Undark magazine has a new piece out where a journalist expresses concern about people looking at their own DNA results: From a Fledgling Genetic Science, A Murky Market for Prediction. It’s the usual sort of thing where a journalist-instant-expert tells us ignorant readers what polygenic scores can and mostly can’t tell us. This is from the same magazine that ran a hit piece on Razib Khan back in 2017, Race, Science, and the Continuing Education of Razib Khan. But OK, it’s been 5 years, and the authors are different, so let’s not presume too much. On the other hand, the author is a Black guy called Ashley Smart who writes fairly typical Black victimization because racist bloggers pieces.

The piece is about the now-gone service impute.me that I covered back in 2020 and it’s successor start-up company. The site was the best in town in terms of where anyone could upload their genome from 23andme-like consumer genomics services free-of-charge and get a more complete set of genetic predictions (hundreds). You see, FDA famously cracked down on 23andme making their own predictions, so now the commercial players in the field are scared of trying too hard. This strangely leaves a market gap that non-profits can grab, even if they can’t make money of this. Danish researcher Lasse Folkersen did that and ran impute.me for 7 years:

Before joining Nucleus, Folkersen worked as a genetics expert at the Danish National Genome Center, and before that as a scientist with a psychiatric hospital based in Copenhagen. During evenings, he ran a website called Impute.me, where users could upload their raw genetic data from companies such as 23andMe or Ancestry and receive polygenic scores for any of hundreds of traits, calculated based on publicly available data from published genome-wide association studies. The service was free, though users who donated five dollars were promised spots at the front of the processing queue. As Folkersen recalled in an interview with Undark, when he started out in 2015, his was probably one of the only sites in the world where people could get polygenic risk scores. He estimates that during the seven years he ran the site, he processed around 100,000 unique genomes.

And that’s quite a large dataset! Unfortunately, Folkersen’s pet project has been taken over by a new start-up which will try to commercialize this idea. We will see how this goes, but such companies are dime a dozen and they don’t seem to be succeeding much. Here’s 23andme’s stock price, to give you the impression:

I mean, it is going better than Bitconnect, but you gotta wonder when they are going out of business, or perhaps big pharma will save them with another cash inflow.

