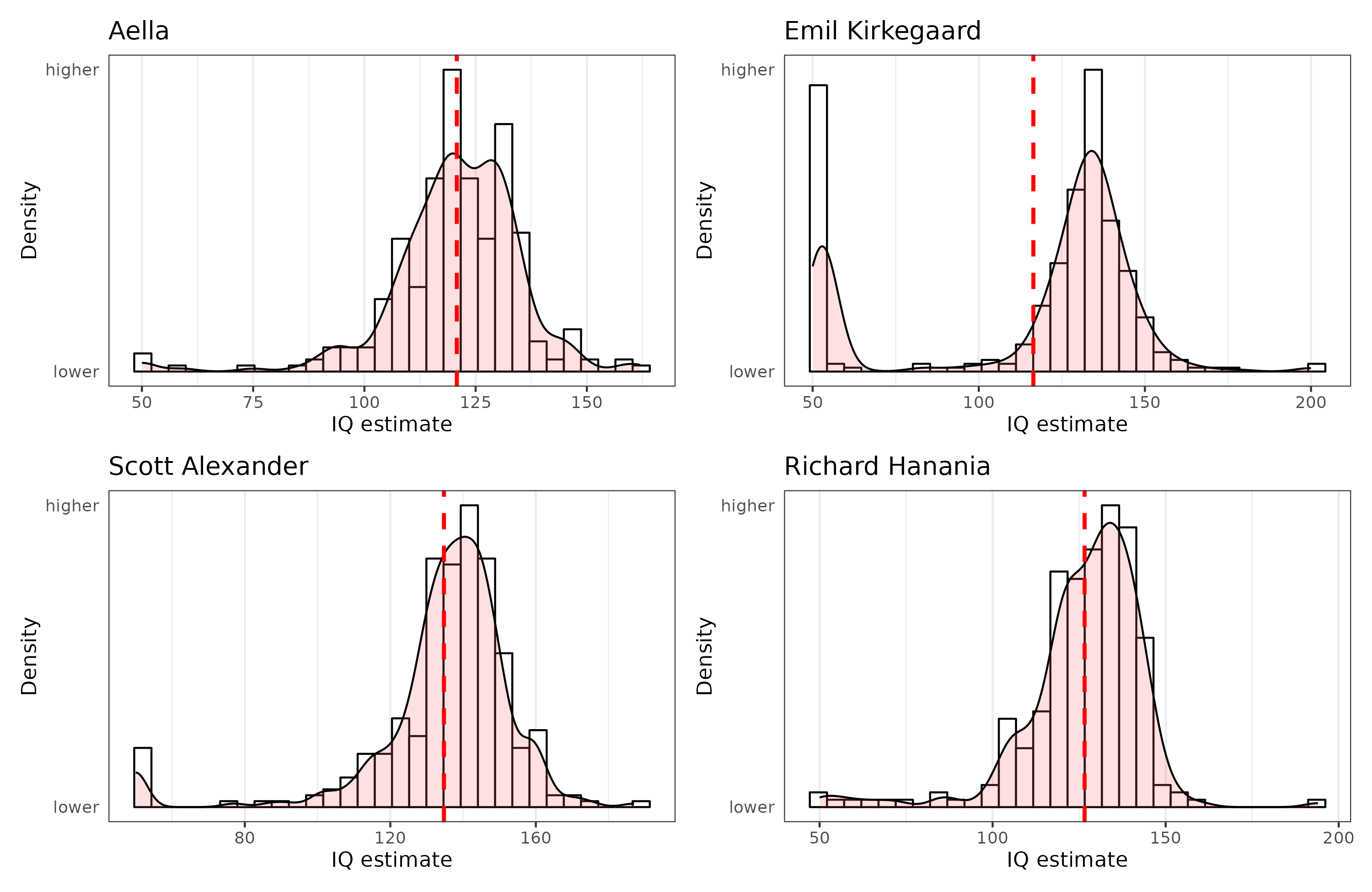

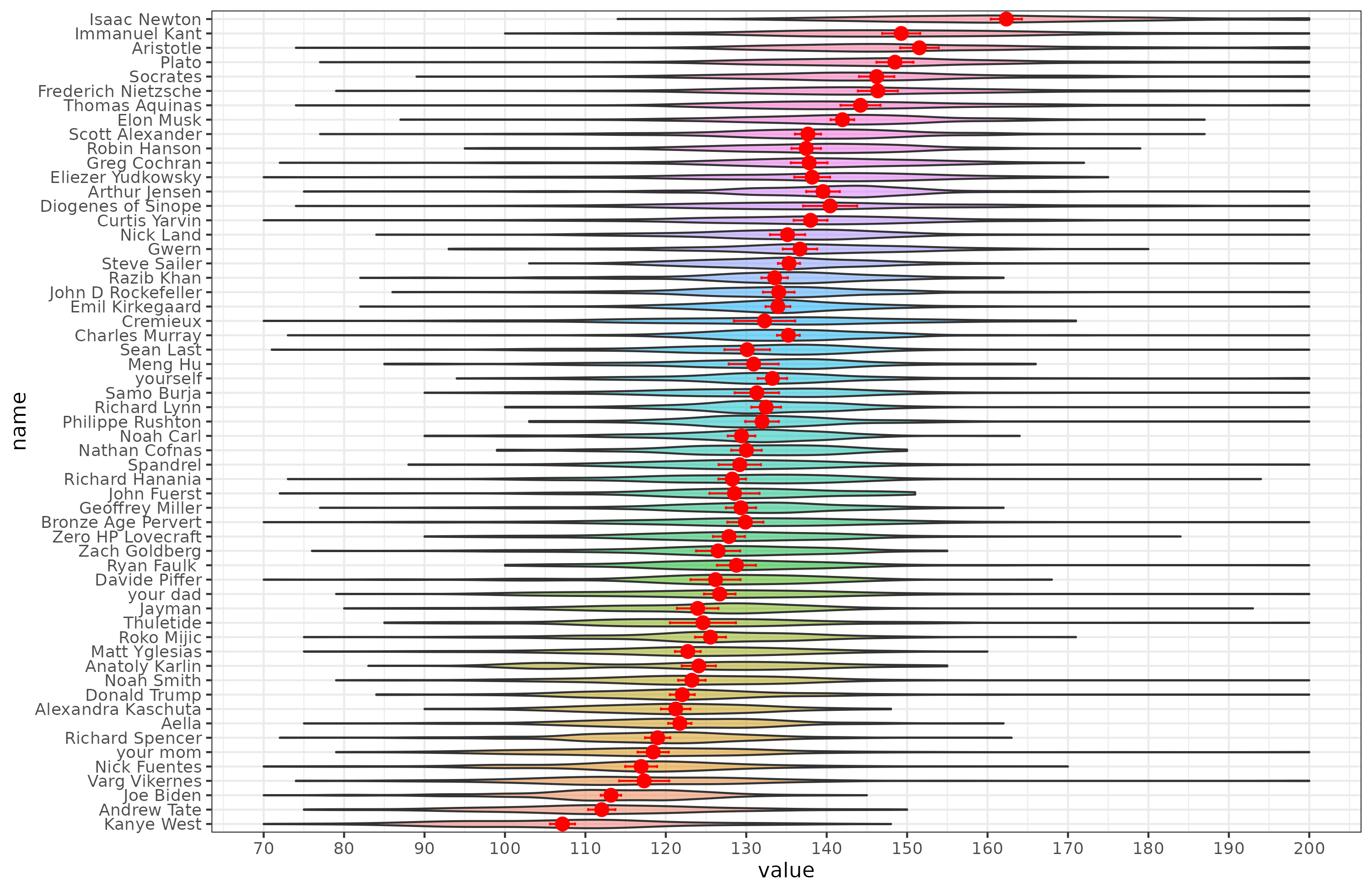

These people appear to have filled in very low IQ estimates for people they don’t like, as can be seen for mine above and for Scott Alexander to a lesser extent. But as data for Aella and Richard Hanania shows, every target (person being rated) has some proportion of very low estimates. I took a simple approach to this problem and deleted all the estimates below 70. After this, the distributions are mostly free of troll data, but I also use medians instead of means to further reduce the effect. Here’s the overall results, sorted by median IQ estimate:

Poor Kanye West takes the bottom position with a median estimate of 108 IQ, while Isaac Newton takes the top spot with 160. Now, it can be said we forgot certain people. A case could be made for Steven Pinker, Albert Einstein, Obama, Michael Woodley, and so on.

