This is a natural follow-up to my prior post about fertility, and how cities (or population density in some sense) cause fertility to decline. In fact, cities seem to be particularly bad in that they entice high human capital people to move there and then die off, living their country worse than it was, though giving it a temporary boost in productivity. Cities used to be even worse than this, as due to infectious diseases and poor hygiene, they were very deadly to live in for most of history. To quote Greg Clark again (in A farewell to Alms, 2007):

Death rates were typically much higher in towns and cities than in the countryside. Urban mortality was indeed so high that, were it not for continual migration from the countryside, the cities would have faded from the earth. In London from 1580 to 1650, for example, there were only 0.87 births for every death. Without migration the population would have declined by a half percent every year.

Early towns were generally crowded and unsanitary, so that infectious diseases such as plague, typhus, dysentery, and smallpox spread quickly. Life expectancy at birth in London in the late eighteenth century, a mere 23 years, was thus lower than for most preindustrial societies, even though London then was perhaps the richest city in the world. As late as 1800 Londoners were not able to reproduce themselves: 30 percent of all infants died in the first year of life. Indeed urban dwellers in Roman Egypt had a better life expectancy than eighteenth-century Londoners.

The greater mortality rates of towns shows in the data from the English male testators, though there we have evidence only from smaller towns such as Bury St. Edmonds, Colchester, and Ipswich and not from London itself. While life expectancy at age 25 was 56 in the countryside, it was only 50 in the towns. And while 67 percent of children born in the country survived to appear in their fathers’ wills, in the towns it was only 64 percent. Surprisingly, though, the lower reproduction rate of those in the towns was due mainly to differences in fertility. The average testator in the countryside fathered 5.1 children, while the average town dweller fathered only 4.3.

…

The data also illustrate the well-known fact that in the preindustrial era cities such as London were deadly places in which the population could not reproduce itself and had to be constantly replenished by rural migrants. Nearly 60 percent of London testators left no son. Thus the craft, merchant, legal, and administrative classes of London were constantly restocked by socially mobile recruits from the countryside.

With that said, this post is about a new paper:

-

Finnemann, A., Huth, K., van der Maas, H., Borsboom, D., & Epskamp, S. (2023). The Urban Desirability Paradox: UK Urban-rural Differences in Well-being, Social, and Economic Satisfaction (No. 3g2d8). Center for Open Science.

As the majority of the global population resides in cities, it is imperative to understand urban well-being. While cities o er concentrated social and economic opportunities, the question arises whether these benefits translate to equitable levels of satisfaction in these domains. Utilizing a novel, robust, and objective measure of urbanicity on a sample of 156k UK residents, we find that urban living is associated with lower scores across seven dimensions of well-being, social satisfaction, and economic satisfaction. Additionally, these scores exhibit greater variability within urban areas, revealing increased inequality. Lastly, we identify optimal distances in the hinterlands of cities with the highest satisfaction and least variation. Our findings raise concern for the psychological well-being of urban residents and show the importance of non-linear methods in urban research.

They begin by summarizing the (alleged) causal benefits of cities:

Why are cities popular? Theories of urban agglomeration and urban scaling agree on an answer. Bringing people, companies, ideas, and technology in physical proximity generates synergies and with that tremendous wealth, innovation, creativity, and knowledge (4, 5, 6, 7). Across countries, a 10% increase in urbanization is correlated with a 61% rise in per capita GDP (8), and within countries, the world’s 23 mega cities exceed the country average GDP by 80% (9). Thus, urbanization has concentrated individuals and high-paying jobs in cities. Urban popularity can therefore be explained in terms of the “urban promise” of social and economic opportunities (10). A central question is whether cities live up to that promise. In other words, do urban opportunities translate into a psychological advantage of increased subjective well-being that one might expect? The frequently studied area of urban-rural differences in happiness suggests a negative answer (11, 12, 13). For economically developed countries, rural areas consistently show higher happiness. This urban disadvantage is termed “the rural happiness paradox” 1.

For the record, I will note that there are a few large cities that are actually poorer than the countryside due to low human capital immigration (Muslims and Africans), these being Brussels in Belgium and Berlin in Germany (which is still richer than surrounding East Germany, but poorer than West Germany). But that aside, the authors are right that cities are usually wealthier, especially the capitals.