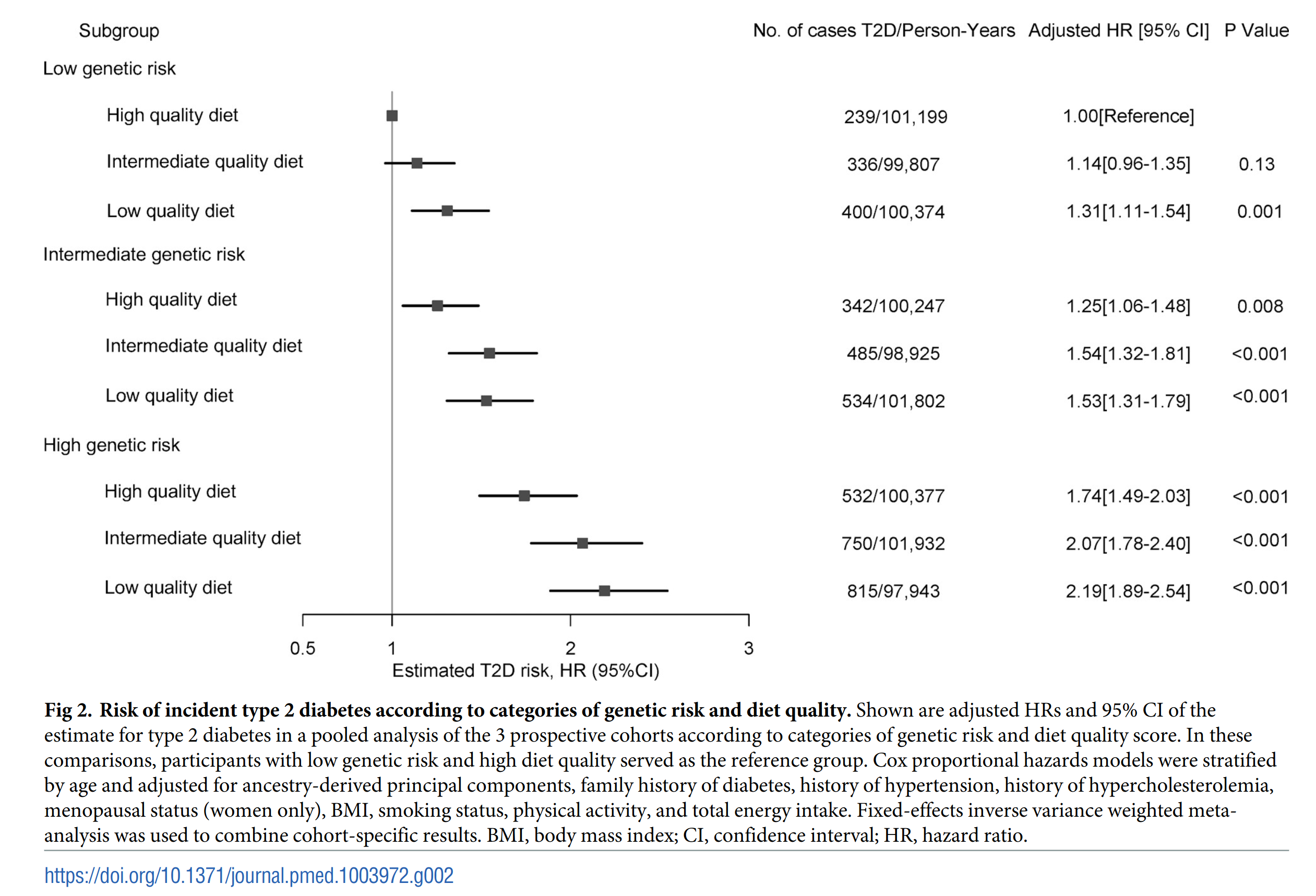

That aside, this new article is not so far off the mark when it comes to the science. It is true that current polygenic scores don’t really generate actionable insights. Personal genomics is a variant of personalized medicine, which is to a large extent useless for reasons I wrote about before earlier this year. Suppose you want to know about your risk for type 2 diabetes and whether you should take action. You could do any of several actions. You could look in the mirror or get on a scale. If it says a high number, it’s time to start the eat less diet. Alternatively, you could go to a doctor and get your biometrics measured, looking for signs of pre-diabetes. If there’s signs of danger, the action you need to do is still the same, and maybe cut sugary intake in particular. Or you could get a genetic test and look at your polygenic score for type 2 diabetes (T2D). In fact, the last is by far the worst option. The current polygenic scores have only moderate predictive validity, this 2022 study of 36k people found:

The polygenic scores were normally distributed (S1–S3 Figs). The age-adjusted HR for type 2 diabetes was 1.42 (95% CI 1.38, 1.46; I2 = 93.2%; P < 0.001) per 1 SD increase in the global polygenic score (S3 Table). In fully adjusted models, the global polygenic score was associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes with an HR of 1.29 (95% CI 1.25, 1.33; I2 = 88.4%; P < 0.001; per SD increase; Fig 1).

It doesn’t appear they reported values that can be more readily converted into familiar metrics. HR = hazard ratio, which is:

In survival analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) is the ratio of the hazard rates corresponding to the conditions characterised by two distinct levels of a treatment variable of interest. For example, in a clinical study of a drug, the treated population may die at twice the rate per unit time of the control population. The hazard ratio would be 2, indicating a higher hazard of death from the treatment.

So if you take a person and move them from 50th centile (average) genetic risk to 98th centile (+2 standard deviations), their per time risk of getting T2D is increased by 84% if you don’t add controls, and 58% if you do. I wasn’t able to find any way to convert this to a more regular metric, in fact, most advice given tried to avoid this. (It seems like the model itself should be able to get some kind of pseudo-R2 or partial pseudo-R2 for the variable, but they didn’t report it.) Whatever the current state of the art, it will be much worse than going to the bathroom and looking in the mirror and asking “do I look fat?”. A doctor’s test will give more precise information, but what is the point of this anyway? Everybody knows that being fat gives you diabetes so you don’t need a doctor’s test or genetic test to tell you this.

And yes, since you were wondering, the genetic risk also didn’t interact with any environmental (or “environmental”) variables, they were just additive:

As such, this massive study joins approximately every other GxE study published so far. That stuff is a waste of time, if there were any large effects of obvious utility we would have found them already.

Of course, the main point of a piece like the Undark one is to find some people who are worried or who will warn us about this or that:

Lewis told Undark that she worries the analyses will send customers rushing to their primary care providers to request unnecessary screening and tests.

In a 2021 paper, Brent Kious, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Utah, and his colleagues warned that polygenic scores for psychiatric traits could be easily misinterpreted by the public, and could contribute to harmful self-stigma and anxiety. The researchers called on the FDA to specifically prohibit direct-to-consumer polygenic scores for suicide risk, saying it was unclear whether there were any beneficial actions a person at elevated risk could take that would “offset the social and psychological harms of the tests themselves.”

Yet researchers typically have little say in how their data is used once they publish it. And for Daphne Martschenko, an assistant professor of biomedical ethics at Stanford University, some of the uses are troubling. Of particular concern, she said, are companies that have begun offering polygenic scores as part of their embryo screening services for in-vitro fertilization patients.

The answer, of course, is always more regulation-prohibition as decided by the experts (themselves, of course). And don’t forget about more research funding too.