Glancing over the results, we might perceive a somewhat conservative bias in that the leftists or other non-conservatives are relatively down-rated (Aella, Noah Smith, Matt Yglesias, Joe Biden). It’s not really something we can scientifically study here given that there’s only really 3 left-wing people included (Aella is a sex worker). But other people who are definitely not left-wing are also relatively low ranked such as Andrew Tate and Richard Spencer. Overall, the estimate for the intellectuals is about 135 and the entire group’s median is 131. This sounds cool until you realize that the survey takers rated themselves, on median, at 132. Curiously, they rated their fathers at 127 and mothers at 118. So maybe this shows that people overestimate their father’s intelligence, or that the mostly male survey takers overestimate their fathers, or maybe that there is really a 9 IQ gap between their parents (or some combination of these).

On the quantitative side, the ratings are extremely reliable. The aggregate intraclass correlation reliability is 1.00, but each rater’s ‘reliability’ is only .31. This is however a substantial underestimate due to the various bad actors. Here’s the distribution of each rater’s correlation with the median estimates from the other raters:

So we see that only a few people had poor agreement with others, and many of these were literally reversed, suggesting they deliberately estimated people opposite of what they thought to mess up the results. We have seen this kind of thing in stereotype research a number of times (usually by people who vote for green parties). The median subject, however, had a correlation with the other raters of .77, which is rather high! As such, there seems to be broad agreement about who is smart and not in the above list of people and probably more generally.

Are these for real?

Is Scott really just 140 IQ? Is Gwern 136? We don’t really know, but the estimates are probably measuring something that has to do with their real levels of intelligence. The targets suffer from extreme range restriction as most people are in the 130’s area, so a correlation with IQ scores for these people wouldn’t be particularly informative (recall, n = 54). However, it is worth saying a few words about the relationship between genius and intelligence. The above individuals are generally characterized by extreme creative outputs in the sense of writing or otherwise producing more cultural content than most other people do. Certainly, this has something to do with their intelligence levels, but also generally, differences between intellectuals and typical 130+ IQ people have relatively little to do with intelligence because there just isn’t that much variation further out. Instead, differences in output quality and quantity between you and Scott Alexander, for instance, have a lot more to do with Galton’s ‘triple event’:

The particular meaning in which I employ the word ability, does not restrict my argument from a wider application; for, if I succeed in showing—as I undoubtedly shall do—that the concrete triple event, of ability combined with zeal and with capacity for hard labour, is inherited, much more will there be justification for believing that any one of its three elements, whether it be ability, or zeal, or capacity for labour, is similarly a gift of inheritance.

As usual, Arthur Jensen picked up the mantle and provided a good discussion of this multiplicative model of creative achievement (Jensen 1996: Giftedness and genius: Crucial differences):

I will argue that exceptional achievement is a multiplicative function of a number of different traits, each o f which is normally distributed, but which in combination are so synergistic as to skew the resulting distribution of achievement. An extremely extended upper tail is thus produced, and it is within this tail that genius can be found. An interesting two-part question then arises: how many different traits are involved in producing extraordinary achievement, and what are they? The musings that follow provide some conjectures that can be drawn on to answer this critical question.

Jensen summarizes them as:

Genius = High Ability X High Productivity X High Creativity

The theoretical underpinnings o f these three ingredients are:

—Ability = g = efficiency of information processing

—Productivity = endogenous cortical stimulation

—Creativity = trait psychoticism

I suggest that to explain the relative productivity of someone like Scott Alexander (or myself) in contrast with our many friends with similar intelligence levels, one should look towards the other two factors above. The last one usually results in mental illness in the family, especially psychosis (fittingly, my paternal grandmother was a schizophrenic). For those interested in much, much more on the origins of genius, read Hans Eysenck’s fantastic book Genius: The natural history of creativity (1995). I wrote a long review of it a few years ago.