There’s a really old study that is sometimes brought up. It was covered in depth by John Fuerst and HBD.info. I think Nisbett 2009 (Intelligence and how to get it, see this review by James Lee of GWAS fame) is the most comprehensive environmentalist case currently. He wrote:

Witty and Jenkins (1934, 1936) identified from a sample of black Chicago schoolchildren sixty-three with IQs of 125 or above and twenty-eight with IQs of 140 or above. On the basis of their self-reports about ancestry, the investigators classified the children into the four categories of Europeanness just described. The children with IQs of 125 or above, as well as those with IQs of 140 or above, had slightly less European ancestry than the best estimate for the American black population as a whole at the time. This study was not ideal. It would have been better to compare the degree of European ancestry in high-IQ Chicago children to that of other black Chicago children rather than to the entire black population. But once again the results are consistent with a model of zero genetic contribution to the black/white gap or, perhaps, a slight genetic advantage for Africans.

So it’s an extreme phenotype design, also occasionally used in GWASs. In fact, extreme phenotype designs are the norm in psychiatry if you accept the “abnormal is normal” model. The idea of these is that if you sample the tail of some distribution, you have a lot higher power to see a weak relationship to other variables. In this case, the claim is that European ancestry is related to intelligence per the genetic model. W&T tested this by checking whether very bright African American kids were higher in European ancestry. Since they didn’t have genetic tests, they used the cruder family history (why not measured skin color?). They compared this to values from a third study, found it wasn’t higher than average, and concluded that there is no relationship between European ancestry and intelligence in African Americans, and thus, the genetic model is wrong.

As a matter of fact, their reference value was wrong, and their results actually in line with genetic predictions. See the two cited posts for details. Still, no one has really shown this to be the case with modern datasets. That is, until now:

- Hu, M. (2022). More Evidence of an Association between European Ancestry and g among African Americans: An Analysis of a Nationally Representative Sample of American Youth. Mankind Quarterly, 62(3), Article 5. Free PDF

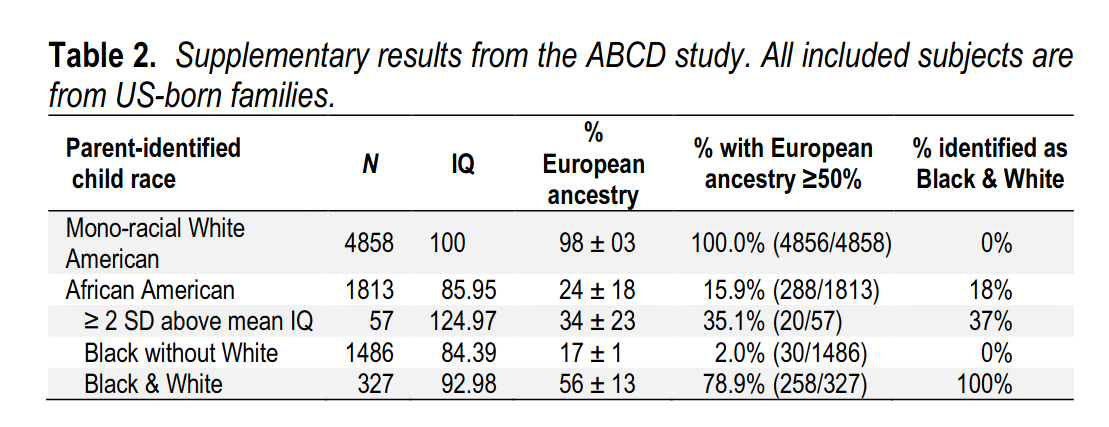

This report examines the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979 data. Self-reported European ancestry among Black Americans is found to have a positive yet moderate correlation with cognitive ability. Of the 2935 screener-identified African Americans, 53 had self-reported ancestry from a specific European ethnicity. This group had an advantage of .41d over African Americans who did not report any European ancestry. Consistent with previous results, the effect of European ancestry exhibited a positive correlation with subtest g-loadings. The findings were corroborated by results from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which used genetically assessed ancestry. In both cases, African Americans with more European ancestry were overrepresented, by a factor of two, in the right tail of the cognitive distribution.

The main results:

Hu notes:

The correlation between the g-loadings and point-biserial correlations, with both corrected for subtest reliability, was r = .40. This represents a relatively modest Jensen effect compared to various meta-analyses reporting a Jensen effect of r ~ .60 (Jensen, 1998, pp. 381-383; te Nijenhuis and van den Hoek, 2016; te Nijenhuis, van den Hoek & Willigers, 2017; te Nijenhuis, van den Hoek & Dragt, 2019). The general consensus indicates that the advantage of Black with European ancestry tends to be larger on more g-loaded tests. As an alternative test, we restrict the data to respondents with g scores two standard deviations or more above the African American mean. Out of the 99 individuals, three had reported European ancestry. This is equivalent to 3.03% of the sample, which is almost twice as high as the 1.81% in the total sample.

I think he paid too little attention to the very large sampling error here. These data are too weak to conclude that this method shows a weaker Jensen coefficient, as the confidence interval of that coefficient here would surely be very large (one can bootstrap it). In any case, we do the expected positive relationship, as was found also in PING, PNC, and ABCD.

I also don’t know why he didn’t just use the biserial correlation, the form of the latent correlation made for this pair of variable types (continuous + dichotomous). It doesn’t matter as the values will be identical, but then he wouldn’t have to do the Schmidt and Hunter adjustment.

Similarly, the ABCD results show that very bright African Americans do self-report substantially more White ethnicity than average, and indeed, they objective also have more European ancestry. This is as predicted by the genetic model. Hu concludes:

These results also suggest that the general approach proposed by Witty and Jenkins (1934) and Jenkins (1936) is valid: If ancestry is associated with intelligence among admixed populations, then the right tail should be overrepresented with more admixed individuals. This is what was found to be the case in both the NLSY79 and ABCD samples. Witty and Jenkins’ analysis, in contrast, suffered from failing to compare the ancestry of the selected group to the ancestry of the group from which it was selected. Instead, their comparison sample was a completely different and, moreover, socioeconomically selected one (Mackenzie, 1984), a point which is highly relevant since socioeconomic status positively correlated with European ancestry in admixed American groups (Kirkegaard, Wang & Fuerst, 2017). Had the authors made the correct comparison, they likely would have found results similar to the current ones. As it is, their data implies a reported mean European ancestry for their selected sample quite similar to the genetic ancestry of our intelligence-selected ABCD sample (30% vs. 34%; see Loehlin, Lindsay & Spuhler 1975, p. 130).

There is now a large body of evidence that European ancestry — whether self-reported, parent-reported, indexed by race-associated phenotype, or assessed genetically — is related to g in admixed American populations. These findings contradict previous narrative reviews (e.g., Colman, 2016; Nisbett, 2009) and suggest systematic bias in past narrative reviews. A systematic review of the 20th-century literature on admixture and cognitive ability is in order.

I think there is a small group working on the 20th century admixture results, which are pretty hereditarian too. Jensen summarized some of these already back in 1973 (Educability and Group Differences, chapter 9), but he omitted a lot of studies using Australian Aborigines, various admixed peoples in Latin America. Lynn summarizes many of these studies in his book Race differences in intelligence.