The authors used a new, improved measure of urbanicity based on distances to population centers:

Their data comes from the ever relevant UK Biobank, which is presumably also why the authors are keen to talk about everything in terms of health and well-being. The UK Biobank is only available to researchers on the condition that:

The vetting process

Trained personnel carry out background checks on any researcher who applies for access. They review the researcher’s professional history and look for evidence that they have carried out high-quality health-related research. They must be working for a legitimate research organisation with a track record of health-related research. All researchers are checked against international sanctions lists.

Our in-house scientists then assess whether the research proposal qualifies as health-related research in the public interest. This means the findings should be likely to benefit the health and wellbeing of society, and should not cause harm, such as perpetuate stereotypes about certain groups.

If there is any doubt about this, or if the proposal raises any concerns, it is referred to UK Biobank’s expert Access Committee which will consider the application in more detail and seek ethics advice if needed.

All applications go through this process, regardless of whether the researcher works for a university, a charity or a company. UK Biobank has approved more 4500 applications, and rejected many others.

So if you want to use the UK Biobank to study something cool that isn’t strictly speaking health-related, you have to somehow frame it that way. The reason for this, I suspect, is that the money was gotten for this mega project by selling it to the health authorities (“something something, if we learn more about health and genetics, we can improve healthcare”). Most research funding comes from health research due to the public’s strong interest in this topic, and then gets diverted into whatever tangentially related matters that researchers really want to study. (So if you want to study ethnic gaps using UK Biobank, you have to frame it in a health way, say, how ‘White Supremacy’ harms Blacks BAMEs or some such).

