Most people people my age know about a documentary called Supersize me! from 2004.

The story of it goes like this:

As the film begins, Spurlock is in physically above average shape according to his personal trainer. He is seen by three physicians (a cardiologist, a gastroenterologist, and a general practitioner), as well as a nutritionist and a personal trainer. All of the health professionals predict the “McDiet” will have unwelcome effects on his body, but none expected anything too drastic, one citing the human body as being “extremely adaptable”. Prior to the experiment, Spurlock ate a varied diet but always had vegan evening meals to accommodate his girlfriend, Alexandra, a vegan chef. At the beginning of the experiment, Spurlock, who stood 6 feet 2 inches (188 cm) tall, had a body weight of 185 pounds (84 kg).

Experiment Spurlock followed specific rules governing his eating habits:

He must fully eat three McDonald’s meals per day: breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

He must consume every item on the McDonald’s menu at least once over the course of the 30 days (he managed this in nine days).

He must only ingest items that are offered on the McDonald’s menu, including bottled water. All outside consumption of food is prohibited.

He must Super Size the meal if offered, but he cannot request to Super Size on his own.

He will attempt to walk about as much as a typical United States citizen, based on a suggested figure of 5,000 standardized distance steps per day,[13] but he did not closely adhere to this, as he walked more while in New York than in Houston.On February 1, Spurlock starts the month with breakfast near his home in Manhattan, where there is an average of four McDonald’s locations (and 66,950 residents, with twice as many commuters) per square mile (2.6 km²). He aims to keep the distances he walks in line with the 5,000 steps (approximately two miles) walked per day by the average American.

Day 2 brings Spurlock’s first (of nine) Super Size meal, at the McDonald’s on 34th Street and Tenth Avenue, which is a meal made of a Double Quarter Pounder with Cheese, Super Size French fries, and a 42-ounce Coca-Cola, which took him 22 minutes to eat. He experiences steadily increasing stomach discomfort during the process, and then finally vomits in the McDonald’s parking lot.

After five days Spurlock has gained 9.5 pounds (4.3 kg) (from 185.5 to about 195 pounds). It is not long before he finds himself experiencing depression, and he claims that his bouts of it along with lethargy, and headaches could be relieved by eating a McDonald’s meal. His general practitioner describes him as being “addicted”. At his second weigh-in, he had gained another 8 pounds (3.6 kg), putting his weight at 203.5 pounds (92.3 kg). By the end of the month he weighs about 210 pounds (95 kg), an increase of about 24.5 pounds (about 11 kg). Because he could only eat McDonald’s food for a month, Spurlock refused to take any medication at all. At one weigh-in, Spurlock lost 1 lb. from the previous weigh-in, and a nutritionist hypothesized that he had lost muscle mass, which weighs more than an identical volume of fat. At another weigh-in, a nutritionist said that he gained 17 pounds (7.7 kg) in 12 days.

Spurlock’s then-girlfriend, Alexandra Jamieson, attests to the fact that Spurlock lost much of his energy and sex drive during his experiment. It was not clear at the time whether or not Spurlock would be able to complete the full month of the high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet, and family and friends began to express concern.

On Day 21, Spurlock has heart palpitations. His internist, Dr. Daryl Isaacs, advises him to stop what he is doing immediately to avoid any serious health problems. He compares Spurlock with the protagonist played by Nicolas Cage in the movie Leaving Las Vegas, who intentionally drinks himself to death in a matter of weeks. Despite this warning, Spurlock decides to continue the experiment.

On March 2, Spurlock makes it to day 30 and achieves his goal. In thirty days, he has “Supersized” his meals nine times along the way (five of which were in Texas, four in New York City). His physicians are surprised at the degree of deterioration in Spurlock’s health. He notes that he has eaten as many McDonald’s meals as most nutritionists say the ordinary person should eat in eight years (he ate 90 meals, which is close to the number of meals consumed once a month in an eight-year period).

