I don’t think Malcolm Gladwell has been debunked hard enough, so here’s my contribution towards that goal. For Steven Pinker’s take, see here. Gladwell is essentially a story teller, and while he doesn’t directly make stuff up, as far as we know (unlike e.g. Jonah Lehrer), he plays fast and loose with sources.

Some years ago, someone told me about Gladwell making some claims regarding the so-called threshold of IQ utility hypothesis:

But there’s a catch. The relationship between success and IQ works only up to a point. Once someone has reached an IQ of somewhere around 120, having additional IQ points doesn’t seem to translate into any measurable real-world advantage.*

“It is amply proved that someone with an IQ of 170 is more likely to think well than someone whose IQ is 70,” the * The “IQ fundamentalist” Arthur Jensen put it thusly in his 1980 book Bias in Mental Testing (p. 113): “The four socially and personally most important threshold regions on the I Q scale are those that differentiate with high probability between persons who, because of their level of general mental ability, can or cannot attend a regular school (about IQ 50), can or cannot master the traditional subject matter of elementary school (about IQ 75),can or cannot succeed in the academic or college preparatory curriculum through high school (about IQ 105), can or cannot graduate from an accredited four-year college with grades that would qualify for admission to a professional or graduate school (about IQ 115). Beyond this, the IQ level becomes relatively unimportant in terms of ordinary occupational aspirations and criteria of success. That is not to say that there are not real differences between the intellectual capabilities represented by IQs of 115 and 150 or even between IQs of 150 and 180. But IQ differences in this upper part of the scale have far less personal implications than the thresholds just described and are generally of lesser importance for success in the popular sense than are certain traits of personality and character.”

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Hachette UK.

Seems convincing? Well, not so fast. If we actually read Jensen 1980 (an awesome book), which I was doing at the time I heard this claim, here is Jensen in full:

Although IQs are an interval scale, the practical, social, economic, and career implications of different IQs most certainly do not represent equal intervals. Again, this is not a fault of the IQ scale, but is the result of personal and societal values and demands. The implications and consequences of, say, a 30-point IQ difference is more significant between IQs of 70 and 100 than between IQs of 130 and 160. The importance of a given difference depends not only on its magnitude, but on whether or not it crosses over any of the social, educational, and occupational thresholds of IQ. To be sure, these thresholds are statistical and represent only differing probabilities for individuals’ falling on either side of the threshold. But the differential probabilities are not negligible. Such probabilistic thresholds of this type occur in different regions of the IQ scale, not by arbitrary convention or definition, but because of the structure of the educational and occupational systems of modem industrial societies and their correlated demands on the kind of cognitive ability measured by IQ tests.

The four socially and personally most important threshold regions on the IQ scale are those that differentiate with high probability between persons who, because of their level of general mental ability, can or cannot attend a regular school (about IQ 50), can or cannot master the traditional subject matter of elementary school (about IQ 75), can or cannot succeed in the academic or college preparatory curriculum through high school (about IQ 105), and can or cannot graduate from an accredited four-year college with grades that would qualify for admission to a professional or graduate school (about IQ 115). Beyond this, the IQ level becomes relatively unimportant in terms of ordinary occupational aspirations and criteria of success. That is not to say that there are not real differences between the intellectual capabilities represented by IQs of 115 and 150 or even between IQs of 150 and 180. But IQ differences in this upper part of the scale have far less personal implications than the thresholds just described and are generally of lesser importance for success in the popular sense than are certain traits of personality and character.

The social implications of exceptionally high ability and its interaction with the other factors that make for unusual achievements are considerably greater than the personal implications. The quality of a society’s culture is highly determined by the very small fraction of its population that is most exceptionally endowed. The growth of civilization, the development of written language and of mathematics, the great religious and philosophic insights, scientific discoveries, practical inventions, industrial developments, advancements in legal and political systems, and the world’s masterpieces of literature, architecture, music and painting, it seems safe to say, are attributable to a rare small proportion of the human population throughout history who undoubtedly possessed, in addition to other important qualities of talent, energy, and imagination, a high level of the essential mental ability measured by tests of intelligence. [pp.113ff ]