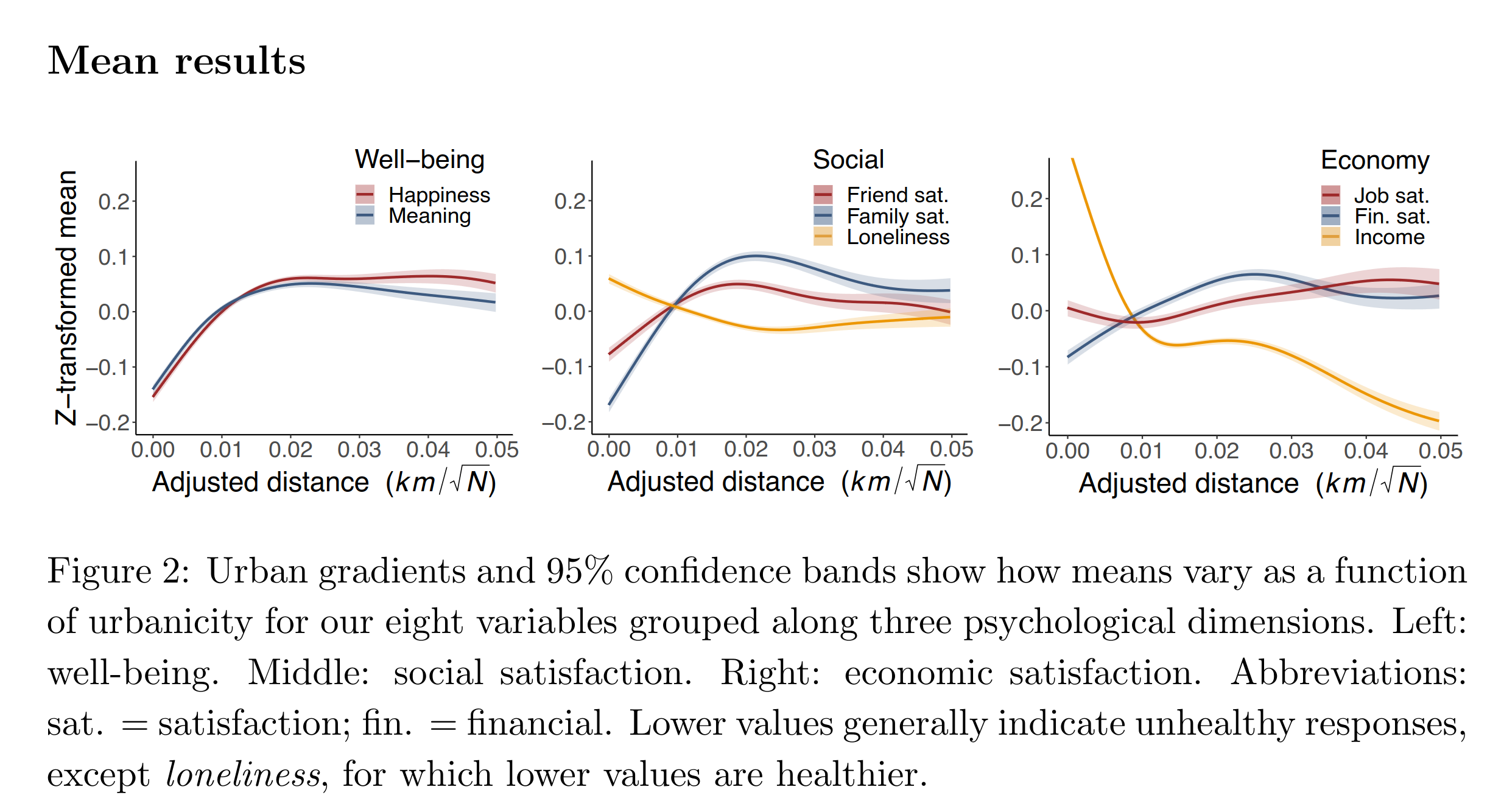

The main results look like this:

So how far do you really want to live away? Well, the plots show that a medium distance is best. You want to be far away from the decay and high density, but close enough you can get there if you need to attend a meeting, have fun, and get to your job. Notice in particular how incomes are higher closer to city centers, but people are actually less not more satisfied with their jobs and finances. This would suggest that prices increase more than incomes do.

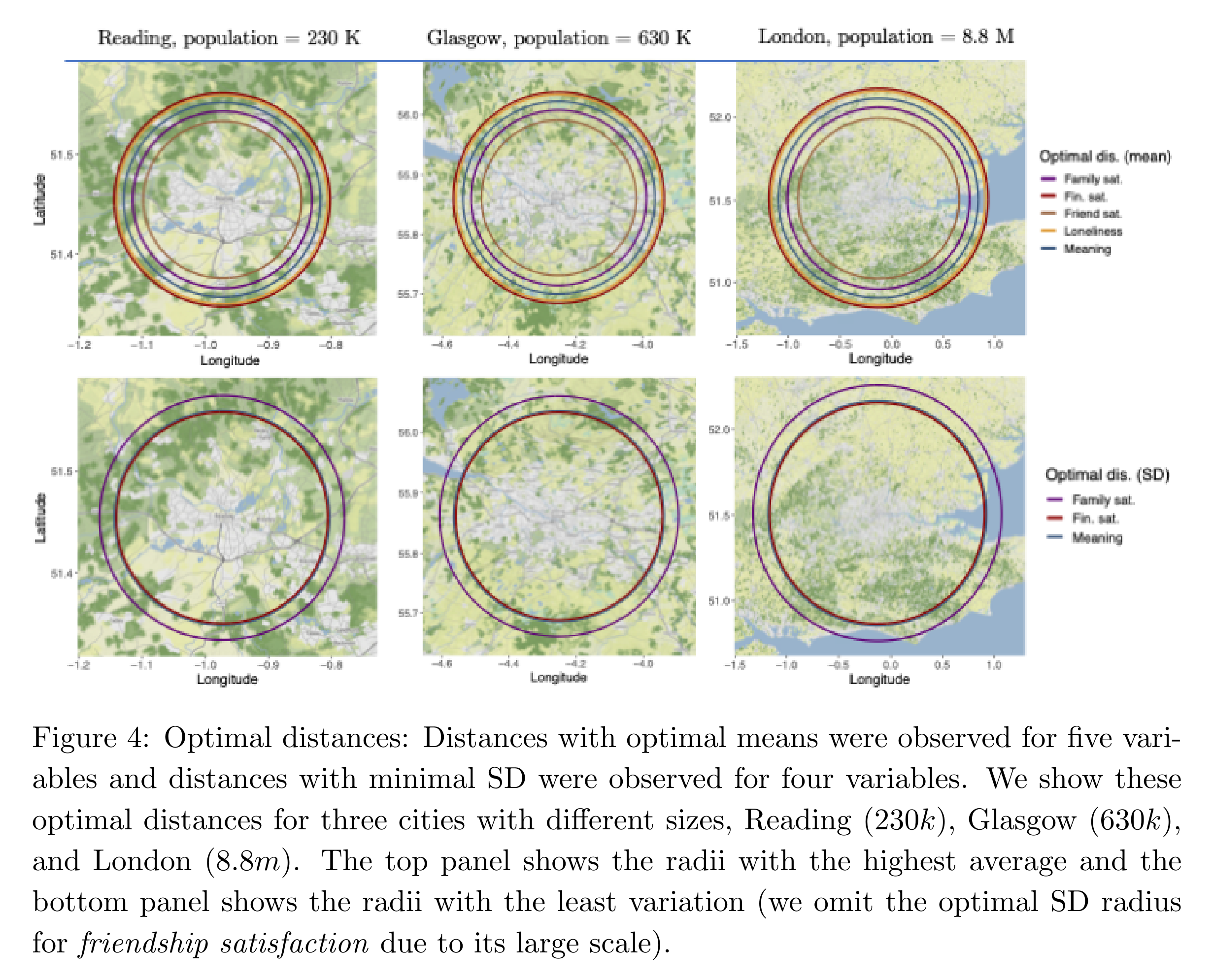

Since the figures aren’t entirely interpretable for normal humans (unless you want to pull out a calculator to figure out what the square root of a population size is), they provide nice maps too for the UK:

The top 3 maps show the optimal distance for maximizing your values for their outcome variables: family satisfaction, financial satisfaction, friend satisfaction, loneliness (reversed), and meaning in life. The circles aren’t exactly on top of each other, so you can pick somewhere in the middle of the circles for roughly optimal conditions across the board.

The bottom 3 maps show the optimal distances for minimizing diversity (the standard deviation) in these outcomes. The authors basically accept the communist ideal of less diversity = good — at least insofar as social circumstances is concerned (remember, more ethnic diversity = good). These distances are slightly further out than for optimizing for the mean values. I don’t think this should matter to normal people, but interesting nonetheless.

They do provide the distances in real units too, so if you are looking to live in London, you should instead be looking for a house about 65km away from the center. If you instead want to live in Glasglow (Scotland), the optimal distance is about 18km, and if you wanna settle for Reading, you only need to be about 10km away from the center.

Are we really sure these effects are causal? What about self-selection? Naturally, the authors leave this open in the usual causal language gambit:

We now address the study’s limitations. Our focus is on identifying robust trends in urban-rural disparities, not addressing the immensely complex question of explaining the underlying causes. Accordingly, our independent variable, “adjusted distance to city centers”, is not intended as an explanatory factor. The distance itself does not cause any changes in psychological satisfaction. Rather, distance is correlated with a host of urban processes such as accommodation type, sensory inputs, infrastructure, commuting time, job types, pace of life, educational access, cultural offerings, green spaces, living costs, etc. We leave it for future research to map the drivers of urban dissatisfaction. However, we need to make one theoretical remark to avoid confusion about implications. Our results do not imply that moving to cities makes anyone unhappy or that moving out makes anyone happy. This is because the observed patterns are both shaped by place-based factors and the systematic movements of psychologically resilient and vulnerable individuals (46). Thus, the observed optimal distances might arise from happy individuals choosing to move there rather than the locations themselves enhancing individual well-being. Disentangling the relative importance of place and selection effects is a central theoretical question for future research.

Selection bias is of course the main worry, as it is the main worry for all social science. Humans aren’t randomly allocated to their present situations or environments, broadly speaking, they move into them (or out of them!). However, since we know that human capital correlates positively with moving to cities, this selection bias would tend to be opposite of the observed associations, thus making them too small, not too large. Of course, we could posit that especially mentally unhealthy but high human capital people move to cities. Perhaps this is true to some extent, but I very much doubt it can explain everything we see here. Here a sibling study would be very interesting and it is possible in the sample they used as the UK Biobank has some 20k sibling pairs.

The main worry I had was whether the urban samples are just more non-European as the non-Europeans are usually worse off in these metrics. The authors don’t seem to have controlled for ethnicity in their model, but it can’t be too important because the UK Biobank is almost entirely European because it sampled old UK residents, and their subset was: “97% White, 0.7% Black, 1.1% Asian, and 0.6% other”. There can hardly be a large bias here remaining from cities being less European. There can however be a big problem with age, as the age range in the sample was 40 to 70, They included age as a control in the models so results are not just due to older people being happier and living further away. I don’t see if they looked for age interactions, i.e., whether the distance to city center effect depends on your own age. It would make sense if living closer to cities in the age before finding a spouse might relate to happiness a bit more positively than for older married couples. But it doesn’t appear they looked into this idea.

All in all, this is a great study. I do not recommend living in cities. But you might accuse me of bias since I grow up in the countryside. In fact, using their model, I can compute that my childhood home has an adjusted distance of about 0.05 (about 10k from urban center of 40k), a little too far away according to their modeling but still good. As to the question in the title, one might propose a gambit: you can move to cities, and you get a chance of getting a really good outcome, but on average, your expected outcome is a bit worse off. It’s like moving to Hollywood in search of an actress career. You have some chance, but more likely you will end up as a waitress or in porn.