Findings The documentary’s end text states that it took Spurlock five months to lose 20.1 pounds (9.1 kg) and another nine months to lose the last 4.5 pounds (2.0 kg). His then-girlfriend Alex, now his ex-wife, began supervising his recovery with her “detox diet”, which became the basis for her book, The Great American Detox Diet.[14]

The movie ends with a rhetorical question, “Who do you want to see go first, you or them?” This is accompanied by a cartoon tombstone, which reads “Ronald McDonald (1954–2012)”, which originally appeared in The Economist in an article addressing the ethics of marketing to children.[15]

A short epilogue was added to the film. It showed that the salads can contain even more calories than burgers if the customer adds liberal amounts of cheese and dressing prior to consumption. Also, it described McDonald’s discontinuation of the Super Size option six weeks after the movie’s premiere, as well as its recent emphasis on healthier menu items such as salads, and the release of the new adult Happy Meal. McDonald’s denied that these changes had anything to do with the film.[16]

So it seems like it basically shows that McDonald’s food is so unhealthy that just eating it alone is sufficient to cause severe issues. But then again, there’s also some other people:

In his reply documentary Fat Head, Tom Naughton “suggests that Spurlock’s calorie and fat counts don’t add up” and noted Spurlock’s refusal to publish the Super Size Me food log. The Houston Chronicle reports: “Unlike Spurlock, Naughton has a page on his Web site that lists every item (including nutritional information) he ate during his fast-food month.”[25]

After eating exclusively at McDonald’s for one month, Soso Whaley said, “The first time I did the diet in April 2004, I lost 10 pounds (going from 175 to 165) and lowered my cholesterol from 237 to 197, a drop of 40 points.” Of particular note was that she exercised regularly and did not insist on consuming more food than she otherwise would. Despite eating at only McDonald’s every day, she maintained her caloric intake at around 2,000 per day.[26]

After John Cisna, a high school science teacher, lost 60 pounds while eating exclusively at McDonald’s for 180 days, he said, “I’m not pushing McDonald’s. I’m not pushing fast food. I’m pushing taking accountability and making the right choice for you individually… As a science teacher, I would never show Super Size Me because when I watched that, I never saw the educational value in that… I mean, a guy eats uncontrollable amounts of food, stops exercising, and the whole world is surprised he puts on weight? What I’m not proud about is probably 70 to 80 percent of my colleagues across the United States still show Super Size Me in their health class or their biology class. I don’t get it.”[27]

As a counterpoint, the film features interviews with Big Mac aficionado Don Gorske, who eats an average of 2 Big Macs a day, yet maintains his weight and cholesterol.

OK, so this is one anecdote that was filmed vs. some other ones that weren’t. Both are quite likely cherry picked. What to believe? Let’s ask science! Fortunately for us, someone did a real experiment back in… 2006? New Scientist has the write-up ‘Supersize me’ revisited – under lab conditions (non-gated):

If you had bumped into nursing student Adde Karimi last September, he probably wouldn’t have had much time to stop and chat. He was too busy stuffing his face with burgers, cola and milkshakes. It takes a lot of planning to get 6600 calories of junk food down you in a day, he explains. If you are not a born glutton, serious overeating also requires a high level of commitment. Karimi’s motivation was commendable. “I did it because I wanted to hate this type of food,” he says. He also did it for science.

Even if you have never tried to cure your cravings for fast food by overdosing on it, you may be getting a sense of déjà vu. That’s because Karimi was a volunteer in an experiment based on the 2004 documentary Super Size Me. In the movie, film-maker Morgan Spurlock spent 30 days eating exclusively at McDonald’s, never turning down an offer to “supersize” to a bigger portion, and avoiding physical exertion. Karimi followed a similar regime, gorging himself on energy-dense food and keeping exercise to a minimum.