…

IQ Not a Threshold Variable for Scholastic Achievement. Note that the regression line of achievement on intelligence in Figure 8.1 is linear throughout the entire range of IQ scale. This is typical of the findings of the many studies that have investigated the form of the regression of achievement on IQ. The findings are unequivocal. There is no point on the IQ scale below which or above which IQ is not positively related to achievement. This means that IQ does not act as a threshold variable with respect to scholastic achievement, as has been suggested by some of the critics of IQ tests, for example, McClelland (1958, p. 13), who wrote: “ Let us admit that morons cannot do good school work. But what evidence is there that intelligence is not a threshold type of variable; that once a person has a certain minimal level of intelligence, his performance beyond that point is uncorrelated with ability?” There is plenty of evidence that this is not the case. The evidence is overwhelming that scholastic achievement increases linearly as a function of IQ throughout the entire range of the IQ scale so long as scholastic achievement itself is measured on a continuous scale unrestricted by the artifacts of ceiling or floor effects due to the achievement tests not including simple enough or advanced enough items. Even items such as “ can button shirt,” “ can tie own shoe laces,” “can eat with a fork,” and “ can say own name” are achievements that are positively correlated with IQ at the lower end of the intelligence scale. At the other end of the scale, for IQs of 140 and above, there are still achievement differences related to IQ, as can be seen by contrasting the typical school-age intellectual achievements of Terman’s (1925) gifted group with IQs above 140 (the top 1 percent) with Hollingworth’s (1942) even more highly gifted group with IQs above 180. Some of the differences in the intellectual achievements even among children in the IQ range from 140 to 200 are quite astounding. Over fifty years ago, Hollingworth and Cobb (1928) strikingly demonstrated marked differences in a host of scholastic achievements between a group of superior children clustering around 146 IQ and a very superior group clustering around IQ 165. The achievement differences between these groups are about as great as between groups of children of IQ 100 and IQ 120. It is also noteworthy that the superior (IQ 146) and very superior (IQ 165) groups do not differ in the least in ratings of the quality of their home backgrounds. [pp. 319ff]

[my underlining]

- Arthur Jensen. 1980. Bias in Mental Testing.

In conclusion:

- Jensen was only talking about socially significant thresholds in a statistical sense. A 150er IQ has a lot higher chance to graduate college than a 120 IQer, the difference being much higher if we look at PHDs instead of mere bachelor degrees.

- Jensen plants the seed for the right tail model of human progress, currently being promoted by Rindermann et al under the names of “cognitive elite”, “intellectual class” or “smart fraction” (Griffe du Lion, 2002). Probably someone had this idea before Jensen, but I don’t know. Cattell and Terman probably.

- Gladwell selectively quotes Jensen in misleading way to suggest quite the opposite of what Jensen actually wrote.

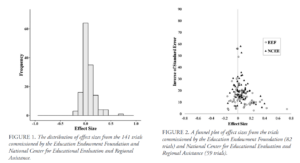

Here’s two recent studies of right tail differences in intelligence and achievements:

- Lubinski, D. (2016). From Terman to today: A century of findings on intellectual precocity. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 900-944.

- Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Hyytinen, A., & Toivanen, O. (2017). The social origins of inventors (No. w24110). National Bureau of Economic Research. (See also Steve Hsu coverage)

One could also utilize the huge Project TALENT dataset (n = 440k) to examine this, but one has to apply and get the restricted longitudinal follow-up data (why is it restricted when the first wave data is not? no idea!). Something I’ve been meaning to do, but haven’t got done.

Turns out Jonathan Wai already did the Project TALENT analysis, at least some of them.

- Wai, J. (2014). Experts are born, then made: Combining prospective and retrospective longitudinal data shows that cognitive ability matters. Intelligence, 45, 74-80.

2019 January update

Trannyporno found some more studies:

-

Coward, W. M., & Sackett, P. R. (1990). Linearity of ability-performance relationships: A reconfirmation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(3), 297.

-

Arneson, J. J., Sackett, P. R., & Beatty, A. S. (2011). Ability-performance relationships in education and employment settings: Critical tests of the more-is-better and the good-enough hypotheses. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1336-1342.

-

Coyle, T. R. (2015). Relations among general intelligence (g), aptitude tests, and GPA: Linear effects dominate. Intelligence, 53, 16-22.

2020 January update

-

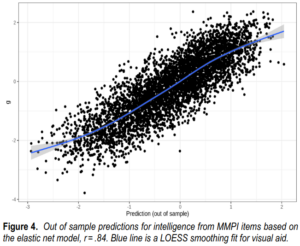

Gensowski, M., Heckman, J., & Savelyev, P. (2011). The effects of education, personality, and IQ on earnings of high-ability men. Unpublished manuscript.

- Via Hsu blog. Note that it shows increasing returns for higher IQ for income/earnings. This is a common finding, perhaps explained by extreme comparative advantage of such individuals.