The main selling point in the article is that the author found out that impute.me used to offer semi-secret intelligence predictions too, and yours truly had written about this:

The intelligence scores Folkersen offered clandestinely — at a page hidden from the Impute.me homepage but accessible with a URL or direct link. Responding on Reddit after a user seemed to express disappointment at being ranked in the zeroth percentile for the trait, Folkersen explained his rationale: “This is exactly the reason why the intelligence module is unlisted,” he wrote. “People can’t handle it if they get a low score because they somehow take it more personal than a real IQ test. They are wrong.”

Folkersen argued that an IQ test is a far more accurate prediction of intelligence than a polygenic score. Indeed, many scientists have said that polygenic scores aren’t equipped to predict individual outcomes for traits like intelligence. The genetic variants identified in a large 2018 GWAS for intelligence, published in Nature Genetics, could account for around 5 percent of the variance observed in studied populations of European ancestry, and part of that may reflect factors that are only indirectly related to genetics.

Despite Folkersen’s efforts to keep them discreet, Impute.me’s intelligence scores garnered attention in internet forums and message boards, at times providing fodder for racist diatribes. Emil Kirkegaard — a right-wing blogger who has argued for innate intellectual differences between races — described the intelligence scores as the “juicy parts” of the site.

Of course they are juicy. There’s a lot of interest in knowing your own intelligence, hence the 1000s of online IQ tests (most are shit though, but some are not). And now that one can make moderately accurate predictions based on DNA, a lot of people would like to know where they stand. Most people realize, of course, that if you want to know your intelligence, you should take tests (and only once and don’t cheat etc.). Looking at your genetic predictions will be a less accurate, but possibly more amusing method. The current polygenic scores for education can predict IQ perhaps with 16% of the variance for Europeans, corresponding to a correlation of about .40. You can think of that as the g-loading of the polygenic score. In other words, it’s better than taking a simple reaction time test (loading about .20), and much worse than taking a vocabulary or number series test (loading about .80). So the polygenic score will be on par with taking some mediocre short-term memory test that neuroscientists like to give to people.

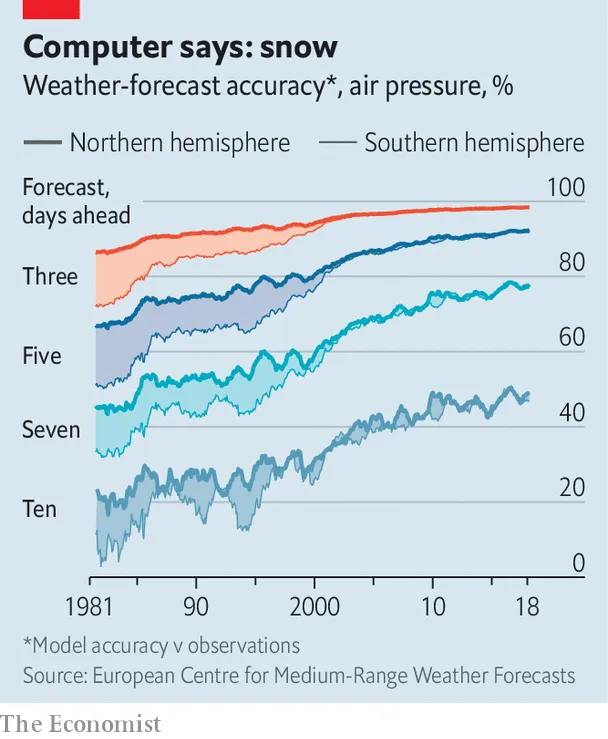

So while polygenic scores aren’t terribly useful on the individual level, they are quite useful for comparing groups of people, or for selecting embryos. When doing IVF, you have a forced choice. You must choose some embryo. Often there’s no particular reason to pick one over another based on their visual appearance. But genetic testing of embryos is possible, and in that case, one can pick the embryo with the best odds. And who wouldn’t? With the state of the art, the results won’t be amazing. You won’t be getting an Einstein every time. But you will be increasing your chances. And which parent wouldn’t want to decrease their future child’s chance of cancer, even if it’s only by 15%? Or increase the chance of getting a top 1% income by 15%? The utility of embryo selection will only increase as the models keep improving in accuracy. Think of how bad the weather forecasts used to be:

The theoretical limit for the predictive validity of polygenic scores is quite high. That value is simply the square root of the heritability (which is the correlation between the genetic potential and their phenotype). In case of type 2 diabetes, this 2023 meta-analysis of twin studies finds a best estimate of 72%. In other words, the correlation between a perfect (true) polygenic score and your real risk is r = .85. That’s much better than what the doctor’s visit can offer I would guess. If your parents find out that you are 95% centile on such a predictor, it would surely be wise to try extra hard to avoid diabetes causing modifiable factors. In terms of human diseases, we could radically decrease their prevalence (for specific age groups) if we applied rigorous genetic selection for a few generations with decent genetic models. What are we waiting for? These nay-sayer pieces aren’t helping, unless their pessimism inspires people to do better.