That is pretty much where the similarities end, though. By the end of Spurlock’s McDonald’s binge, the film-maker was a depressed lardball with sagging libido and soaring cholesterol. He had gained 11.1 kilograms, a 13 per cent increase in his body weight, and was on his way to serious liver damage. In contrast, Karimi had no medical problems. In fact, his cholesterol was lower after a month on the fast food than it had been before he started, and while he had gained 4.6 kilos, half of that was muscle.

The brains behind this particular experiment is Fredrik Nyström from Linköping University in Sweden. In the past year he has put 18 volunteers through his supersize regime, and what fascinates him most is the discovery that there was such huge variation in their response to the diet. Some, like Karimi, took it in their stride. Others suffered almost as much as Spurlock, with one volunteer taking barely two weeks to reach the maximum 15 per cent weight gain allowed by the ethics committee that had approved the study. We are used to being told that if we are overweight the problem is simply too much food and too little exercise, but Nyström has been forced to conclude that it isn’t so straightforward. “Some people are just more susceptible to obesity than others,” he says.

This write-up, though interesting, is very light on quantitative details. So I went to Fredrik Nyström’s page, and then his scholar to figure out which study this is based on. It proved difficult because, well:

- Kechagias, S., Ernersson, Å., Dahlqvist, O., Lundberg, P., Lindström, T., Nystrom, F. H., & Fast Food Study Group. (2008). Fast-food-based hyper-alimentation can induce rapid and profound elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase in healthy subjects. Gut, 57(5), 649-654.

- Reply: Johnston, R. D., Aithal, G. P., Ryder, S. D., & MacDonald, I. A. (2009). Fast-food hyper-alimentation and exercise restriction in healthy subjects. Gut, 58(3), 469-470.

- Leinhard, O. D., Johansson, A., Rydell, J., Kihlberg, J., Smedby, Ö., Nyström, F. H., … & Borga, M. (2009). Quantification of abdominal fat accumulation during hyperalimentation using MRI. In Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med (Vol. 17).

- Erlingsson, S., Herard, S., Leinhard, O. D., Lindström, T., Länne, T., Borga, M., … & Fast Food Study Group. (2009). Men develop more intraabdominal obesity and signs of the metabolic syndrome after hyperalimentation than women. Metabolism, 58(7), 995-1001.

- Danielsson, A., Fagerholm, S., Öst, A., Franck, N., Kjolhede, P., Nystrom, F. H., & Strålfors, P. (2009). Short-term overeating induces insulin resistance in fat cells in lean human subjects. Molecular Medicine, 15(7), 228-234.

- Ernersson, Å., Lindström, T., Nyström, F. H., & Frisman, G. H. (2010). Young healthy individuals develop lack of energy when adopting an obesity provoking behaviour for 4 weeks: a phenomenological analysis. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 24(3), 565-571.

- Åstrand, O., Carlsson, M., Nilsson, I., Lindström, T., Borga, M., & Nyström, F. (2010). Weight gain by hyperalimentation elevates C-reactive protein levels but does not affect circulating levels of adiponectin or resistin in healthy subjects. European journal of endocrinology, 163(6), 879-885.

Many of these have ominous titles, compared to the relatively worry-free write-up in New Scientist. So which one is it? McDonald’s dangerous or not? Let’s check the first paper, that’s the first one, and the one cited the most (222 citations):

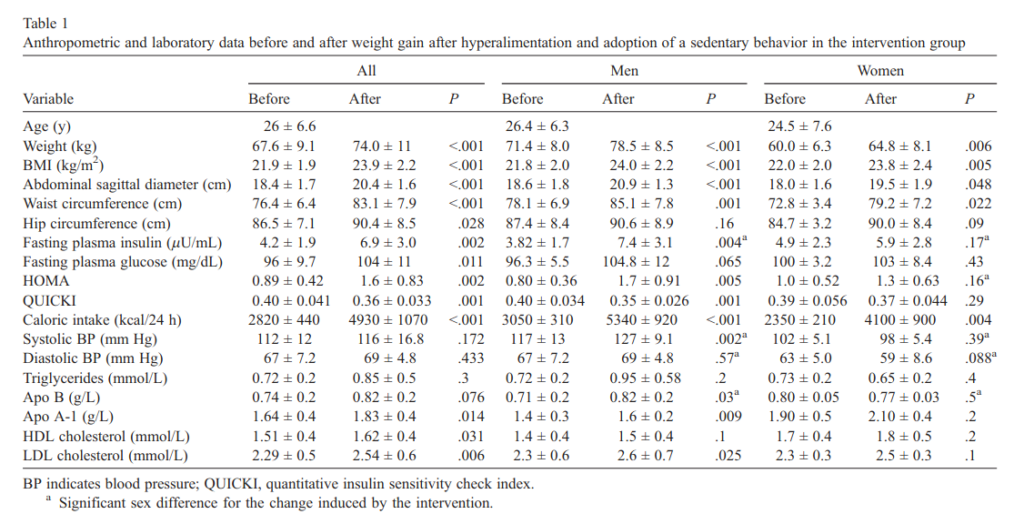

Can you spot the profound? As a matter of fact, their study could not even detect the weight change for intervention vs. controls (p = .20), only for intervention pre-post (p < .001). (If you are wondering why this can be, it is because self-controls using longitudinal designs offer much more statistical precision for same sample size.) The changes of note are mainly concerned with obesity/fat, which is not to surprising given the excess calories. The biometrics are more interesting, but hardly profound. E.g. albumin was 4.1 before diet, 4.0 after, and controls were 4.3 after, p = .002, but the change is unremarkable.

OK, let’s check the second one, the one finding more evidence for metabolic syndrome in men:

These are the pre-post tests by sex. As readers may recall, one cannot just compare the p values (columns 6 vs. 9) and when they differ by p < .05 status, conclude there is a sex interaction (works differently by sex). One has to conduct an explicit test for this (interaction test). The authors did just that (the paired t-test variant), it’s that one letter “a” that is seen 5 times. These are the measures where men and women’s pre-post differences were themselves different (presumably at p < .05). For instance men’s fasting plasma insulin about doubled from 3.82 to 7.40, but women’s went from 4.9 to 5.9. Overall, it looks like the authors are right in that obesity gain from fast food had a larger impact on men than women, even based on this n=18 study. Still, no one acquired any metabolic syndrome or anything. The study was actually set to terminate for subjects if they developed serious issues, and this didn’t happen for any subject.

My guess at what happened with this story is this: Researchers got excited by the Supersize Me documentary. They decide to try to run a real experiment. Somehow a journalist learns about this, maybe from a conference talk, and they do a nice interview article about one author’s real conclusions based on the study. The authors then later also need to publish papers based on this. Publishing an n=18 paper saying that “well, we had 18ish medical students eat fast food for a 4 weeks, and nothing much happened aside from some weight gain” would be hard to publish in a ‘good journal’. Where’s the story there? So the authors did the respectable ordinary scientific thing: they looked real hard at the data to find something to tell a more interesting story about. Then they split this into at least 6 studies and published them in different places to maximize the citation index gains.

In any case, I think the conclusion, weak as it is, is sufficient to show that the Supersize me documentary is dubious, or maybe even a hoax. Clearly, eating a lot of McDonald’s fast food (or Burger King etc.) is not really so unhealthy that there is serious health risk after a month. The other anecdotes and this study of 18 people showed that clearly. So what did Morgan Spurlock do? Who can say. We can think of benign explanations: maybe McD/Burger King changed their ingredients after 2004, or they differ between Sweden and USA, or Swedes are more naturally resistant to bad diets than English. Or maybe Spurlock engaged in a lot of creative freedom.

Humans are flexible omnivores, worry about other stuff than diet. There’s plenty of solid options.